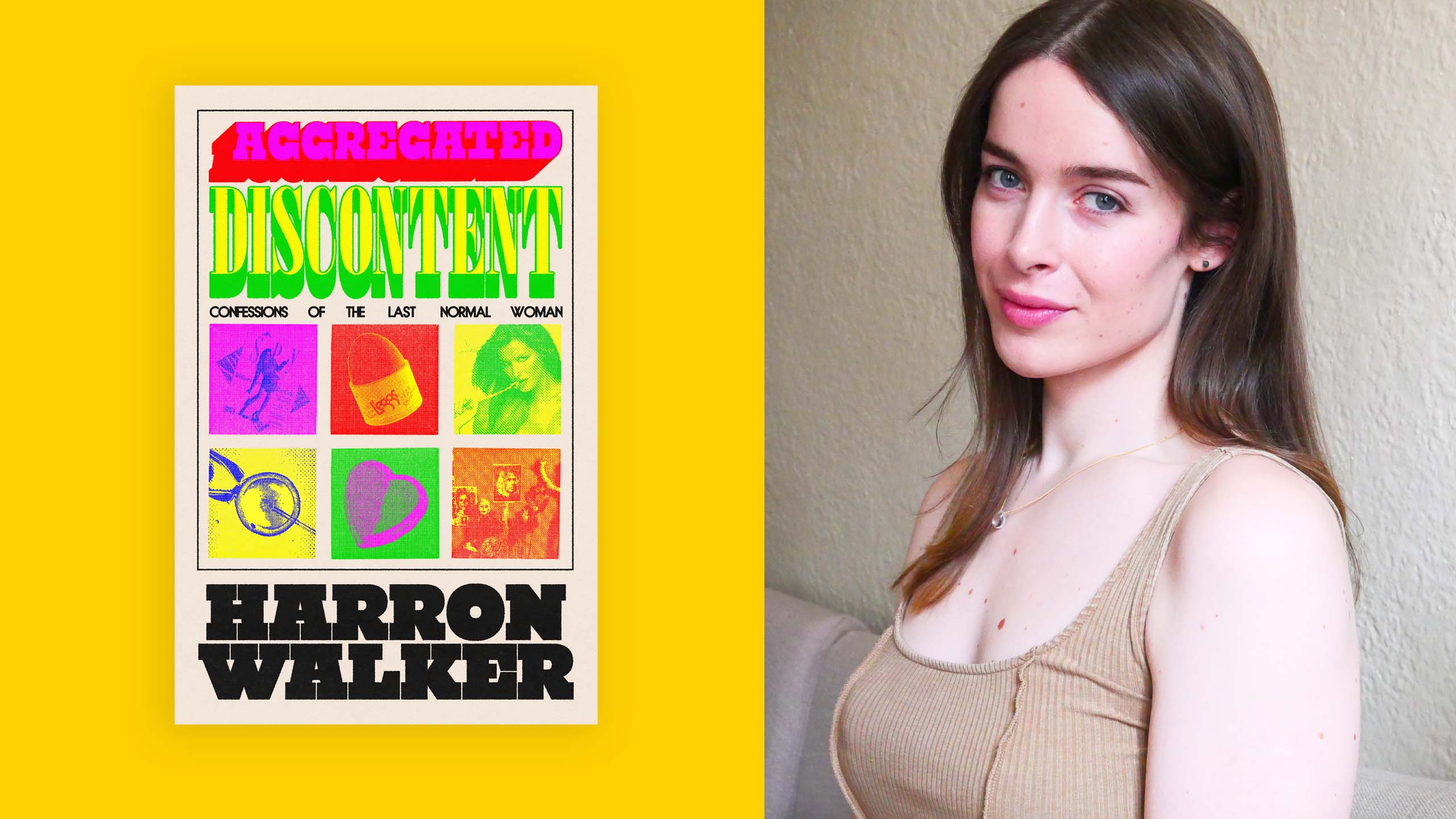

Harron Walker is not new to being dauntless. Be it her 2021 W Magazine column Burning Thoughts, on the highs and lows of a 30-something New York City resident, or her voicey pieces on Jezebel (all of which are only a teaser to her amusing and witty posts on X), the award-winning journalist continues to make her mark in her analysis of humans, the world and their relationship with it. Her new book of essays Aggregated Discontent: Confessions of the Last Normal Woman muses on criticism, play, humour and the faulty systems of American capitalism that it all always boils down to. Partly memoir, fanfiction and investigative, her debut is exactly as you’d expect: unexpected.

“At work I’ve been threatened, berated, belittled, propositioned, pelted with merchandise and worse,” Walker writes. “But those experiences with customers, readers and others are not what I worry about when I start a new job. Rather, it’s the memory of every old boss that haunts me to this day.”

Trans healthcare, one of Walker’s areas of expertise as a journalist, plays a significant role not only in Aggregated Discontent, but in her career at large; working in fleeting newsrooms, or under unfit management, insurance through work had been the key to her accessing of gender-affirming care. If anyone is to criticize the systems of power that require working-class people to struggle in accessing basic necessities, chances are Walker already has everyone beat.

“What could we accomplish—individually, and as a collective— if so many of our lives, trans or cis, didn’t revolve around trying to get healthcare?” she writes. “What would we be capable of if none of us had to worry about answering that perpetual question of access?”

There’s also a chapter on trans artist Greer Lankton, a sculptor of visceral dolls who died in 1996, wherein Walker finds pieces of herself reflected in Lankton’s past. She unearths the dollmaker’s tumultuous life story, digging through archives as far as photo-booth film strips Lankton took of herself throughout her life, every caption on the photographs opening new windows for Walker to see through and share with the world. In one of Lankton’s sketchbooks from 1977—a time she lost and found herself over and over—the artist wrote, “I swear to become my body.”

Be it Harron’s chronicles of working for an incompetent yet micromanaging boss, an invasive yet anti-climactic revelation during a TSA pat-down or her venture into several Lush stores in New York City claiming advocacy for trans people, the breadth of Walker’s words funnel into the same cup of all things bodily: pain, justice, autonomy and endurance.

Aggregated Discontent isn’t a book that bashfully catches the world up on how the decorated journalist got here; it is an amalgamation—an aggregation—of what she can sculpt and chisel with the flair she has garnered on her very way here.

Harron spoke with Xtra about being a Reference Girl™, wanting more out of hollow victories and the love she has for the trans women in her life.

Could you walk me through what made you decide to pursue this essay collection? In other words, why a book? And why now?

Back in early 2021, I was working on a column for W Magazine. I was getting some attention for the column installments that I was doing, sort of on the backs of other work I’d been doing over the years. And Ben Greenberg, an editor at Random House, reached out to me and said, “I really like this column. I like your writing. Have you ever thought about writing a book?” At the time, I was nine months out from a layoff from digital media where I’d been jumping from sinking ship to sinking ship, just trying to maintain access to healthcare until my surgery speed-run was concluded.

What I had written at the time, which is now in the final book, was the essay “What’s New and Different?” It originally began as a freelance piece in the summer of 2020 as a smaller-scale, very classic, 1,200 words, mid-length, personally inflected cultural, film and art criticism about the boss from the Lizzie Borden film, Working Girls. The more I worked on the edits with the brilliant Haley Mlotek, the more I was like, “I think this is actually a bigger piece,” and suddenly I was writing braided fanfiction—then it was 4,000 words, then 5,000, then 6,000—and I was just like, “I think I have to pull this essay.” I didn’t know exactly what the whole picture of this essay collection would be when I first began work on it, but I knew that this essay would be a great starting place because I was just very motivated and moved by it.

I thought, “What are pieces I have wanted to write for years, but haven’t?”

I imagine for those in the journalism world, “aggregate” might be a familiar term, but in this book title’s context, what does “aggregated” mean to you? And what is the significance of “discontent”?

I spent so many years in different writing jobs spewing aggregated content at a rapid clip, trying to help a website get BuzzFeed numbers by pumping out six blog posts a day about what Miley Cyrus or Selena Gomez posted about on Instagram. Looking at the different news sources on my feed, aggregating that information together and producing aggregated content. I twisted that into aggregated discontent.

A lot of what I’m writing is about smaller things that are manageable or tenable in individual instances, but in the aggregate become very untenable. For instance, the one phone call to your insurance company to appeal a decision that denies you healthcare is doable, but the 92nd time you have to make that phone call isn’t. Or the first time that some guy on a date is weird about your body—which he knew you had the whole time—you can let it roll off a duck’s back, but when it happens over and over, you can’t help but internalize a lot of it. So, thematically, I think it speaks to a lot of the subject matter of the pieces as well. I also just like wordplay!

There’s a heavy-handed cheekiness and humour that pairs really strikingly with the aggregated discontent. You are also a Reference Girl. Even the notes page in the end alone has 239 citations, which probably isn’t even all of it if you were to cite everything you referenced. Talk to me about how you’ve cultivated such a capacious wealth of things to piece together.

Similar to how ravens show affection by repeating phrases back to each other, I feel that way using references, intonations, phrasings, with my friends where it’s not even relevant to what we’re talking about. When I was younger, I would just spend a lot of time on the internet, in my bed, propped up with the laptop, just going down flights of fancy on Wikipedia or YouTube. I’m not a top, but if I saw a digital hole, I was down it. But at the same time, what’s weird is that a running joke with my best friends is that I also have the worst memory of all time. A friend will send a TikTok, I laugh at it in a group chat, and two days later I happen to see it on my feed and I’ll send the same one and they’re just like, “Oh my God, what the fuck?”

Some chapters read so cinematically. How big of a cinephile are you, and would you write for the screen?

I would love to. I used to have this pipe dream, looking at the careers of people like Cord Jefferson, who went from writing for Gawker and now has won an Oscar for screenwriting and worked on Succession, or someone like poet Tommy Pico, who wrote these four incredible books and then was working on Reservation Dogs. Just people who’ve transitioned into a Hollywood setting after working in either media, publishing or both. The WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes have fully destroyed that illusion that I had, that it’s somehow like an industry for writers that is not being devoured by corporate management up top. Unfortunately it seems to be a feature, not a bug, to all of our shared creative industries. But I would love to work on any kind of storytelling where there is physical media that I can hold in my hand.

You write in an instance of minor panic and sudden relief while passing through TSA unscathed. You write: “It just felt sad. Depressing, in fact. Even a little bit horrifying. The limits of validation, of simply having one’s gender affirmed, had never been so clear to me than in that moment, in that hollow little victory I’d worked so hard to win.” What is it that’s underwhelming about moments like these?

I had a weird experience with a rental car agent earlier on that trip to see my brother and his fiancé in another state. I was then stressed approaching the TSA and I got through it seemingly all fine. Something set off—sweat under one of my breasts may have been the culprit—and so they had a female agent come over and go to second base over my shirt. I was like, “Well, I didn’t like that!” I didn’t like an agent of the state going underneath my breasts with their hands. At the same time there was this bittersweet victory to it, where the state had deemed me a woman and they and I know that because they sent a female agent to go do that process. In a really sick way, that was a gender-affirming experience.

What feels hollow about that is it reveals the limits of what I had been purely focusing on. Is this all that I wanted? Is my one goal in life to pass enough that an agent of the state will be like, “You’re a woman, so a woman is going to feel you up.” That’s what the hollow victory is, but that can’t be the goal of my life because being an assimilable, perfect subject as deemed by the United States government is a really sad goal. It’s an understandable one because it also will mean safety and security to a certain degree, but that can’t be the end goal.

One of the things that struck me while reading this book was how much love you have for the fellow trans women in your life, various levels of proximity aside. You mention Río Sofia, Cecilia Gentili, even brief quotes or nods to Raquel Willis, Torrey Peters and Gretchen Felker-Martin.

I love that it shows through. That’s a really amazing thing to hear about your own work. Trans women artists and writers have informed my thinking, my frame of reference, my political analysis, all of which are ever evolving. So many trans women are those compasses for me. I don’t think we exist in, like, a silo, [because] there is a whole school of trans women’s thought and trans women’s art that inform my thinking and writing.

In the best possible way, nothing I do is new, nothing most of us do is new. We all have these precedents, because—to paraphrase something Morgan M Page said, there is an invented novelty to transness and a forced cultural and historical amnesia that allows us to think the new generation of people are suddenly trans. And it’s like, no, we have so much that we’re building off of, and that’s definitely a goal of my writing: to situate itself within existing legacy and canons because I love the other works in there, and it would just be an honour to be another link in that chain.

What do you make of the current time that we’ve been witnessing the past four months since Trump’s inauguration? Looking ahead, what do you have your eyes set on and who are you holding on to?

It’s both very clear and obvious, and at the same time very difficult to grasp. It’s as if the reactionary backlash that was mounting for years was like climbing up the roller coaster, and it is fully going downhill. The right-wing evangelical religious Christian fervour driving a lot of it is very classically American, but Brazil was talking about gender ideology almost 10 years ago. The Polish government has been talking about gender ideology. It also might surprise you to learn that the U.K. is a little bit transphobic on a governmental level! They keep it very tightly under wraps, but I think there is a global reactionary backlash to trans people among other marginalized groups. And unfortunately, it does fit into an ebb and flow kind of history—in the United States, at least. The last time we saw this was in the late ’70s/early ’80s. But I don’t know where it stops now.

Understanding privilege dynamics, interpersonal power dynamics has also served to make me think. I’m white, so I actually shouldn’t make this about me; this about other people and I need to be in solidarity with them. I’m doing a lot of thinking lately about what my actual risk is, how much I am standing in my own way of understanding that, understanding other people’s risks, like in related and also escalated ways in comparison to mine.

I’m trying to just hold people close and hang out with my friends, have fun, not tune out politically and at the same time not resign myself to the narrative that people who would like to see people like us eradicated want us to believe about ourselves.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra