“It is now ten years since we met, six years since we last spoke, four years since your death, and I’m writing you this from Mexico City. It’s not a letter, since I know you cannot reply. This is the chant recalling your life.” So begins Lauren John Joseph’s At Certain Points We Touch, immediately plunging the reader into the depths of grief while mapping out the course the novel will take. Over the following pages, the protagonist/narrator, JJ, traces out the contours of an epic, heart-wrenching love affair with Thomas James, a cheeky, headstrong photographer. JJ dedicates the text to the now-deceased Thomas, addressing him directly as they reflect on their tumultuous relationship. The two tragic lovers cease speaking, repair their relationship and then fall apart again. They share moments of love and affection, only for the darker, crueller parts of Thomas’s personality to bob to the surface, disrupting the protagonist’s hopes for a happy romance.

As the lovers argue, fuck and explore what it means to be in relation with one another, the reader is granted an intimate, emotional and often devastating look at a dysfunctional relationship. At the same time, we’re given the opportunity to see in detail the evolution of a young person into an adult. The sensitive, hopeful narrator is desperately seeking out their place in the world, and we accompany them as they bounce around cities, experiment in their art, make friends and begin to discover themselves.

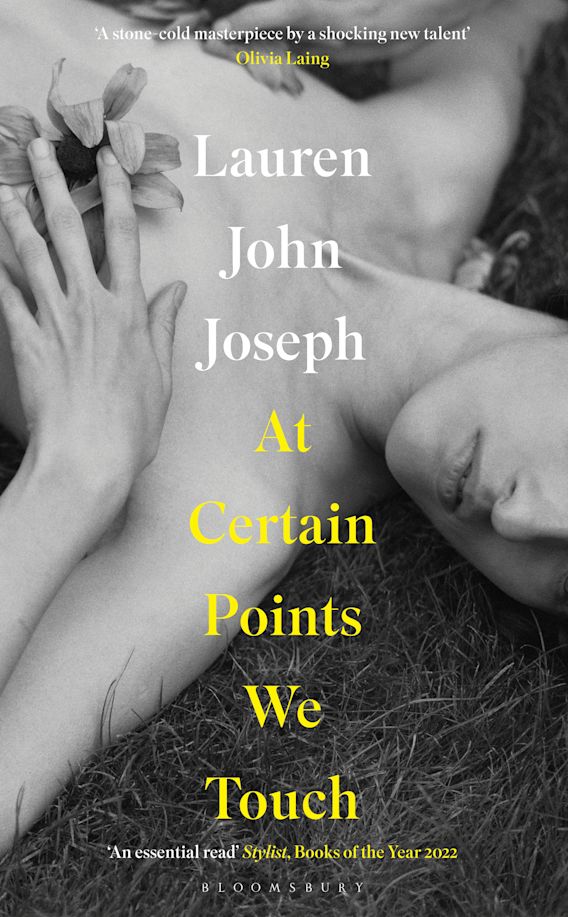

With their debut novel, English artist and performer Lauren John Joseph charts out a bildungsroman, a love story and an exploration of grief. It’s a bold, poetic interrogation of the questions that sit at the heart of what it means to be human: How do we love one another? How do we find our purpose? How do we grieve?

Known for their extravagant, fashionable performances and plays that explore sexuality and gender, Lauren John Joseph has presented her performances across the globe, from Tokyo to San Francisco. Fans will find much that resonates between their work on the stage and on the page—a sense of glamour and opulence, deeply thought interrogations of the self and the world, and a theatrical, nearly cinematic sensibility.

Lauren John Joseph spoke to Xtra about their new novel, getting stranded in Mexico after a breakup and the importance of moving beyond trans representation.

How much of At Certain Points We Touch was based on your personal experience?

The crucial incident, the death of Thomas James, was a real event. I really did lose someone close to me, in the same way that’s depicted in the book. But one sad story doesn’t make a novel, and I needed more than that. I wanted to write a book that contained the impact that his loss had for me, and I reverse-engineered everything else from there. One of the novelist’s tools is manipulation, and there’s a fair amount of that going on in the book—I manipulated reality so that the plot details and the people concerned are all fictitious. The protagonist’s backstory, however, is more autobiographical. I really did grow up in Liverpool, and I placed in things from my own life as I was spinning the story.

How would you describe At Certain Points They Touch as a work of fiction?

For me the book is fundamentally a love triangle, in which the three participants—the protagonist, Thomas James and the protagonist’s friend Adam, who becomes involved with Thomas—each have a different idea of what’s happening. I couldn’t understand why I wanted to write about a love triangle until after the book was finished. I realized that in my teens, my mother and her sister had both been in very compassionate love affairs with the same person. The fallout of this love affair totally destroyed my family, to the point where we had to leave town. I had never really processed that, so once I’d written the book, I was like, holy shit. I discovered that I’d written a book that tried to understand how people who love each other can be so awful to each other. I think I had a subconscious desire to talk about that affair, while I was writing about a totally different tragedy. I suppose you always think you’re writing about one thing, but you’re really writing about something else.

What’s interesting to you about reworking the personal into art, and what’s complicated about it?

I don’t think I’ve ever had much choice about reworking the past. I don’t know if anybody writes in a way that’s completely impersonal. Maybe there are some people who make art that’s inspired by quantum physics or something, but usually they’re doing it through a personal lens. My friend James Bridle is a tech writer, and his stuff can look like it’s only about radios and the internet. But there’s a very political and personal agenda going on as to why and how he’s investigating these things. Of course, in my case, it’s dangerous to work with the personal, because there are real people involved. Other people knew the actual person that the Thomas James character is based on, and they had to read this version of him. I let people know what I was doing and sent them advance copies, and I warned them that they might not be happy about it. But I’ve been very lucky because everyone’s response has been very positive.

Why did you want to explore your grief through writing?

Whichever way you explore your grief, it’s going to be difficult. There’s no getting away from that. Writing a novel is a good match for this task, because it’s very intimate, especially if you’re writing in second person. I use “you” throughout the novel, and while the book is ostensibly addressing the Thomas James character, the reader also feels like you’re talking to them. That brings about an intimacy which is very helpful when writing about grief. If you want to explore grief in very broad strokes, you can write something more like a self-help manual or a psychoanalytic assessment. But if you want to talk about personal grief, you’d want to use a more personal technology, and to me that means the novel.

You live in London, and much of the book is set in England, as well as in the United States. But the setting of Mexico City, where the narrator is recounting the story from, lingers in the background of the story. Why did you choose that location?

I wanted to write this book for a long time, but I kept thinking it was a tacky, exploitative thing to do. So it sat on the back burner; I thought it was too hot to touch. And then I took a trip to Mexico with a boyfriend who quickly became an ex-boyfriend. It was a really silly situation: I didn’t have a return ticket, I didn’t have any cash and I didn’t know anyone there. I was sitting in Mexico thinking “now what?” I needed something to do to stop myself from going off my rocker entirely, so I started writing. Mexico City left a really indelible imprint on the book. It’s just like Joan Didion says: “Novels are like paintings, the original strokes are still there in the texture of the thing.”

In what ways did Mexico City influence you and your writing?

There’s a certain historicism to the book, and that was definitely shaped by being in Mexico City. It’s a city where you’ll walk past a 16th-century convent that’s now a day spa, or you’ll find a Denny’s opposite a 2,000-year-old ruin. The expression of religiosity is everywhere. You’re confronted with a living spirituality, one that infiltrates every place you go rather than just being confined to Sunday mornings. There’s a constant sense that there’s more than just the physical reality, and that bleeds through into the book—there are many quotes from scripture, and explorations of Catholic theology.

What’s your personal relationship to religion or spirituality?

I actually grew up Catholic, and I’m still Catholic. I go to a Jesuit church in Mayfair in London, which is very progressive. We even have LGBTQ+ masses. The Jesuits are only answerable to the Pope, which means they can have these LGBTQ+ masses and do outreach to LGBTQ+ communities, whereas other churches can’t because they’re subject to the bishop and archbishops. It’s amazing, because the masses are in this enormous Victorian church, but it’s the equivalent of going to church on Fifth Avenue. The building is next door to a Celine boutique. It’s a very odd place to go to church.

The novel establishes parallels between coming into your artistic identity and coming into your gender or sexual identity. The protagonist explores both simultaneously. What’s similar about these things to you, and how do they influence each other?

To reveal yourself, you have to experiment a lot. That’s true for your personal identity and for your artistic career. I’ve tried many different mediums in my work: performance art, theatre, film, writing and more. I’ve also tried many different gender expressions. These things have definitely influenced one another. When I started making theatre pieces, that was the first time I had a space to compose a new identity, and I walked off the stage with that identity. As an artist, I spend time with people who are artists and not bankers. I get to meet people who are living less conventional lives, and that’s very inspiring. It makes me think that certain things, like gender and sexuality, aren’t that big of a deal. Maybe if you work in an office, it would be so much more of a big deal. But it’s easier when you don’t feel like you’re doing it all on your own.

The gender exploration of the protagonist, who is transfeminine, isn’t a focal point of the book at all. Why’s that?

I thought it was a more interesting story to tell. Earlier this year Morgan M. Page wrote an essay for her Substack called “After the Gimmick,” about At Certain Points We Touch and Shola von Reinhold’s novel Lote. She writes about how both these books have transgender protagonists, but that isn’t the story. Her thesis was that we’ve had the memoirs, we’ve had the books written for an audience who have no experience of what it means to be trans. At this point, we’re ready for books and movies where protagonists can be trans, but it’s not the linchpin of the story.

In terms of representational politics, if you have a character who is more than just their gender identity, that does flesh out and humanize people. I’m well aware that the majority of my readership isn’t trans people, it’s gone beyond that. I’m very happy that there are cisgender people who the book has resonated with for other reasons, whether it be that they’ve also had a loss in their life, or they had a very unpleasant relationship that they couldn’t extricate themselves from.

Were you thinking about representation while writing the novel?

I try to never think about anything like that. If I was thinking about representational politics, then I might try to shoehorn in other things that would make me seem like a better person, or I would strike a different moral tone. There’s a lot of moral ambiguity in this work, specifically with the Thomas James character being such a reprehensible person. I wanted to talk about the darker, muddier sections of queer life that are glossed over. There’s so much in queer culture that’s inherently racist or inherently transphobic. But that’s kind of glossed over when people write about their communities, either because they don’t notice it or because they don’t want to talk about it. It seems to me that if you’re going to truthfully represent queer lives, then it’s also necessary to bring those things to the front.

Especially as queer and trans readers, I feel like so much of our identity comes out of famous queer writers like renowned gay writer James Baldwin, the English modernist Virginia Woolf and New York novelist Andrew Holleran. These were writers who were deeply flawed themselves. But they’ve also shaped the perception of queer writing. I wanted to write a character like Thomas James, who was the embodiment of those flaws, so that we could see where that lineage has gotten us.

The book is peppered with cultural touchstones: references to other works of literature, art, music, religion and philosophy. Which works were most important to you while working on the book?

I was very much inspired by Edmund White’s Nocturnes for the King of Naples, a queer love novel. I found the tone of my book by reading it. I was also inspired by Olivia Laing’s Crudo, a novel that places the writer Kathy Acker in a contemporary setting. It’s the odd one out in her catalogue, as she usually writes art criticism. I was so excited that a writer with such an enormous readership would just go for it and do something different. I was also influenced by lots and lots of movies. I love that quote from American director Jim Jarmusch, where he says that life doesn’t have a plot, so why should books or movies? That really freed me up to not be too rigorous with the plot, to let it have a looping, cursive nature. I also watched movies from independent cinema trailblazer John Cassavetes, and from New German Cinema director Rainer Werner Fassbinder. I feel like there’s something cinematic about At Certain Points We Touch, and that aspect comes from my endless movie watching.

What do you like to do outside of your work?

I like to watch a lot of movies and read a lot of books. I’m a nature person, and I love taking walks out in nature. I’m also a big fan of dinner parties, and host them all the time.

What’s next for you?

I’m writing a new book, so that’s taking up a lot of my time. It’s about someone who moves to Berlin and then gets a lot more than they bargained for. I’m also considering working on a new performance piece. I had to stop performing because of the pandemic, so it might be time to get back into that.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra