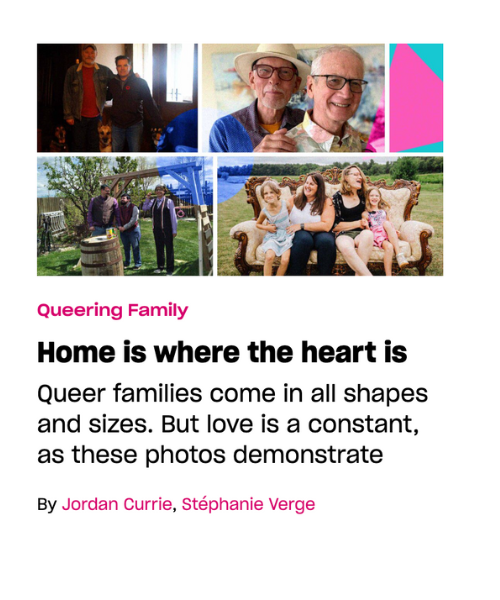

In our nine-part series, Queering Family, we meet people across North America who are redefining what it means to build and sustain a family. Whether supporting a trans teen in coming out, creating a drag family from scratch or helping to raise someone else’s kids, these parents, children and caregivers illustrate the myriad ways that fostering loving networks might just be a queer superpower. Previously, guest editor Stéphanie Verge outlined her changing notions of family after her father came out as gay later in life and as she contemplated having a child with her partner. Below, we meet parents who hope to liberate their children from binaristic gender assumptions, allowing their young kids to figure out how they identify on their own.

When Markus Harwood-Jones, Andrew McAllister and Hannah Dees began planning for a baby eight years ago, they knew their family would face scrutiny. A child raised in a queer, three-parent household (Harwood-Jones and McAllister are married, Dees is their co-parent) would most certainly face questions about their home life. But would using they/them pronouns for their baby bring an overwhelming amount of unwanted attention?

The parents had initially decided on he/they or she/they pronouns for their child—River—so that going stealth in certain situations would be an option. But even before River’s birth, Harwood-Jones noticed assumptions being made. “People at the hospital were pretty good about mostly using ‘they,’” he says. “But it did feel like the second we gave somebody the option of using ‘he’ or ‘she,’ they would.”

For River’s parents, gendered pronouns just didn’t sit well. “We’d reflected on our own relationships to gender,” says Harwood-Jones, who is trans. “We definitely didn’t want to enforce the expectation that our child would be cisgender.” After a heart-to-heart discussion, Harwood-Jones, McAllister and Dees decided to lean into their gut feeling. Raising their child in a gender-neutral environment would be difficult, but it felt fitting.

Not sure who will see this, but wanted to share the news anyway –

Hannah’s pregnant and I’m one of the (two) dads!

We’ve been planning this queer little three-parent-family for nearly 8 years and it’s finally coming to fruition 💚#babyannoucement #family #pregnancy #queer pic.twitter.com/fR68NF7qMG— Markus 🌟 Harwood-Jones (@markusbones) November 7, 2021

“As queer, non-binary and trans parents we were already going to be subjected to homophobia and transphobia,” says Harwood-Jones. “If, because of that, we shrank from making what felt like the right parenting choices, we wouldn’t be giving our child their own space to grow into whatever beautiful person they are meant to be.”

Building blocks: what is gender-open parenting?

Harwood-Jones’s family is part of an increasingly visible group of households practising gender-creative parenting. Also known as gender-open parenting, the approach presents kids with a range of gender identities and expressions—through diverse toys, clothes and media—and encourages exploration. The approach can include opting not to reveal a child’s assigned sex or using they/them pronouns until the child makes a choice themselves. In short, the goal of gender-open parenting isn’t to achieve androgyny, but rather to avoid gendered expectations so children can self-identify more freely when they’re ready.

Elizabeth Rahilly, a sociology professor at Georgia Southern University in Savannah, says the traditional consensus among cognitive psychologists is that children begin to understand the concept of gender around two or three years old. By the ages of four to seven, they start articulating their own identity.

However, more and more health practitioners believe this process may be longer and more fluid than previously thought, and that kids may identify in different ways over the course of childhood. “Our understandings of ‘normative gender identity development’ are continually getting eroded,” says Rahilly.

Meanwhile, gender-open parenting practices have evolved to challenge the notion of assigned sex. In the past, parents of trans kids often had to “catch up” when their kids came out as trans, says Rahilly, who wrote a book on trans-affirmative parenting. But with increasing trans and non-binary visibility, more parents are understanding how the categories of male and female are as arbitrary as gendered stereotypes and norms.

“I think we needed to have that moment as a scaffold to the current one,” says Rahilly. “Trans awareness and the trans rights movement really helped people become more aware of sex and the limits of sex for understanding gender.”

Still, while the mainstreaming of gender-neutral pronouns over the last decade has supported the growth of gender-open parenting, it remains a niche approach, says Rahilly. “I don’t think this is an exploding paradigm,” she says. “The backlash it’s getting in the media makes it look like it’s everywhere.”

Safe haven: revisiting the storm over Baby Storm

In North America, there’s no story more closely linked to gender-open parenting—and backlash—than that of Baby Storm. In 2011, the Toronto Star published a piece on Rogue Witterick and David Stocker’s decision to keep the assigned sex of their then-four-month-old private.

“We’ve decided not to share Storm’s sex for now—a tribute to freedom and choice in place of limitation, a stand up to what the world could become in Storm’s lifetime (a more progressive place? …),” wrote the couple in an email to friends and family after the baby was born, which was excerpted by the Star.

After the article was published, Witterick and Stocker faced waves of criticism from strangers and loved ones, much of which was rooted in transphobia. Today, the Toronto-based couple says the piece failed to situate their gender-open parenting practices within a broader framework. “We looked like a family trying something completely random that wasn’t embedded within a thoughtful, reasoned, principle-based approach to the world,” says Stocker.

Witterick and Stocker believe that respecting a young person’s right to self-determination is integral to their health and well-being. Deciding not to reveal Storm’s sex was part of a power-sharing approach to parenting—one that challenged the notion that children aren’t competent enough to find their place in the world.

According to Rahilly, parenting has become increasingly child-centred and child-driven over the past 40 years. “The gender-expansive parenting model is very much informed by the idea that young children deserve to be active agents in their development as much as the parents,” she says. “Just because they’re young, it doesn’t mean they don’t know how to speak about their gender and that we shouldn’t give them credence.” As for the notion that gender-open parenting confuses kids, she says that’s a misconception. “People picture 18 to 20 years of absolute mayhem,” she says. “It turns out a lot of kiddos will let you know who they are early on in childhood.”

As part of their parenting approach, Witterick and Stocker practised unschooling, a form of self-directed home-schooling. Their three children each chose when they wanted to engage with formal schooling, which made for smooth transitions, says Witterick. But entering public school also showed the kids how institutions and people outside of their family would attempt to impose different norms.

“I do remember Storm saying, around the age of 11, something like, ‘Growing up in this family then being in different environments kind of makes you feel a bit like a freak,’” says Witterick. “Everyone’s a freak, it’s just some people are pretending to function in institutions.” For Jazz, the couple’s eldest, the decision to attend a high school meant facing microaggressions and transphobia. Still, even though there were challenges, Witterick can’t imagine making a different choice than gender-open parenting. “Our daughter, Jazz, is now 17, and she says, ‘I know for sure you loved me up and down and sideways.’ That’s the most important thing to me.”

Click the images to read the full series

For Gavin Kade Somers, parent to 16-month-old Amé, the decision to practise gender-open parenting is rooted in their experiences as a non-binary person. “I’ve done so much work to deconstruct gendered stereotypes, and yet there are things I’ve internalized,” they say. “So I wanted to try and reduce the amount that the world would put on Amé.”

Somers says their use of they/them pronouns for Amé is no different than a cis parent’s use of pronouns that are typically associated with the child’s anatomy. Either way, a parent is acting on behalf of their kid. “I’m making a choice. It may or may not be the right choice but I’m making it with intention,” says Somers. “And it’s one that I can talk about with different levels of understanding as my kid grows up.”

Amé recently started daycare, a move that came after Somers chatted with several providers to find one that would respect their child’s pronouns. In the process, Somers found themselves coming out to childcare providers again and again, explaining everything from their experience as a queer and trans single parent to the fact that Amé calls them Roo (short for kangaroo, “the one who carried you,” says Somers).

“Whatever environment I will bring my child into, I’ll do the work to try and set things up for them so they don’t have to do that explaining,” they say. Where they live, in Vancouver, Somers says it feels as though there are big enough pockets of trans awareness, understanding and community that they can be intentional about the spaces they inhabit with Amé.

Finding family: community connections

These days, Harwood-Jones, McAllister and Dees are focused on building connections with the wider gender-creative parenting community—through TikTok. Harwood-Jones’s account features glimpses of the family’s life, and he regularly posts videos answering questions about gender-creative parenting.

Shortly after Harwood-Jones began posting about parenting, a follower commented on one of the videos, noting that their child’s nursery had the same theme as River’s. After chatting, Harwood-Jones discovered that they were part of another three-parent Toronto family practising gender-creative parenting, and that their child is just two days younger than River. “We found each other because we have the boldness to be honest about who we are and how we live,” says Harwood-Jones.

The families get together every few months for playdates, even though right now the kids are “both two potatoes kind of smacking each other,” says Harwood-Jones. “But as they grow, they will know another family that looks a little bit like their own, and I think that’s really special.”

River recently turned one, an occasion Harwood-Jones announced on TikTok with a short video montage. River is shown playing, crawling and napping in various clips, wearing dresses, flannel, dinosaur-themed clothes and a Pokémon onesie.

Harwood-Jones says the family has been trying to dress River in a range of outfits so they’ll always be able to find pictures that resonate, no matter how they identify later on. That’s something Harwood-Jones has sometimes found challenging, as a transmasculine person who was put in frilly dresses for childhood holiday photos.

He hopes that by presenting River with a multiplicity of gender expressions, identities and relationships, they’ll have a framework in place to support them when they’re ready to talk about their identities. “The dream would be that River never has to go through the terrible feeling of sharing with your family that you are not who they expected you to be,” says Harwood-Jones.

“Even if River grows up to be a super normie cishet, so what? They got to experience this beautiful variety,” he says. “And they’ll know they’re being exactly who they want to be, and need to be, in the world.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra