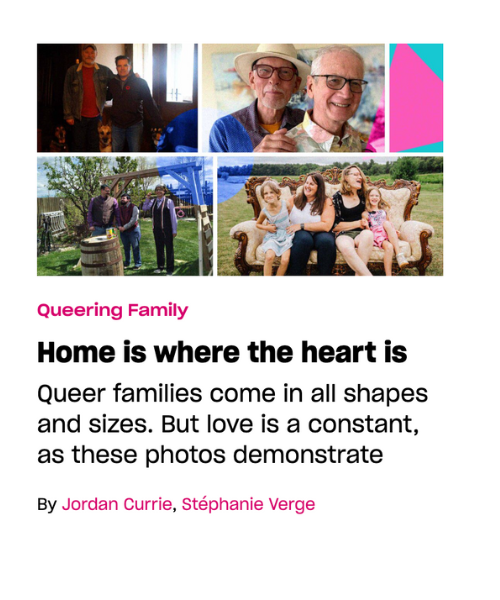

In our nine-part series, Queering Family, we meet people across North America who are redefining what it means to build and sustain a family. Whether supporting a trans teen coming out, offering advice to queer and trans people who want to have kids or caring for queer seniors, these parents, children and caregivers illustrate the myriad ways that fostering loving networks might just be a queer superpower. Previously, Indigenous drag performer Prairie Sky spoke about the bonds she’s forged with her many drag children. Below, Em Norton, a non-binary and transmasc nanny, shares how their work life and gender journey intersect and even enrich one another.

For the first 17 years of my life, my mom ran a home daycare in our small town just outside of Ottawa. I was forever surrounded by children, their sweet laughs and head-splitting tantrums a constant soundtrack. The house was littered with toys long after my siblings and I outgrew them, and our cupboards were packed with cookies shaped like woodland creatures, raisin boxes and applesauce.

The controlled chaos was at times uninviting (I was a shy child), but as I got older, I grew to love helping my mom. The kids who spent weekdays at our place were the first ones I babysat on weekends once I turned 13. On snow days, my mom would enlist my brother, sister and me as entertainment, and the kids were more than delighted to trot us down to the basement to play indoor hockey or to feast on pretend dishes. Some of my favourite moments as a teenager involved playing and chatting with the kids, and witnessing the profound love and trust they had for my mom. The way they leapt into her arms when they arrived in the morning, nestled into her when they were sick and developed inside jokes with her were things I hoped to inspire as a caregiver.

Since those early days of babysitting, I’ve had dozens of on-and-off childcare jobs and two nannying gigs. It’s a skill I’ve fallen back on when I’ve needed to earn money, whether after graduating university or in between writing jobs and apartment moves. But there’s a reason beyond convenience that I turn to nannying as opposed to food service, housekeeping or admin, which I’ve also done: it’s rewarding. Being able to witness a child discovering the world, learning new things and becoming proud of themselves fills me with gratitude.

In the summer of 2021, I took a position nannying for a Toronto couple with 18-month-old twins. On the surface, it was like many of my previous gigs—except it was the first job I’d had since coming to terms with my gender identity. The first year of the pandemic, during which I rarely saw anyone but my partner, had been a period of profound self-discovery. I had realized I was non-binary and transmasculine, and as relieved as I was to feel more solid in my identity, stepping out into the world was intimidating. I hadn’t begun to transition socially or medically and hadn’t told anyone except a few close friends. So, in many ways, the prospect of a nannying job was comforting—I knew I belonged in that role and that knowledge steadied me.

When the twins were around 20 months old, they started talking more and using my name. It felt like we were developing our own unique relationship. One evening after my shift, their mom texted me: I asked P if he had a good day and he said “Em!”

He called me Em—even though his parents call me Emily. It felt like he saw me clearly, without explanation.

The bond I’ve developed with the twins, and even their parents, is undoubtedly familial. Whether it’s taking part in family meals or hearing about their parents’ workdays, I feel like part of the household. And as I fall asleep in my apartment across town after an 11-hour shift, I still find myself thinking of them. I can hear the twins’ voices trying out new phrases and I wonder what crafts they might like to do the next day. They’ve become more than work—they’re now small people I love.

There are times when I’m nannying that I feel completely in tune with my nurturing side, the part of me modelled after the women in my life, the part that is keen to make things better when someone is hurting. I find myself in step with the rhythm of the kids’ routine, helping them when they need it and letting them handle things when they don’t.

But there are also times when I feel worn down and even stripped of my identity. Nannying is underpaid and the hours are long. What I can accomplish in a day depends on the whims of two tiny creatures. And the way in which many people view me can be reduced to a handful of words: “You’re a very lucky woman!” courtesy of an old lady watching me admiringly as I push a double stroller uphill through the rain. I know that many people have to censor parts of themselves at work, but working in this feminized job, it sometimes feels like the woman-perceived part of me is the only one that exists. It’s like the rest of me has to be set aside until the day is over and I can come home to myself again.

Other days, I notice how working with kids helps me worry less about my own issues with gender, including whether or not my transmasculine identity is tamping down my gentle side. Caring for the twins has forced me to acknowledge the ways in which I perpetuate negative stereotypes of masculinity. Being transmasculine doesn’t have to mean relinquishing my tenderness—it actually just gives it a new place to grow. My nurturing instinct and my gender nonconformity aren’t mutually exclusive—in fact, they are intertwined. Ultimately, nannying has made me more comfortable in my gender and allowed me to embrace masculinity and androgyny in my own way.

That comfort level isn’t necessarily shared, however. As a non-binary nanny who presents as less feminine than I once did—I keep my hair short, wear androgynous clothes and eschew makeup—I notice how differently some people treat me. Now, when I’m at the park with the kids, there are not-so-subtle questioning glances and more reticence to engage emanating from parents and other caregivers. Even though I’m confident in my abilities to care for the kids, the clear shift in attitude unnerves me.

Ultimately, nannying has made me more comfortable in my gender and allowed me to embrace masculinity and androgyny in my own way.

I don’t think my anxiety that perceived masculinity, androgyny or even queerness could be an issue in childcare work is totally unfounded. According to research released by Statistics Canada in 2021, more than 95 percent of childcare workers are women. When one group dominates a profession, anyone who looks different may be questioned. The more “not woman” you are in this work, the less you may be trusted. It can certainly feel that way to me.

As a result, I often find myself trying to negate my gender nonconformity while working. I overcompensate with self-edits when other people are around, whether by amplifying the high-pitched coo of my voice as I comfort the kids after a scraped knee or by adjusting my body language to replicate that of the mothers I’m in conversation with. I am not immune to the societal expectations of how a woman should behave, even though I am not one.

Despite how uncomfortable certain onlookers may make me, my relationship with the kids has the opposite effect. Nannying is gender-affirming—even life-affirming, I’d say. At three years old, the kids aren’t aware that I get paid to come over. They just know that I show up to take care of them and play all day. In warm weather, we bathe snail shells in the backyard under the hose and I blow bubbles for them to chase and pop. On winter days, they pile onto a sled and I pull them up and down the frosty slopes in their backyard. With them, I am uninhibited by societal constraints and gender expectations. With them, I have my guard down. With them, I am Em.

Caring for the twins has helped me connect more with myself and, in turn, being transmasc and non-binary has made me a better nanny. As I continue my journey toward self-acceptance, I am able to show up wholeheartedly for the children under my care.

I am most myself as a nanny, in many ways. I’m my inner child, a queer kid who just wants to imagine and play. I’m my mother, who taught me what it means to care and showed me I could be like her. And I’m my present and future selves: someone who is confident in their ability to care, and someone whose gender nonconformity is an asset, not a burden, to their life and work.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra