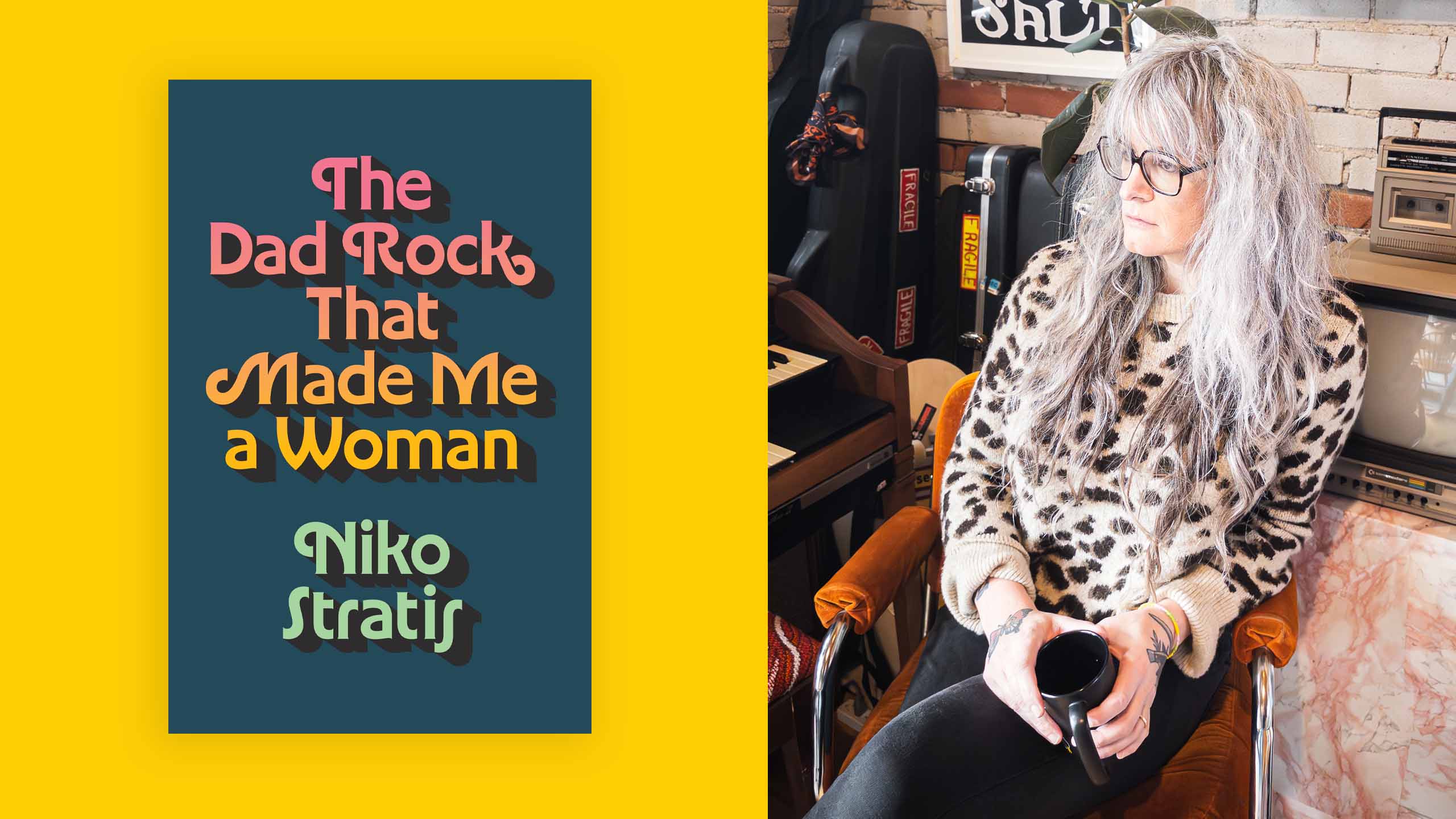

Having made her way from journeyman glazier to beloved music writer, with a gender transition in the middle, Niko Stratis has a story to tell. In her debut memoir-in-essays, The Dad Rock That Made Me a Woman, Stratis creates a mixtape (literally, each chapter is a song title) of reflections on family, music, substance abuse and—above all—survival. Stratis begins with a story of listening to the Waterboys in her dad’s truck, but throughout the book we see how, in addition to her relationship to her father, many other things shaped her: work colleagues, partners, the melancholy of the Yukon and particular song lyrics that got her from booze in a bathtub to where she is now. What makes real dad rock, for Stratis, is less about what a male parent listened to and more about the soundtrack to transformative moments in life. Dad rock is the music that rears us, the music that helps us figure ourselves out. In Stratis’s life, that included everything from Bruce Springsteen to HAIM, Sheryl Crow to the National, and R.E.M. to Neko Case. Stratis’s writing is as lyrical and potent as the songs she writes about; in that sense, the book is a master class in form mirroring content.

It will bother some that her transition doesn’t really appear until late in the book (Stratis tells me that’s already been mentioned by some early readers), but as a later-in-life queer myself, I loved getting to read about the complexity that made her who she is, even if it’s not a pat narrative. This is the core of Stratis’s work: she reflects on the stuff of life that is messy and complicated, and—like our favourite musicians—she makes art of it.

I want to talk about definitions and the queer practice of exploding them. We have a lot of norms in society around gender, parenting, and also … what counts as dad rock. I think your book illuminates the absurdity of rigid definitions. Would you speak to this aspect of the book?

I saw people reacting to the title and talking about bands that I had no intention of talking about. When I first announced the book, a lot of people started asking me about Steely Dan.

And I was like, “I’m never going to talk about Steely Dan.” I wanted to solve this idea of, like, “What makes a dad?” and how can I divorce that from gender and even from familial obligation. I was thinking of the Replacements in particular, who show up in the book with the line, “He might be a father but he sure ain’t a dad.” And I was trying to break that down and be, like, “Well, so what does a dad really mean, then? And what is it we are talking about when we talk about dad rock?”

I had the title before I put the idea of the book together. The title was funny to me. And then I started putting it together and challenging myself based on that to be like, “Well, if I think dad rock is an absurd genre, how can I kick the doors open on it?” And that’s when I started asking myself: “Can women be dad rock? Can queer people be dad rock? Can people that don’t have children be dad rock?” And ultimately I landed on “yes” for reasons that I sort of defined for myself and then went looking for artists that fit the definition that I created.

I had somebody write me and say, ”Well, you know, my dad didn’t listen to music.” And I’m like, “But you didn’t just have the one dad necessarily. Like, if you had other people that raised you who were informative or who imprinted upon you in some way. And if music was a part of them, then that’s dad rock too.” It is whoever guided you to the place you find yourself now—that is the more important thing to me. And that was sort of part of that definition was like, “Well, who built the boat that got you here?”

A lot of the music in the book is music you remember from different jobs. Can you talk about why “work music” is so potent for you in your recollections?

I grew up isolated in a very rural and extremely working-class blue-collar family. My dad is a tradesperson. My mom hasn’t worked for a long time, but she worked odd jobs when she could and she just hasn’t been able to work a job because of her health for a long time. I got my first job when I was 13, and I’ve worked pretty much every day of my life since. I’m 42 now, so that’s a long time.

Work was a very integral part of my life. So I built a lot of memories around that. When I started my career as a writer after being a trades worker for so long, I had a lot of hang-ups about my lack of education. I went to talk to a classroom of MFA students and I always joke about my lack of education. Lately, I’ve been trying to train myself out of it because I think it not only does me a disservice, but it also does my dad a disservice. My dad, who also doesn’t have an education, who still works in trades and is a very smart, very compassionate and very educated man in his own way.

I think that people struggle to write about work because we’re told this grander idea of, “No one dreams of labour.” Like, yes, it’s true. But for some of us, it’s all we have—you know? I never had parents that helped me get into a college or helped finance my way into my career or any of those things. I had to work my own way to get here. And I think it’s important to honour the work that got me here. My time as a physical labourer and even the jobs I had before that, all of those experiences inform who I am.

You write a lot about violent performances of masculinity that you experienced and felt coerced into performing. You also have beautiful counter-examples,and we eventually get to read about you freeing yourself from that coercion through transitioning. I’m not asking you to solve the manosphere problem, but since you’ve given masculinity so much thought from a critical perspective, I wonder if you could talk about what you’re observing about masculinity today.

I write about masculinity a lot because I lived with it for a long time. You know, I transitioned in my 30s, so I existed in that space for a long time in my life and definitely had it enforced upon me and I absorbed a lot of bad lessons and I acted poorly for a long time because of it. It’s like a performance that kind of took over my life in its own weird way, and it was destructive for a thousand reasons.

When I see men that are able to be emotionally vulnerable with each other in public, I think that is a really welcome change.

But I also think that it’s easy for men to fall into toxic spaces because they feel like they’re owed something, and when they aren’t getting a treat for whatever behaviour they think earns them one, it’s easy to fall in with a sort of right-wing crowd that is promising a lot of rewards for being bad people.

Men don’t have to think about community a lot, right? Because every community they feel belongs to them. And I think that is a damaging thing. Men need to start to consider the spaces that they’re in a lot more and be thinking, “Whose community is this and how do I honour that; how do I help preserve it; how do I help look after it in a way that doesn’t centre me?”

I think a thing that would help men is … look, all men should just transition. [both laugh]. There is always that idea of, like, “How do we solve the male loneliness problem?” Like, I don’t know. That’s their problem. Listen to more Gordon Lightfoot and tell your friends you love them.

You write about Canada with a lot of reverence, even when you have complicated feelings about the places you’ve lived. Can you talk a bit more about how you see a connection between music and place?

I grew up in the Yukon, a place that a lot of people don’t know about. And when people talk about the Yukon, they use it as a shorthand for “the middle of nowhere.” And so I really wanted to take the spirit of what John K. Samson does so well with the Weakerthans, and be like, “How do I make places feel real even when maybe they weren’t always the best?” And I think the Yukon is a very beautiful place. So I wanted to write lovingly about it.

At the same time, the more I was listening to music and researching and thinking, I started wondering about where the musicians were from. When I’m writing [about the Yukon], I really like trying to make places feel alive because I want to put people in places they might never go. A backdrop always feels important to the story being told. I think it’s a thing that music always does really well; really beautiful emotive songs will often create a space.

The crux of the book is how music got you through addiction, recovery and transitioning. You’re clearly demonstrating how powerful a tool music is in creating and supporting change. But the music in your book is not protest music or “message” music. I’d love to hear your thoughts on the role of music, if it has one at all, in addressing this moment of intense transphobia, ecocide, genocide, economic turmoil, etc.?

You know, I think a lot of protest music is bad. I hate to say it, but especially now the messages are really pointed. And I think losing the poetic nature of a song really kind of kills it for me. We see the broad scope of a lot of issues right now. And I think the work that art kind of does is humanize [those issues], and humanize the people within them. You can do a protest song and be very explicit in the language, but there’s no nuance there.

I see it every now and then, but it would be nice if there was more widespread traction on like, well, what is music being made by Palestinians? And what is it saying about where they come from? What is music being made by people who are living and surviving in the south of America that are trying to exist in this space where they have found home, and what does it say about who they are and where they’re from and their community? Those ideas to me are more important than explicitly writing a song that is focused against whatever political party happens to be in power at the moment, because those things aren’t evergreen.

What’s next for you?

I have a book tour; I have a book launch event in Toronto and I have a few dates in America—it’s an interesting time to go to America to read about being trans, but here we are.

I write a newsletter called Anxiety Shark. And I’m working on a novel—it’s a queer love story that takes place at the Vans Warped Tour at the Calgary Speedway in 2002, which is the Vans Warped Tour that I went to in 2002.

I’m hoping that people like my book and ask me to write another one because I’ve got a lot of ideas and I really want to keep writing.

The Dad Rock That Made Me a Woman launches at Another Story Bookshop in Toronto on May 9 and is followed by U.S. tour dates through May and June.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra