In our nine-part series, Queering Family, we meet people across North America who are redefining what it means to build and sustain a family. Whether supporting a trans teen coming out, creating a drag family from scratch or caring for other people’s kids, these parents, children and caregivers illustrate the myriad ways that fostering loving networks might just be a queer superpower. Previously, families across Canada and the U.S. allowed us to glimpse into their home life via snapshots. Below, series editor Stéphanie Verge brings us inside the new “Rainbow Wing” in the long-term care facility where her stepdad lives.

When the pandemic hit, my father and his partner, Nevil, were renting a two-bedroom-plus-den in midtown Toronto. They’d been thinking about downsizing for a while, and a couple of months into COVID, they moved to a one-bedroom apartment one highrise over. After settling in, Dad sent the new address to their contacts, along with a note: “Nevil no longer deals with his emails. If you wish to share something with him, please use mine.” Another change.

I’d first met Nevil 12 years earlier, in 2008, not long after he and my father got together. He hosted an intimate dinner party at his condo, which he’d had catered, despite being a great cook, because he wanted to focus on his guests. That night, his seating arrangement had me directly to his right and my father at the other end of the table for six—much better for getting to know one another and dishing about my dad, I was told. I don’t remember much of what Nevil and I discussed—just that he loved to talk. A former ad man (he directed commercials for Air Canada, General Motors and Canada Post, among others), Nevil was gregarious and charming and stylish and, at 78, 17 years older than Dad. He was also the first man my father had dated following my parents’ separation a year earlier. Though entertaining, the evening was admittedly unusual.

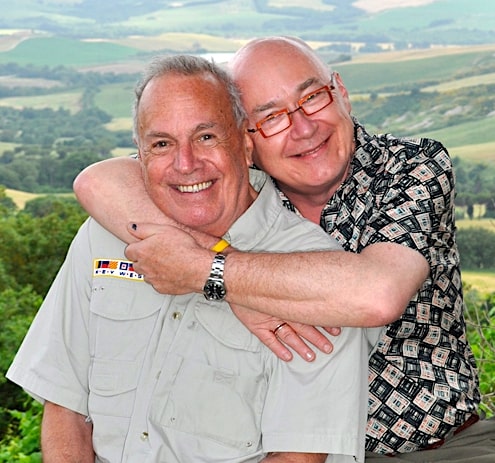

Nevil Pike and Charles Verge in 2011 during a tour of the Mediterranean. Credit: Courtesy of Charles Verge

In the ensuing decade, Nevil sold his condo and he and Dad rented a few different places around the city, including a Victorian pile in the Annex that had allegedly once been occupied by Queen Latifah. They eventually bought a condo in Etobicoke, only to sell it a few years later, anxious to return to the bustle of downtown. It seemed to me that they were more often on a cruise or travelling for one of my philatelist father’s stamp shows than they were at home. Dad had found someone as keen on a peripatetic existence filled with new people and places as he was. Every time I visited them, Nevil was on his laptop looking up flights or ships.

By 2019, they were travelling as much as always, but Nevil’s mind had begun to wander. If my father had to be away without him, he would arrange for someone to drop by the apartment every day or two, just in case. Nevil’s doctor suggested my father get Nevil on a waiting list for a long-term care home immediately, because a spot would likely only materialize in three to five years. Along with COVID, the following year brought an official diagnosis for Nevil: dementia and Alzheimer’s. Now, instead of planning trips, he was spending most of his days sleeping, watching TV or sitting on their 19th-floor balcony overlooking an enormous dog park. At night, he was often awake for hours, confused and agitated.

In late 2020, to alleviate some of his own stress and fatigue, Dad hired a personal support worker to come in once a week. My sisters and their partners, who live an hour away on a good day, helped when they could. My wife and I called from our home in Montreal and emailed photos of our infant daughter, a sure-fire hit. Still, my father was burned out from the isolation and constant caregiving. And even though he was terrified of moving Nevil to a long-term care home during a pandemic, he kept hoping for a call.

Founded by two Hungarian brothers who came to Canada in 1950 to escape Soviet rule, the Rekai Centres have a long history of inclusivity. After arriving in their new country, John (a surgeon) and Paul Rekai (a medical staffer) opened Central Hospital, a private facility on Sherbourne Street in downtown Toronto. They wanted to serve not just Hungarians like them, but all immigrants. So the siblings hired multicultural staff to care for the patients, believing that familiar food and customs would promote healing. By the late 1950s, the hospital staff spoke a combined 30 languages and could translate for patients when necessary. Over time, the hospital turned public and its foundation decided to expand into long-term care. The resulting Rekai Centres—non-profit, multilingual nursing homes—opened as Sherbourne Place in 1988 and Wellesley Central Place in 2005.

When my father was looking for the right residence for Nevil, he considered a number of factors, but easy access was key. He wanted to be able to visit frequently and a long-term care home on the subway line would allow for that. But most of all, Dad wanted Nevil to be comfortable. He knew the transition from familiar surroundings to foreign ones was going to be difficult, especially given Nevil’s memory loss. In March 2019, he applied to five residences and was ready to bide his time. But as luck would have it, Wellesley Central Place called in September 2021 with a spot for Nevil. A move-in date was set for later that month.

Credit: Lito Howse/Xtra

Wellesley Central Place also had one thing going for it that no other residence did: physical proximity to the queer village and a stated interest in welcoming LGBTQ2S+ residents. Nevil had been out his whole adult life, albeit often discreetly. The last thing I wanted for him, or my father, was for their final years together to be spent facing judgment. The Rekai Centres were tackling that issue head-on: they had a “Champions” program, a recurring module for self-selected staff on how to create safer and more inclusive spaces for queer residents and workers. The centres were also working on an all-staff LGBTQ2S+ training program, including overnight sessions for the late shift. Most remarkably, the Wellesley Central Place was slated to open a 25-bed space for queer and trans seniors, dubbed the Rainbow Wing, in June 2022—the first of its kind in North America, according to Barbara Michalik, the executive director of community and academic partnerships and programming at the Rekai Centres.

Older LGBTQ2S+ adults are at greater risk of social isolation—and with it, potential substance abuse, depression and increased stress, according to this research report. Published by the federal government in 2018, it points out that close to half of queer elders don’t have spouses. In addition, many of them don’t have kids and often feel unwelcome at non-queer events for older adults. The same report lists “being part of a community” and “having access to appropriate services, such as LGBT-friendly/non-heteronormative residences” as protective factors that can significantly improve the lives of queer seniors. While there are a number of LGBTQ2S+ residences and retirement communities across North America, a wing within a long-term care facility is a different beast. A guide released by senior-focused organizations AARP and SAGE in the U.S. stated that 78 percent of LGBTQ2S+ adults distrusted healthcare systems and if they enter a long-term care facility, they will return into the closet to avoid discrimination.

The idea for the Rainbow Wing in Nevil’s long-term care facility was born in 2008, namely out of an interaction Michalik had with Gordon, a favourite resident of hers at Sherbourne Place. Some staff and residents had been doing their solid best to matchmake Gordon with a female friend, much to his dismay. Finally, Gordon came to Michalik and asked her to put a discreet stop to it. “I really don’t want to get married,” he told her. Michalik reassured Gordon that she’d bring it up with the concerned parties, then joked that his reticence must have to do with the would-be couple’s significant height difference. “That’s when Gordon put his hand on my shoulder and said, ‘I’m gay. Please don’t tell anyone,’” says Michalik. “And that was the day I decided I would do everything in my power to make sure no one under my watch felt like they couldn’t be themselves, especially in the end stages of life.”

Michalik began by partnering with different local LGBTQ2S+ organizations, first the Senior Pride Network, then Casey House. The centres founded a GSA (gender-sexuality alliance) in 2015, followed by a Pride event called Bridging the Gap, to encourage LGBTQ2S+ communities to become involved in long-term care homes. In 2018, Rekai commissioned an Ipsos survey that found that 94 percent of LGBTQ2S+ respondents over the age of 50 were in favour of a dedicated wing, one that would be staffed by a culturally sensitive team committed to breaking down systemic barriers in healthcare.

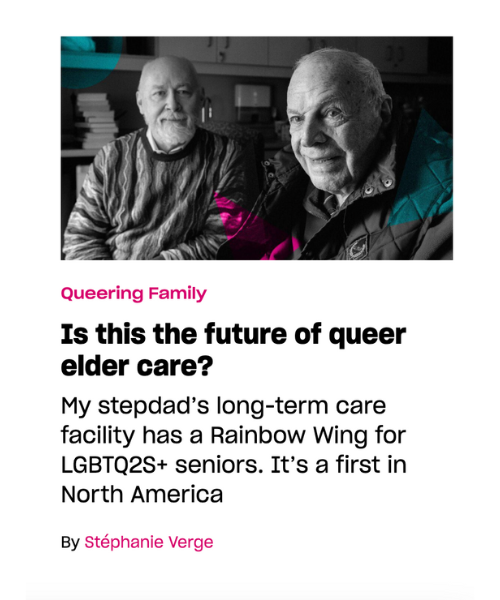

Charles visits with Nevil at the Rekai Centre. They have been together for 15 years. Credit: Lito Howse/Xtra

By the time the Rainbow Wing opened last June, Nevil had been at Wellesley Central Place for nine months. His dementia and Alzheimer’s had progressed to such a degree that my father, in consultation with the staff, decided against moving him to a different floor. Instead, Nevil would stay in his current room and participate in the wing’s activities when it suited him. It has been, given the circumstances, the best of both worlds.

The entrance to the Rekai Rainbow Wing. Credit: Lito Howse/Xtra

Danielle Herrington, manager of programs and volunteer services at Rekai. Credit: Lito Howse/Xtra

Walking through the Technicolor doors of the Rainbow Wing in late January, I happen upon what I later describe to a friend as “quite possibly the gayest thing ever”: a handful of seniors waving glow sticks to the familiar strains of “YMCA” by the Village People. “It’s exercise time,” explains Danielle Herrington, the manager of programs and volunteer services at Rekai. Clearly beloved around the wing, she’s been tasked with introducing me to a few residents. The first person we cross paths with is Sylvester, a lanky not-quite-50-year-old, the youngest resident at Wellesley Central Place. Flashing their red-and-green nails at Danielle, they’re focused on getting new batteries for the string of fairy lights around their walker.

Rekai resident David Karl Bernhardt. Credit: Lito Howse/Xtra

For now, the 25-bed wing houses just seven out queer residents; the other floormates don’t necessarily identify as part of LGBTQ2S+ communities. However, there are a handful of queer residents, like Nevil, who live in other wings. The Rekai team expects the number of queer and trans residents in the Rainbow Wing to rise, but imagines that there will always be a mix of LGBTQ2S+ folks and allies living side by side. The goal here isn’t segregation: it’s inclusion. For his part, octogenarian David Karl Bernhardt wouldn’t mind if the wing were a whole lot gayer. Current president of the GSA, Bernhardt is quite literally the flag-bearer for the initiative—he has a Pride flag hanging over the bathroom door in his room—and feels like the Rainbow Wing has yet to live up to its potential. “I was encouraged when it started up, but my expectations have not been met,” he says, laughing. Bernhardt, a former professor of psychology at Carleton University in Ottawa, is one of the few residents without dementia, making conversation and bonding with others difficult. “I would like to have some friends here,” he says simply.

Rekai resident James Coutoulakis. Credit: Lito Howse/Xtra

Until that happens, there are monthly Friday-night dance parties (complete with disco balls), a book club (selections are read aloud to members), TV nights (recent picks include Gentleman Jack, Drag Race and Grace and Frankie) and coffee time at The 519 community centre. Rainbow Wing resident and Gentleman Jack fan James Coutoulakis, 75, joins me and Danielle in the wing’s canary-yellow restorative therapy room. He’s sporting a black ball cap with “Boss” inscribed in gold letters. “I’m the boss man,” he explains, before settling into a chair across from me. Raised in Trenton, Ontario, he moved to Toronto when he was 18, and for many years worked at a Canada Post plant. As for his feelings about the Rainbow Wing, he confesses that at first he didn’t know why it was built, but its benefits have become clearer over time. “Even though I didn’t talk about being gay, most people just assumed I was. Now I do talk about it, sometimes. Because I feel like I’m at home here.”

Michalik would like more LGBTQ2S+ people to feel at home at Rekai, but for now she’s at the mercy of bureaucracy. The current waiting list for Wellesley Central Place has roughly 500 would-be residents on it. “When someone’s number comes up, I mention the Rainbow Wing to them and their families to see if it’s of interest. Once we cycle through this large group, applicants will be able to specifically state that they want to be on the wing,” says Michalik.

When asked why she believes initiatives like the Rainbow Wing are still necessary, Michalik shares two stories. The first is about a resident who, after coming out, became estranged from his adult daughters. When one of them had a baby during the COVID lockdown, she reached out to Michalik to ask for an in-person visit with her father; she didn’t want to leave things the way they were in case something happened to him. Michalik got permission from the centres’ CEO to set up a meeting in the backyard of Wellesley Central Place. “After so much tragedy, they got to have that moment of ‘Dad, look at my baby’ and she could see that he was safe,” says Michalik. “He moved into the Rainbow Wing soon after.”

The second story is about Gordon, the inspiration for the Rainbow Wing. Shortly before his death in 2017, he was in a great deal of pain and asked Michalik to hold him until he fell asleep. “I lay beside him for over an hour, holding his hand. After Gordon drifted off, a dietary aid came up to me and said that I shouldn’t have done that because Gordon was HIV-positive,” she says. “It was yet another moment when I realized that consistent, multidisciplinary education is so important—and that it takes time.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra