The phrase “Be Gay, Do Crime” is such a current mood that there are actually two books with that title coming out this year. One of these, published by PM Press, is Be Gay, Do Crime: Everyday Acts of Queer Resistance and Rebellion. It offers a historical and sociological overview of queer rebellion and uprising, from the life and work of anarchist revolutionary Emma Goldman to Stonewall to the first Toronto Trans March in 2009, and beyond. Meanwhile, Molly Llewellyn and Kristel Buckley’s anthology, Be Gay, Do Crime: Sixteen Stories of Queer Chaos, is a collection of fiction rather than a historical summing up, and is more concerned with individual acts of gay transgression than with political disobedience and resistance.

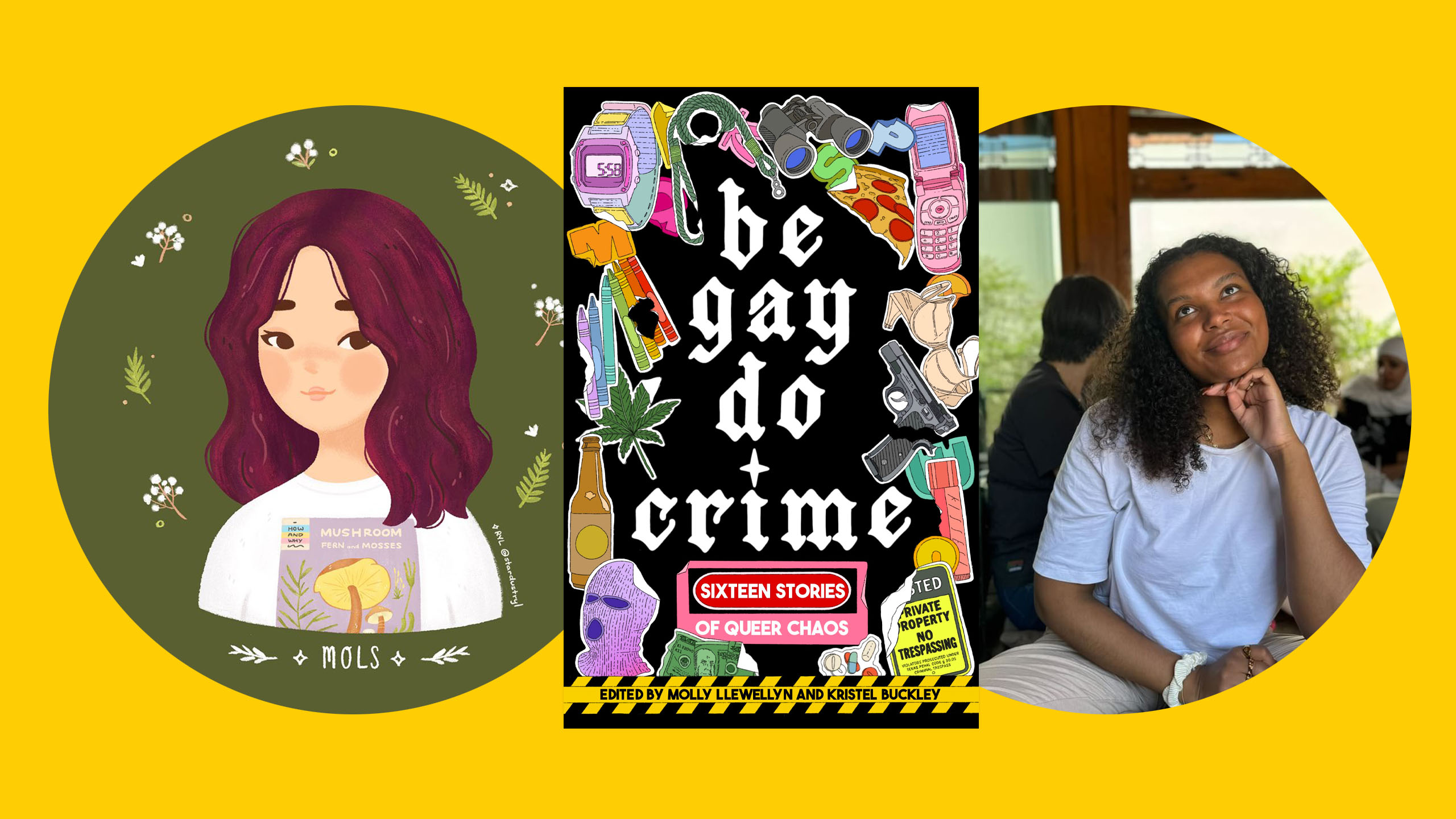

This is Llewellyn and Buckley’s second anthology; their first, Peach Pit: Sixteen Stories of Unsavory Women focuses on “fierce and dangerous” women. In the same vein, Be Gay, Do Crime centres stories about queer and trans people who break the law in various and highly creative ways. The anthology features a dazzling contributor list, including Venita Blackburn (Dead in Long Beach, California; How to Wrestle a Girl; Black Jesus and Other Superheroes), francesca ekwuyasi (Butter Honey Pig Bread), Priya Guns (Your Driver Is Waiting), Myriam Gurba (Creep, Mean), Aurora Mattia (Unsex Me Here, The Fifth Wound), and Kayla Kumari Upadhyaya, managing editor of Autostraddle. The stories oscillate wildly between funny, tragic, horny, delusional, cursed and freeing. I often expect anthologies to contain some filler, a necessary reality when editors are making sure to recruit writers across a wide range of experience, but this one is all killer—sometimes literally.

Though political disobedience is not the focus of most of these stories of queer criminality, the material conditions that lead to political dissent are present across many of these tales. The characters in these pieces are often living in subpar housing situations, feeling stressed and anxious about crumbling buildings and neglectful landlords, fighting with their roommates and partners in cramped quarters, and weathering the constraints of lockdowns and economic crises. They work dead-end jobs and despair at saving up enough money to access gender-affirming surgeries or start families or make down payments on houses. They bear the rejection of queerphobic and transphobic families and covet the seemingly easy lives of richer, more normative people than themselves. They grit their teeth through racism, institutional and interpersonal, and long for “fuck you money”—a term used in ekwuyasi’s story of the same name to describe an amount of funds impressive enough that it will shut up the racists and haters around you.

The stories in Be Gay, Do Crime bring us from London to Los Angeles; Vancouver to Washington, D.C.; Miami to the Arizona desert. The crimes chronicled in these pages include the mild (weed-dealing, pickpocketing, shoplifting, voyeurism), the more serious (blackmail, stealing a dog, stealing a baby, bank robbery, political assassination) and the zany (impersonating a child in order to win children’s drawing contests, pelting MAGA protestors with rotten beer hops, stealing a billionaire’s experimental anti-dysphoria drug). In Blackburn’s masterful piece of microfiction, “Black Jesus,” the main character’s transgression is spiritual rather than material. A young girl uses Wite-Out to erase the ten commandments in her grandmother’s Bible in order to write in her own, which are more relevant to her life, such as “Thou shalt not drip milk on the carpet.”

The crimes featured in these stories are often born of frustration or resentment, and don’t, with some exceptions, actively harm other people. We aren’t in the realms of Dennis Cooper or Gary Indiana here—there are no snuff films featuring underage characters (real or imagined) or gay serial killers within these pages, or even much that could be deemed smutty. However, many of the characters in Be Gay, Do Crime do get horny when they transgress, with crime becoming an erotic act in and of itself. In the opening story, Myriam Lacroix’s whimsical “The Meaning of Life,” a scrappy queer couple finds a baby abandoned in an alley and takes it home to raise as their own rather than trying to find its parents. Eventually the baby’s mother, struggling in her own life, starts stalking them, which leads to at first frightening then unexpected results. The two main characters feel justified in kidnapping the baby, having decided that “nuclear families were a concept made up by the same people who wanted you to get full-time jobs or sell your art for money.” Evading the baby’s mother, whom they judge for having abandoned her child in the first place, gives the couple a surge of horniness. They start having sex all the time, once they’ve put the baby to sleep: “They loved breaking the rules in the name of their love, and they especially liked getting away with it.”

In Alissa Nutting’s deliciously nasty “Peep Show,” a woman who works at an AI startup run by a skeezy man becomes convinced that his dog, which she has stolen, is actually a surveillance robot. She begins purposefully having sex with her girlfriend in front of the dog/robot, believing that the (possible) footage is responsible for the raises she has started to obtain. In one scene, after she has revealed the dog theft to her appalled girlfriend, the narrator asks, “But do you find the new criminal me a little sexy?” Her girlfriend doesn’t answer but they do proceed to have sex, pouring the boss’s expensive champagne, taken from an office party, all over their bodies. In Temim Fruchter’s haunting yet hilarious “Redistribution,” the protagonist, weary of her own dissatisfying life, breaks into the mansion of a famous writer who lives in her neighbourhood. In a scene reminiscent of Kristen Stewart’s character in the film Personal Shopper, the intruder makes herself very comfortable in the writer’s home, and among her things; she eventually gets naked in her bed and masturbates.

Many of the crimes in the anthology are committed from a place of queer anger or despair. In SJ Sindu’s “Wild Ale,” one of the collection’s standouts, a lesbian couple is constantly at odds during the pandemic lockdowns. Without any personal space, they are increasingly unable to connect. Outside their cramped apartment, anti-lockdown protestors wearing MAGA hats rally. The depressed partner is a university lecturer who is teaching a critical theory class online, focusing on autotelic violence—“violence for the sake of violence.” The couple rails at the selfishness of the protestors, “shouting at the world for daring to put the health of others before their own small freedoms” like haircuts, BBQs and prom. In the final scene, the couple manages to reconnect by exercising a little “violence for the sake of violence” of their own. The result is satisfying and emotional, even if their continued coupledom is not necessarily a given.

There aren’t many examples of collective criminality in the anthology, but Sam Cohen’s exhilarating, expansive story of queer bank robbery, “Operation Hyacinth,” is a highlight of the book. A group of mostly Mexican-American queers and trans people in Los Angeles are trying to save their collective housing complex from predatory developers after their landlady, Doña Carmen, dies. They carry out a two-pronged attempt to secure a stable home for themselves: one collective member, Pearl, communes with Doña Carmen’s spirit, encouraging her to haunt her daughter, who has the power to stop the sale of the property; at the same time, the group carries out a slew of bank robberies in small towns across the country, in a bid to collect enough funds to put a down payment on the complex. Their methodology is deeply queer: some of the transmasculine members of the crew don girl drag, sashaying up to the tellers and passing them notes that say they are armed and to give them all the money they have. After the robberies, they drive away in their getaway car, laughing and clapping: “We had felt so low-power forever, we realized, so take-what-we-can-get but now we were taking what we were due.” Eventually, dysphoria catches up with Cohen’s bank-robbing freewheelers, as do the realities of securing a mortgage as a bunch of ragtag queers, but the sense of collective queer and trans power that the story projects is energizing nonetheless.

Nobody gets through these stories without aftershocks and side effects. Yet each writer in Be Gay, Do Crime shows that acts of queer lawlessness are often necessary and justified—sometimes for personal survival, and sometimes for a much-needed moment of unfettered joy and freedom. After the couple in “Wild Ale” engage in their shared act of vengeance against the anti-lockdown protestors, the narrator remains aware that her relationship is not healed. But just for a moment, she looks at her wife, really looks at her, and sees that “her face is alive and wild with something I haven’t seen in her in a long time.” This anthology reminds us, through anger, delight, horniness and rebellion, that we can’t let queerness be tamed by unjust laws, social conventions and institutions. Breaking the rules might be what we need in order to thrive.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra