When I was living in Toronto and newly single, one of the first people I went on a date with was a physiotherapy student named Olivia. She had curly brown hair that always fell perfectly, like a doll’s. We met at a bar in the Gay Village with shitty cocktails and good sandwiches.

Olivia was one of the few women I’d matched with on the apps. I could lie and say that this was because of scarcity—pretend that, in all of Toronto, there simply weren’t enough queer women to go around. This is what I did sometimes when people asked why, after a life of mostly dating women, I was suddenly gravitating towards men. I just can’t find any queer people who are quite my type, I’d say. It’s just easier to meet men here. The truth is that dating women felt more complicated than it used to.

Olivia walked me home after our date, and said yes when I asked if I could kiss her. I had fun tonight, she texted me a few minutes later. I smiled down at my phone when I read the message, feeling the early flutters of a crush.

We met again the following week at an art gallery, where I showed her my favourite place in the whole city: the room in the basement full of model ships. It was always dark and quiet, with a golden light cast on each ship as though they were rare jewels. The ships varied in age and size and origin, and all had vague plaques about their histories. Revenge. Built in 1876. Destroyed by fire in 1877.

“I love this one,” she said, pointing to a tiny battleship with sails the size of a thumbnail. It was a good choice.

Afterwards, we went for brunch at a fifties-style diner with an hour-long wait for a table. As we stood in the doorway, we talked about travel to pass the time. She wanted to go back to the west coast soon, where her family was. I wanted to go to Malta, someday, where my father was born.

I liked Olivia, and I wish I could better remember the specifics of our conversations. What I know is that she laughed freely and often, her nose wrinkling and displacing the freckles on her cheeks. She spoke about physiotherapy, and how excited she was to help people with chronic pain. This was a good sign. She might be patient with me, I thought.

I mentioned my pain to her, which was at its absolute worst then—I could barely type at all, couldn’t button a shirt without cringing. She said she hadn’t learned about thoracic outlet syndrome in school yet, but she still seemed to understand when I explained it; when I pressed my fingers into the space under her collarbone and said here—this is where the nerves are caught.

On our third date, I went over to her apartment. She made me dinner, a pasta dish with feta and fresh basil she’d clipped from the plant on her windowsill. Afterwards, we chatted on the couch for hours. It was one of those conversations about nothing in particular, loaded with the possibility of what might come afterwards.

She kissed me very gently. On my lips, my cheek, my neck. And when we stumbled from the couch and into her bedroom, onto her bed, I started mentally practising all the ways I might say I’m sorry, I can’t. Later, when that moment came, I pushed past it, unable to let the words out. I’m sorry, I can’t. It hurts. I ignored it until I couldn’t move my fingers anymore; until the strain in my neck hurt so badly it was dizzying. I stopped suddenly and felt her body stiffen, her legs close slightly.

“I’m sorry,” I said quietly. “I can’t. My hands—my neck.”

“Oh,” she said. I could hear the trace of disappointment in her voice that I’d been dreading, and the chipperness with which she immediately tried to cover it. “That’s okay. Come here.” She softened, pulled me towards her, and kissed me lightly on the temple. “That’s fine,” she said. “It was nice.”

“Yeah.” I felt like I was going to be sick. I imagined getting home and disappearing—deleting her number, deleting the app we’d met on, crawling into bed and staying there for a long time. I blinked hard, trying not to cry.

After a few minutes, Olivia sat up quickly and said she had something for me. I watched her walk naked towards the kitchen and return with a bag of miniature mint-flavoured chocolate bars, which I’d mentioned were my favourite when we first met.

“For you,” she said. She kissed me on the cheek.

She asked me to stay the night. I didn’t. When I finally got into my own bed, exhausted and weepy, the pain in my upper body was so bad I couldn’t sleep. Olivia texted me that she’d had a nice time.

Olivia and I went on just a few more dates. We quickly realized we were looking for different things: she wanted a serious relationship, and I was too scattered to commit to anything. The bigger problem, though I didn’t say this, was that I was scared to have sex with her again. I was worried about the disappointment that might follow, remembering the way she’d stiffened when I’d had to stop. She was sweet and patient, and I knew she would have been willing to find solutions. I wasn’t, though. After our last date she walked me home and squeezed my hand.

“This has been really fun,” she said.

“It has been.”

We hugged, waved, and promised to keep in touch, though we both knew we wouldn’t.

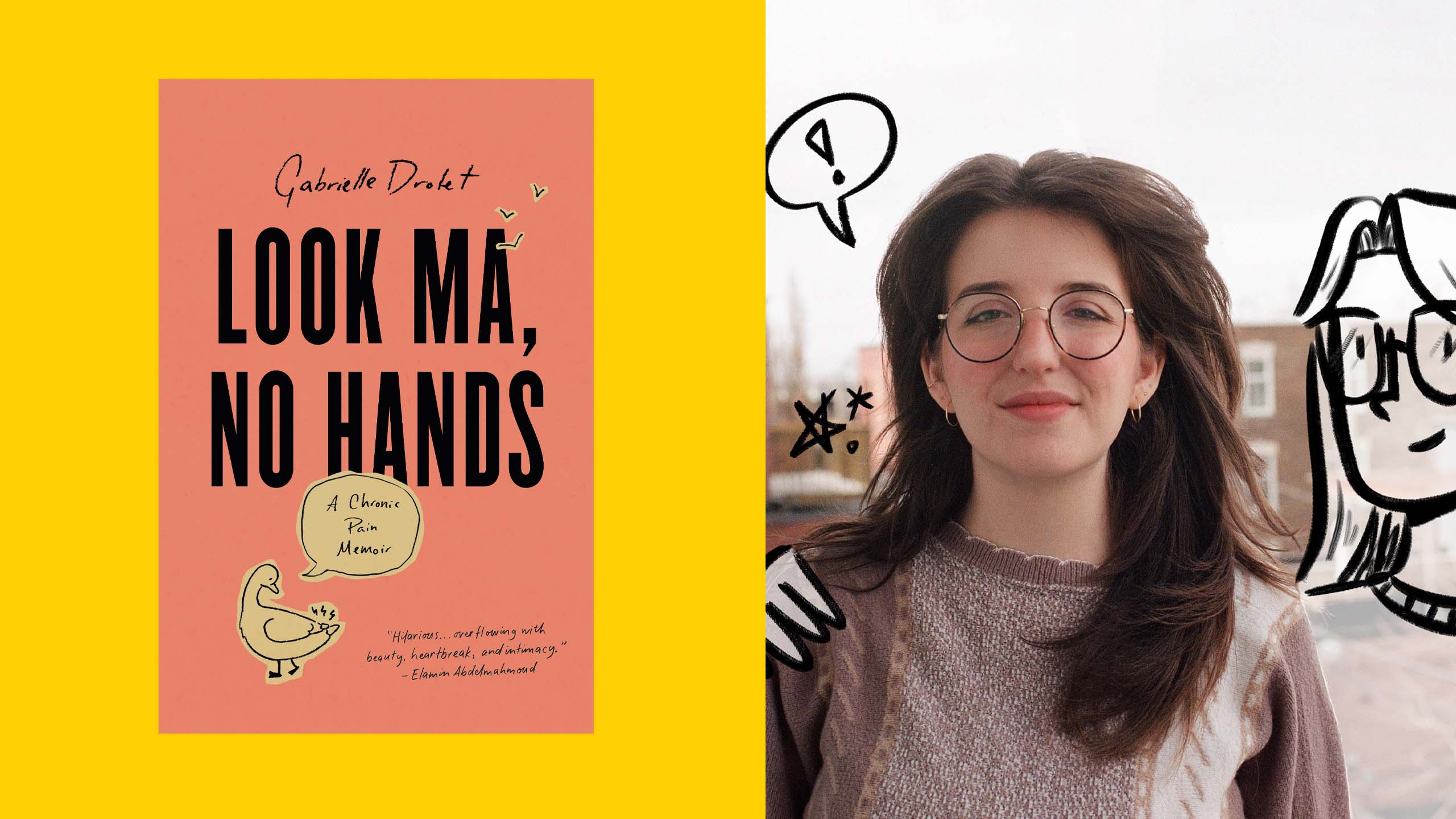

Excerpted with permission from Look Ma, No Hands: A Chronic Pain Memoir by Gabrielle Drolet. ©2025 Gabrielle Drolet. Published by Penguin Random House Canada www.penguinrandomhouse.ca

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra