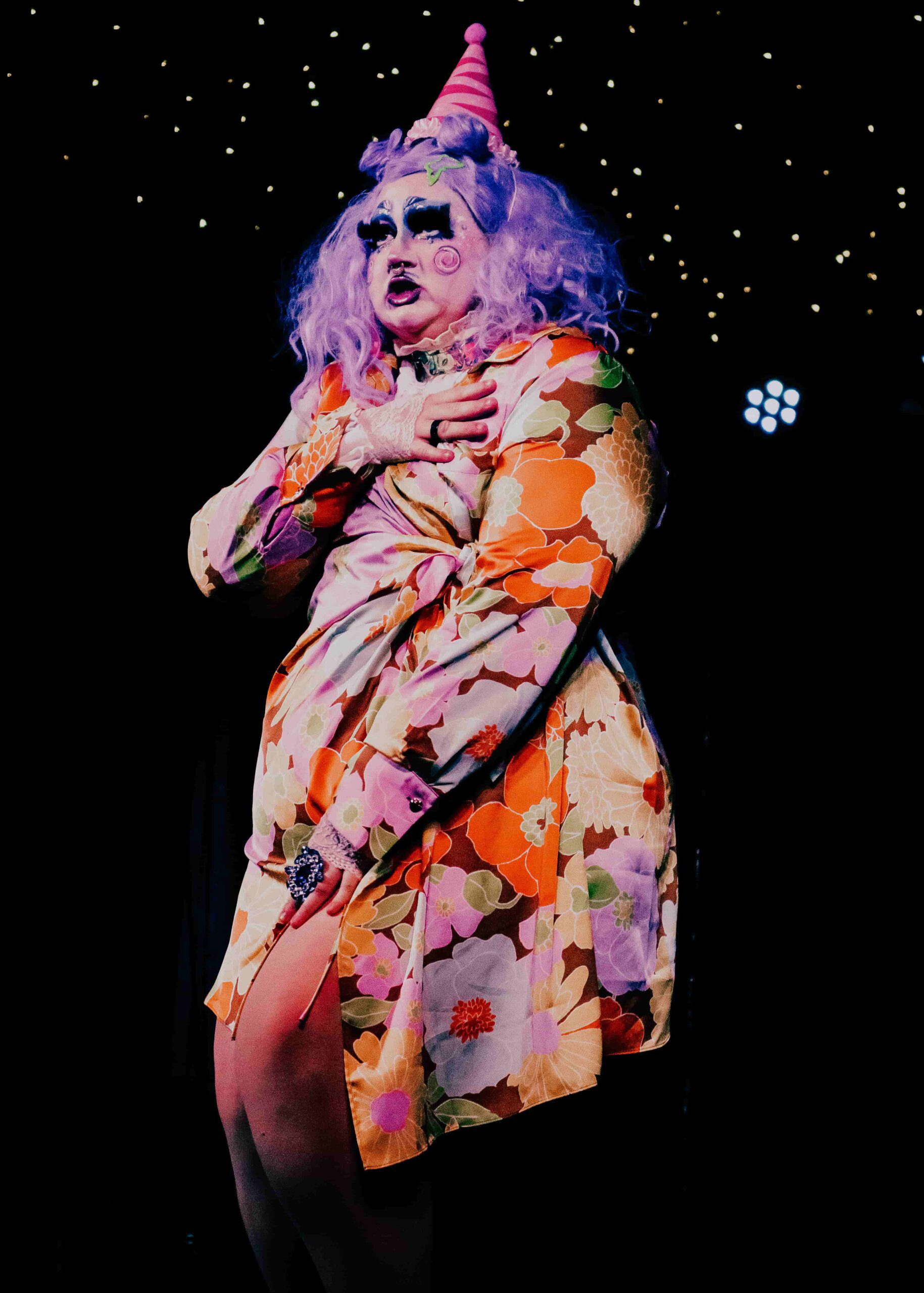

In our nine-part series, Queering Family, we meet people across North America who are redefining what it means to build and sustain a family. Whether supporting a trans teen in coming out, caring for queer seniors or helping to raise someone else’s kids, these parents, children and caregivers illustrate the myriad ways that fostering loving networks might just be a queer superpower. Previously, we spoke with a midwife and fertility expert who shared advice on how queer and trans people can create families. Below, Winnipeg drag performer Prairie Sky, aka Levi Foy, walks us through how she chose her drag family—called The Horrors of Lady Frances—and how they chose her back.

When I was in my late 20s, I went full-fledged into my gender journey. It was part of my healing from internalized misogyny and internalized homophobia—I was really trying to figure out who I was and who I wanted to become. I thought that I might be trans or that I wanted to be more femme-presenting, and drag was the place where I could come to terms with that. In 2011 and 2012, I was doing a master’s in Latin American Studies and returned to Mexico to conduct research. There, I became better acquainted with a trans woman named Beth Sua de Gyvez Gallegos, who is part of the muxe community, a recognized third gender among the Zapotec people. Even though I call her “Mom,” she wasn’t technically my drag mother—she never did my makeup or anything like that, but she imparted so much wisdom every time we met. She would always tell me that she didn’t do the same things I did, like drag. I would explain that she contributed to her community in a humble and meaningful way and that’s what I wanted to do, through drag and other avenues.

After Mexico, I moved to Fort Frances, in northwestern Ontario, and I was working for Family Services in my home community of Couchiching First Nation. There wasn’t much to do, so I had a lot of free time. I was living with my cousin and my grandpa, and in the evenings I would just play around with makeup. They were fine with it. Apparently, when I was learning to walk, my great-grandfather explained to the family who I was going to be. From that point on, everyone was always preparing for me to come out. When I finally did at 19, it was the biggest non-issue in the world—for everyone except me. I wish they’d said something!

I wasn’t a performance queen at that point, after Mexico. I would just do drag to go out and experience life through a different set of eyes. About once a month, I would travel to either Minneapolis or Winnipeg—both cities are equidistant from Fort Frances. At the end of 2013, I moved to Brandon, Manitoba, to be with my siblings. My grandfather had passed and I wanted to try something new. That’s when I started doing shows. It took me a while to figure out what kind of performer I was. For the first few years, there was a lot of gender-fuckery with some high glamour mixed in, and then there was a bit of camp. Eventually, I settled into my current iteration, which I describe as “classy trucker.” Somebody who outwardly looks like they have it all together, but is actually classy, trashy and sassy—kind of a mess. Really, I’m just a foul-mouthed person who likes to have fun.

Prairie Sky. Credit: Troy Watt

Eva Destruction (my niece)

By 2014, I was living in Winnipeg and had gotten a job at Sunshine House, a community drop-in and resource centre focused on harm reduction and social inclusion. I was doing drag most weekends, and that’s when Eva Destruction and I solidified our bond. We’d known one another since the early 2000s, when I was living in Couchiching. Eva, whose name was JP, was involved in the legal system as a minor. One of my cousins had asked if I wanted to watch over JP because he didn’t have any queer mentors. We had that mentor-mentee relationship right away, so when I started doing drag, she wanted to try it too. I didn’t really consider her my drag child, because we were learning together at the same time. I’d say I was more of an auntie, but she always called me her drag mom.

In December of that year, I became the program coordinator for Like That, which is a twice-weekly drop-in program at Sunshine House for 2SLGBTQ+ people who want to be in a space that isn’t a bar or a clinic. I’d set it up with another Winnipeg queen called Pharaoh Moans and it quickly became a meeting place for people who had been involved on and off with drag. We decided to hold a Drag Bingo fundraiser for Sunshine House, which became a semi-regular thing as it gained traction and more people became involved.

Purple Haze (my daughter)

Credit: Troy Watt

I met my first drag daughter, Purple Haze, at Sunshine House. She knew Eva and we hit it off. She was the first person who made me think, I’m going to mentor you and pass on my knowledge to you and I’m going to support you. Soon enough, out of Like That, we formed a collective of performers. We performed at the Good Will Social Club, we did drag queen storytime and we were invited to music festivals and different Pride events.

Things really took off in 2015 and 2016. People liked what we were presenting—it was a different type of drag than what was going on in Winnipeg at the time, which was part of the court system and involved a certain degree of pageantry. We were a diverse and eclectic crew, with a lot of Indigenous and racialized performers. We were a little more rough around the edges and unafraid to be “out there.” That resonated with a lot of folks.

Soleil Midowne (my daughter)

Credit: Deaghan McLeod

Not long after I adopted Purple Haze, Soleil Midowne joined us. I had met her socially and told her about Sunshine House. She said she might check it out. Then she said she might try a queer bingo, and things went from there. We put her in drag and she and Purple hit it off and they are now inseparable. They are the two elder statespeople of our family, our knowledge keepers. Their relationship is the glue of our family, not me.

Slaytana (my daughter)

Eva Destruction died in 2016, and when that happened, I didn’t want to take any more children. That same year, a kid I was mentoring outside of drag went missing and his body was never recovered. I couldn’t imagine taking on more loss, and I didn’t know if I could really be that kind of person—a true mentor—for other people. So I wasn’t actively looking for family when Slaytana and I started chatting on Grindr because she recognized me as a drag queen. She’d seen a couple of my shows and asked me to help her out. I loaned her wigs so she could go and play around. Then my friend Andrew Friesen, who is a producer at CBC, reached out about a story featuring people doing something they’ve always wanted to try for the first time. We agreed that Slaytana would be a great subject. When she got up on stage, she called me her drag mom and I thought, Well, I guess I’m her drag mom!

Olivia Limehart Sky (my daughter)

View this post on InstagramAdvertisement

In late 2017, when Olivia was about 10 years old, her bio parent Issa told me that Olivia really wanted to try drag. Issa is my age and we used to live together. My dad and Issa’s grandma were friends and their parents went to residential school together. All to say, Olivia and I have been from the same community for a really long time; we can draw a direct lineage between her bio family and mine going back six or seven generations. When I painted her for the first time, we bonded. We actually did a comedy routine together—I was the ventriloquist and Olivia was the puppet—and then I took her in as my child. Olivia doesn’t really need a lot of my help, though. She’s a spitfire and goes out there and does whatever she wants.

Buffy Lo (my daughter)

View this post on InstagramAdvertisement

Buffy is another Indigenous performer—we know a lot of the same people outside of drag and we were close friends before she started performing. In 2018, she reached out to me about joining our family, which I agreed to. But her case is a special one: Buffy has two moms, me and Cake, one of my best friends. Cake provides emotional support and I provide other types of support, like someone to get rowdy with. Buffy is very present on the drag scene and everyone knows who she is. She’s not leading shows, but she is always taking photos and posting things and engaging, which is just another way to be a leader.

Stara David (my daughter)

View this post on InstagramAdvertisement

Stara appeared on my radar in or around 2017. She was part of a group of folks who took part in a drag mentorship program at the Prairie Theatre Exchange, which was led by Vida Lamour and Pharaoh, and she was part of a group of gender nonconforming performers called Slunt Factory that was doing a form of camp and grotesque drag. I really took a liking to her, and one night I sat down with her at the bar at Club 200 and asked if she wanted to be a part of our family. I’d checked with Purple and Soleil beforehand to see if it was okay and they agreed that she would be a good fit. So that’s how we adopted Stara—it was a group decision.

By that time, Purple and Soleil had taken on leadership roles within the family, partly because of how busy I am with work. I’m honest when people come into the fold: I may not be able to do all the things they might expect. If you look at the old names in drag, those mothers would teach their children how to do everything, from wigs to covering brows to padding to makeup. Expectations aren’t the same anymore, because people usually come into drag with a solid idea of what kind of performer they want to be and what kind of performers they want to emulate. I think what people are really looking for when they join a drag family is connection.

Our family’s group chat is mainly for bouncing ideas off each other, talking shit and sending memes. My deal is I’ll paint your face once and I can give you some hand-me-downs and I’ll assist you if you’re going to run in a pageant. But you also need to learn stuff on your own and figure stuff out with your sisters. Each relationship is different, but with Stara and Miss Gender, for example, it’s more of an emotional connection and a performance mentor-mentee thing. They came in with an established aesthetic.

Miss Assuma Gender (my daughter)

Credit: Deaghan McLeod

In 2019, Miss Gender—who didn’t yet have a parent—ran against me in the Miss Club 200 pageant. Feather Talia, a peer of mine, and I had a secret bet going: if I won, I would adopt Miss Gender and if I lost, Feather would get to adopt her. When I won, I asked Miss Gender if she’d accept being my daughter as a consolation prize. She was really excited and happy to join us because she’d been putting out feelers for a family. Again, Purple and Soleil had to be in agreement, which they were. (That isn’t always the case—sometimes they say no.)

We pick family members based on a few things: chemistry, definitely, and whether or not we like the kind of drag that they do. But we also ask ourselves if they are actively contributing to the community. Are they just showing up to their own gigs and then leaving? Are they attempting to build relationships with folks? Are they mean, are they too dramatic? Do they seem like they’re going to take our knowledge and then throw us to the side? These are all things that we take into consideration. Another big one is inclusivity. Are they actively engaged in the type of work that we do? Are they using their platforms to combat misogyny, racism, fatphobia, ableism? Are they engaged in those conversations?

Eva and I chose our family name, The Horrors of Lady Frances, for a reason. It’s distinctly political. I didn’t want to pass on my last name—that’s patriarchal and it can limit people’s freedom. If my children want to take my name, they can, but they don’t have to. The Horrors of Lady Frances comes from when I was studying history. I was reading the 19th-century journals of Frances Simpson, a British woman who married George Simpson, of the Hudson’s Bay Company. When she travelled from Montreal to Winnipeg by canoe, she made the officers and guides portage her piano. She wrote horribly disparaging things about Indigenous people and anyone who had settled in this land, so I wanted my family to be made up of people who would have made Frances Simpson’s skin crawl. I wanted people who would go against that embodiment of colonialism and heterosexism. Eva and I came up with the name early on. Because she wasn’t exactly my daughter, I wanted a collective name that didn’t immediately imply there was a hierarchy.

Corvo Sky (my child)

Credit: Troy Watt

Many of my family members have worked, or currently work, at Sunshine House. Corvo started there in 2020 and again, Feather and I both wanted to adopt them. It wasn’t much of a quarrel because Corvo is more like me personality-wise, and my other kids really like Corvo. They’ve done three shows at this point and are still finding their footing, so the whole family is working with them. It’s kind of like a group project.

Feather Talia (my fellow auntie, cousin and best friend)

Credit: Deaghan McLeod

Feather and I have been friends for a long time—when she moved from Regina to Winnipeg in 2018, she moved in with me, and then I went on to hire her at Sunshine House. She’s a much better drag queen than I am in a lot of respects. We’re peers, so if there’s somebody up-and-coming who needs a family, we’ll figure out how we want to do it. We’re not the matriarchs of the Winnipeg drag community—that would be Anita Stallion, Vida Lamour and Breyanna Burlesque. Feather and I are more like the cool aunts. She’s the young, hip one and I’m the older one who’s still kind of funny. Once every couple of months, my family and Feather’s family all gather at my place for dinner.

Hellen Bedd D’Sloot (my granddaughter)

Credit: Troy Watt

In 2020, Slaytana said she was thinking of adopting a child and wanted to know if that would be okay with me. I asked Slaytana to consider the usual things: What can you offer them? What can you contribute to their legacy and what can they contribute to yours? It wasn’t surprising she might want a daughter—Purple Haze has one, too.

Even though Hellen was technically my granddaughter, I didn’t have much contact with her. I was Miss Club 200 from 2019 to 2021 and was highly visible, so some of the younger queens were intimidated by me and too afraid to approach me, according to Slaytana. (I think it’s because I’m a Scorpio—I call people out all the time.) Hellen did, however, have a close relationship with some of her aunties, especially Miss Gender. So after Slaytana passed away last December, we had a memorial at Club 200. I was in the kitchen with some of my daughters, discussing whether we should adopt Hellen. We brought it up with the rest of the kids and took a vote. The results were unanimous. It was very serious and very intentional.

The drag family of Prairie Sky (middle) is called The Horrors of Lady Frances and includes (clockwise from upper left) Corvo Sky, Buffy Lo, Slaytana, Soleil Midowne, Hellen Bed D’Sloot, Olivia Limehart, Purple Haze, Miss Assuma Gender and Stara David. Credit: Miss Gender

The best part about being a mother is the connections you create. It’s being able to offer familial support to folks who may not have had that before. I’m blessed because I have a biological family that always accepted me and every part of my gender journey and my queer journey. The biggest gift that I can give these younger people is to provide them with a space and an opportunity to go on their own journeys while maintaining a connection to a family. Everyone in The Horrors of Lady Frances is tremendously creative and tremendously honest. It’s amazing to have these types of relationships and this network of really smart people to bounce ideas around and engage with.

When both Eva and Slaytana passed away, I felt like their deaths had been preventable on some level. So I do have a lot of regret and I wish I’d been able to provide more. That’s always the hardest thing as a parent: Am I giving enough? Am I being supportive enough and loving people in ways that they’ll respond to? What if I’d reached out faster? The expectation when you create a family is that the relationships will be sacred. Even though our families are founded on something that might seem frivolous, there’s an obligation there that extends beyond the realm of the club or the realm of that drag space. You have to nurture your bonds.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra