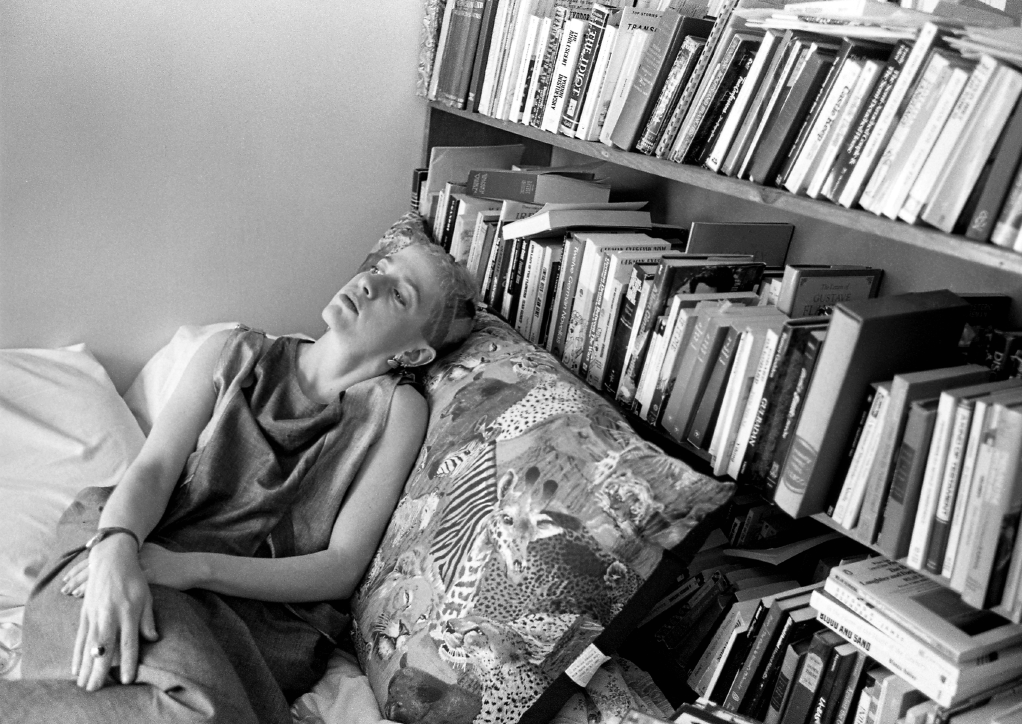

Kathy Acker was a rare kind of writer. With her unrepentantly experimental approach, scandalous subject matter and larger-than-life personality, she stands out as a peculiar figure in America’s literary landscape. Her books confused and shocked audiences for both their form and content, filled with brazenly controversial depictions of sexuality, and spliced together by lifting quotes and plot lines from other media, in an approach Acker cheekily referred to as “plagiarism,” to the consternation of her publishers. For issues related to both morality and copyright law, her work was frequently the target of harsh criticism, attempted censorship and, on the other side of the equation, cult idolization. Her personality similarly divided and intrigued—intensely driven, compelling and self-centred, Acker was as contradictory and multifaceted as her writing. In the late 1980s, she began to rise to a position as a kind of celebrity writer, her huge personality outshining the work itself, which never sold particularly well during her lifetime.

Despite this renown, Acker has never been treated to a full-scale accounting of her life and work. With his first book, Eat Your Mind: The Radical Life and Work of Kathy Acker, Toronto-based journalist and culture writer Jason McBride attempts to straighten out the tangles of Acker’s self-mythologized history. The result is a biography that illuminates a picture of a passionate, complicated and wounded artist, a picture that can be used to glean profound truths about the world around the artist: “Acker’s own life had its specific dramas, its unique twists and turns, but it also illuminated certain general aspects of sexual politics, the tyranny of the nuclear family, the blind spots of culture, and the slipperiness of subjectivity,” writes McBride of the task of Eat Your Mind.

Though Acker’s books repeatedly used material from her actual experiences, this tended to complicate the picture of her life more than reveal it. From Empire of the Senseless, a dystopian epic about a pirate and a cyborg, to Blood and Guts in High School, a disturbing and dreamlike story about a young girl who suffers a number of calamities, Acker paged in details of her life in a sensational way, mixed in with fiction, imagination, theory and other writers’ works. Acker was able to write about and work through the personal while simultaneously pulling a veil over her life, for readers and acquaintances alike. Her whole career was spent playing with notions of identity, memory and history; in earlier works she even used playful pseudonyms like “Rip-Off Red” or “The Black Tarantula,” attributing manuscripts to these alternate personas. This self-mythologization makes it a daunting task to piece together the actual facts of Acker’s life. The task is complicated even further by the extremely varied ways other people experienced her—and by her penchant for lies and exaggerations.

Eat Your Mind functions a bit like the parable of the elephant—McBride weaves together interviews or correspondences with dozens and dozens of people from Acker’s life, presenting readers with numerous different diverging perspectives on her. Acker is, to those around her, by turns friendly and standoffish, insecure and narcissistic, wounded and cold-hearted. What’s clear through all these accounts McBride has gathered is the intense influence that Acker had on those around her. She moved through rooms and lives like a whirlwind, capturing the hearts and minds of her innumerable contemporaries, friends and lovers. The diversity of sources included in McBride’s book illustrate the rich and varied nature of Acker’s life—her circles included celebrities as varied as famed comic book creator Alan Moore, non-binary poet Eileen Myles, famously imperilled literary legend Salman Rushdie, literary punk Dennis Cooper and avant-garde writer Bernadette Mayer.

It’s impossible to adequately write about Acker as a person without also writing about the cultural scenes she was a part of, movements that she influenced while they influenced her. For Acker, being a writer wasn’t simply a vocation, it was her whole life; when she wasn’t working on a book, she was networking her way through the art and literary worlds. By writing about Acker in the cities she bounced amongst—mainly New York, London, San Francisco and San Diego—McBride biographies not only Acker, but also the artistic and academic undergrounds of the ’80s and ’90s. Acker’s work was more explicitly referential and social than most, pulling from sources as diverse as pulp novels and the theory of French philosopher Gilles Deleuze, and her lifestyle reflected that. She hung out with psychics and leather dykes, film critics and poets, and was a part of various significant cultural movements that included New Narrative writing, Language poetry and postmodern theory.

“She was never that interested in women. She tended to view them as competitors in her frequently obsessive pursuit of men.”

In San Francisco, Acker was an idol in the city’s queer and hard-core communities, an important part of queer literary circles during a time of intense change and cultural activity. She could often be encountered eating at Zuni Café, known as the gayest restaurant in the city: “It became Acker’s favourite restaurant, where she would feed dinner to a blindfolded McKenzie Wark,” the philosopher with whom Acker briefly had an obsessive, kinky relationship. For these reasons and others—her affinity for leather and kink, her shaved head, her obsessive bodybuilding and motorcycle riding—Acker is often seen as a part of queer literary history. She, too, perceived herself as a part of a trajectory of queer writers like Jean Genet, the subversive French writer and dramatist, and William Burroughs, the experimental American beat writer, both of whom influenced her work. In her writing, like in her life, she often played with and subverted gender—gender-bending her characters, switching around their pronouns in disorienting ways.

Eat Your Mind complicates our understanding of Acker’s queerness. Interviews with those close to her reveal that, though Acker felt an affinity with and at times aligned herself with queer culture, and with lesbians specifically, she was never that interested in women and didn’t pursue relationships with them. She tended to view them as competitors in her frequently obsessive pursuit of men. “I’m so queer I’m not even gay,” as Acker herself put it, a statement that skillfully captures her ability to be at once offensive, intriguing and hilarious.

Though written with palpable affection, Eat Your Mind doesn’t shy away from casting light on Acker’s darker sides. The strong personality and blazing life force that carved a place for her in literary history resulted, time and again, in chaotic and hurtful relationships with people. As Cooper tells McBride, “All of my writer friends in New York knew Kathy but had incredibly difficult relationships with her.” The American artist Constance DeJong recalls Acker, at the time a close friend, switching up on her without warning, to her shock. In the press release for a joint reading, DeJong was listed as performing after Acker, but “just before the event was to start, Acker took DeJong aside. ‘I’ll just tell you that you don’t want to go second, because what I’m doing is so amazing, you cannot follow.’” With her insecurities, burning jealousies and cutthroat ruthlessness, Acker’s relationships were more often than not characterized by drama and pain, especially the romantic ones. Her endless capacity for making friends made it so there would always be replacements for the relationships she would unceremoniously end for some unspoken grudge or perceived slight. “You were always Kathy’s friend; she was never your friend,” recalls author Lynne Tillman.

“I’ll just tell you that you don’t want to go second, because what I’m doing is so amazing, you cannot follow.”

McBride nudges the reader toward recognizing Acker’s hurtful behaviours as rising out of the deep wounds in her life, wounds that also formed the foundation of her writing—her tumultuous and painful childhood, the abuse she endured from her mother, her abandonment by her birth father before she was born and later, the suicide of her mother. Acker endlessly explored her abandonment and abuse in her work, reworking the themes and details into nearly all of her books in some way or another. By reimagining her pain as a creative force, Acker was able to wrest control of her life’s narrative, granting herself an agency invaluable for moving on from trauma. For her novel Great Expectations, modelled off of the Charles Dickens classic, “Acker chose [the Dickens book] as her starting point ‘for emotional reasons.’ It was a book she loved as a child. Writing in part about her painful childhood, she wanted to ‘destroy this book I absolutely loved,’ and, ergo, destroy her childhood,” writes McBride.

Rather than limiting Acker to a singular version of herself, like the “traumatized Acker,” Eat Your Mind presents a number of different Ackers in chorus with each other, illustrating her rich multiplicity with often outrageous anecdotes. In one scene, Acker laments her supposed poverty while “accidentally” dropping a large wad of cash out of her purse. In another, she brings British writer Neil Gaiman—a platonic acquaintance of hers—back to her apartment and drunkenly begs him to whip her directly in the pussy, which he reluctantly does. She sends an irony-laden letter to Susan Sontag asking if she would please make Acker famous—“Dear Susan Sontag, would you please read my books and make me famous? Actually I don’t want to be famous because then all these people who are very boring will stop me on the street and bother me.” She’s arrested by a vice squad while performing live sex with her boyfriend at a New York peep show theatre called Fun City. She gets her genitals pierced after watching the trans noise musician Genesis P-Orridge doing the same onstage during a show.

Through all the anecdotes and interviews, Kathy Acker shines through as a passionate, scandalous and larger-than-life figure—a true rockstar writer.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra