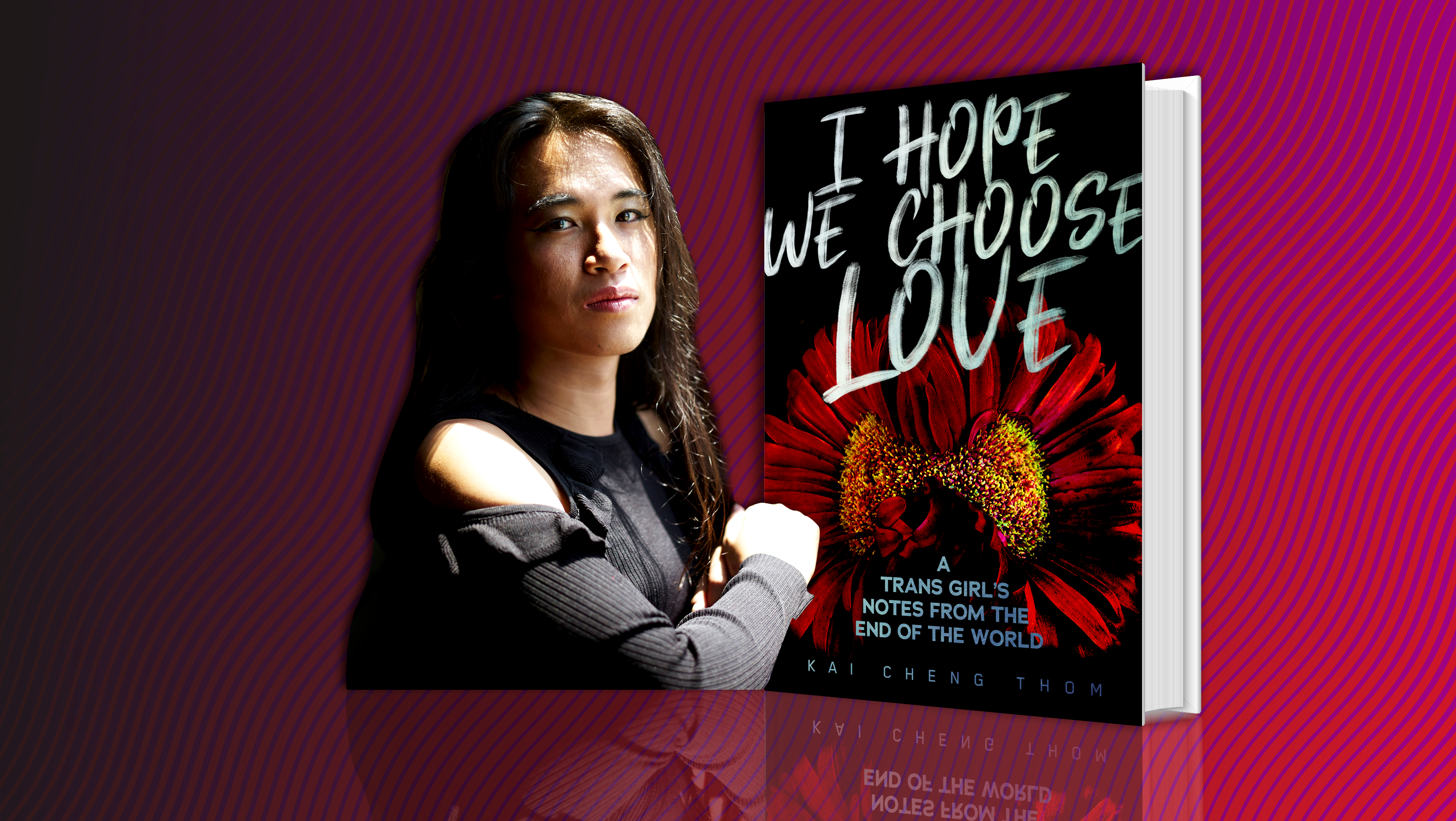

In her urgent and powerful new collection of essays and poems, I Hope We Choose Love: A Trans Girl’s Notes From the End of the World, author and Xtra columnist Kai Cheng Thom tackles the questions of community, love, justice and healing during in our current cultural, environmental and political climate. In this exclusive excerpt, Thom analyzes the problem with punishment and accountability processes, and offers a vision of what love-based justice could look like.

You have the right to tell your story … You do not have the right to traumatize abusive people, to attack them publicly, or to sabotage anyone else’s health. The behaviors of abuse are also survival based, learned behaviors rooted in some pain. If you can look through the lens of compassion, you will find hurt and trauma there. If you are the abused party, healing that hurt is not your responsibility, and exacerbating that pain is not your justified right.

—Emergent Strategy, adrienne maree brown

I’m not a big believer in justice. That skepticism extends to the notions of accountability, restorative justice, transformative justice, and most of the related terms that have taken hold in social justice culture—though I do very strongly believe in integrity, honesty and personal honour. “Integrity” is a word you hear used fairly frequently in social justice circles, but honesty and honour, as I know them, are values that come to me through my Chinese family and upbringing. Honesty, in my family, means saying what you mean, even if it is unpopular. Honour means acting in a way that your ancestors would be proud of, even if it requires personal sacrifices to do so. However, “honour” is not a word you hear very much in social justice community, and I feel its distinct lack as an influence on activist conduct.

I used to be much more of a believer in justice. I had drunk the Kool-Aid, though I wasn’t ever really clear on exactly what justice meant. Rather ironically, I think a lot of people who are involved in social justice “activism”—scare quotes used because activism means a lot of different things to different people—aren’t too clear on a working definition of justice. There is a subset of folks, of course, who have thought about the definition of justice a lot, but my sense is there is great disagreement and confusion among them. And why not? Justice is a pretty highfalutin philosophical concept.

Over the years of my adolescence and early adulthood, I gave a great deal of myself to the idea of justice: Time, energy, dignity, health. I made huge personal sacrifices to try to live up to the leftist ideals of justice, particularly accountability—which in the circles I ran in had a lot to do with using the right political language (which always changes) and doing all the right political things all the time, and then admitting in no uncertain terms that you were guilty and “problematic” when you were inevitably called out for infractions. There’s actually a fair amount of good learning in that ideology—it teaches humility and listening to the voices of people in pain, which is pretty much always good in my book.

Unfortunately, the enactment of “justice” in radical leftism also played out in my life as a total invalidation of my boundaries (and I am not great at boundaries in the first place). For a time, I became quite valorized in my local community as a “good” upholder of social justice because I was very skilled at using the right language and doing the right things, and I tended to apologize unreservedly and perfectly when I “fucked up.” I now recognize this as a skill born of trauma: The ability to ceaselessly and accurately scan the people in one’s environment for a sense of what will please them, and then to enact it, no matter the cost to one’s long-term health. This skill is a brilliant short-term survival strategy, as most trauma coping strategies are, designed to negotiate the unpredictability and cruelty of punishment—and unfortunately, a punishment narrative is deeply embedded in much of social justice.

Punishment is not something that happens to bad people. It happens to those who cannot stop it from happening. It is laundered pain, not a balancing of scales.

—Porpentine Charity Heartscape, “Hot Allostatic Load”

I’m not a believer in justice because I have never gotten it from or against those who have harmed me. I really am not certain that it would be good for me if I did. I gave so much of myself trying to obtain justice for others, and it eventually rendered me traumatized and deeply disabled. I’m saying that as a literal statement of fact, not as a metaphor or to be melodramatic: I am now sick. I can’t do things I used to be able to do without severe physical or psychological pain.

Many times in Social Justice Land, I was quite seriously taken advantage of and badly treated by white women in positions of power over me. This was done in public, when we were surrounded by so-called activists. Sometimes bystanders expressed sympathy to me in private afterward, but they never protected me or pushed back. I am, of course, angry about this, but I don’t judge these vulnerable bystanders. I have done this exact same thing myself, many times: Witnessed exploitation or violence, and then tried to be supportive without actually taking a stand. It has to do with fear—of punishment, of losing relationships and social status.

I have seen many white women call for justice in situations of personal conflict, violence, and abuse. I have seen others do it as well, but it tends to be white women who get the most attention, because white women are assumed to be inherently innocent. The ideological “innocence” I speak of here not only refers to the literal “not guilty of wrongdoing” but also encompasses a sense of “purity” or “virtue” that makes it blasphemous or deeply evil to be accused of harming a white woman. This, of course, is part of a historical legacy of the use of white womanhood as a justification for violence against people of colour—not too long ago, it was common for men of colour, especially Black men, to be lynched or imprisoned for supposedly endangering the virtue of white women, a practice that continues in more covert forms to this day.

“Punishment does not end violence; on the contrary, it breeds it.”

Interestingly, I have also seen many people who are not white women attempt to claim the same kind of “innocence” in their own calls for justice—which entails, first, that the “innocent” person is seen as free of all and any responsibility for the situation and, second, that the “guilty” party is then rendered available for punishment. The logic then follows: If someone has done something bad, it is okay to be aggressive or even violent toward them.

We like punishment in Social Justice Land (lots of people, in many societies and subcultures, like punishment). Of course we do. It feels good to see someone who has hurt you receive a painful consequence for their actions, and we get that feeling by proxy when we see someone who has hurt someone else get punished. I don’t think that’s wrong in and of itself. I have lots of revenge fantasies, and they are very, very comforting to me at certain times. The problem is the enactment of punishment and revenge (and, no, I don’t really see a meaningful distinction between punishment and revenge, though that is up for debate): pain and violence tend to replicate themselves, like a virus. Punishment does not end violence; on the contrary, it breeds it.

We like to think of our punishments as humane; that is, we like to think of them as not-punishment. We prefer to tell ourselves that our punishments are natural, justified consequences. Because punishment feels good in the moment, but it also makes us feel guilty. Leftists, in particular, do not like to see ourselves as perpetrators of cycles of violence because we claim to abhor violence. One notices, though, that the prison-industrial complex and legal criminal justice system also make claims to the moral sanctity of their use of punishments.

On the left, there is a nominal preference for “self-crit” and “accountability,” rather than outright punishment, which usually means that the person who is understood to be guilty of an offence must immediately (immediately!) denounce themselves, often publicly, and then perhaps engage in some sort of reparative labour. This has the potential to be positively transformative but requires great skill to do successfully. We cannot be forced into immediate personal and spiritual growth—we must come to it willingly, or else we only end up disappointed at best and retraumatized at worst. This takes time, resources, and compassion on all sides. It takes compromise and is not immediately gratifying (or even gratifying in the medium term, frankly).

In social justice culture, accountability is enforced by public shaming and shunning, which often continues to affect the person’s social standing long after the act of accountability/reparation is done. Collective measures for assessing the effectiveness of accountability processes and the degree of enforcement necessary are not in common usage; indeed, some people in social justice communities seem to prefer an endless bombardment of online call-outs to the resolution of conflict. The human dignity of someone who has done something “problematic” becomes deprioritized at best and outright trampled at worst.

We have all seen the dogpile of social media—people being relentlessly verbally attacked for making problematic statements despite their good intentions, or even for expressing legitimate differences of opinion. The movement seeks uniformity because uniformity and purity feel safe. This, too, is the language of trauma. I have also seen people doxed and stalked both online and in person. I have been stalked, by someone I had never met or spoken to, because they perceived me to be “abusing” them by not responding to a Facebook friend request. I have seen my friends spread rumours about others in community, advocating for shunning and ostracization over allowing ideological disagreements. On rare occasions, I have seen activists encourage the physical beating of abusive people in community.

“We prefer to tell ourselves that our punishments are natural, justified consequences. Because punishment feels good in the moment, but it also makes us feel guilty.”

As a whole, we have a tendency to escalate rather than de-escalate conflict. In our (rightful) desire to ensure that harm is not minimized or ignored, we use inflammatory language, binary concepts of right and wrong, and oversimplified narratives that more often than not increase tension and heighten rage and shame. We do not ask the questions that are central to transformative justice: Why has harm occurred? Who is responsible (beyond the individual perpetrator—as in, how is community implicated)? How can this harm be prevented in the future?

There are distinctions to made between punishment, justice, and healing. Punishment is a gratifying process of enacting revenge that also perpetuates cycles of violence. Justice is a slow process of naming and transforming violence into growth and repair; it is also frustrating and elusive—and rarely ends in good feelings. Healing is the process of restoration for those who have been hurt, and although justice can aid this process, my own experience is that healing is an individual journey that is almost entirely separate from those who have caused me harm. No apology, or amount of money or punishment, can give me back the person I was, the body and spirit I possessed, before I was violated. Only I can do that.

People who perpetrate violence are not the authors of it; they are the instruments of it. They are solely responsible for the violence they inflict on others. We are all responsible for the violence in our culture.

—Michael White, narrative therapist

I do not have much faith in justice, but I have no choice but to believe in it. The other option is nihilism—total lack of faith in humanity—which I reject. We must reject nihilism because that way lies fascism. We must reject despair and embrace healing, slow and imperfect though it may be, and turn instead to love—love strong enough to live without faith. I am trying to embrace my own healing. I am trying to love my own painful, wounded life. As adrienne maree brown suggests, I am trying to embrace growth and constant transformation, like a flower growing in poisonous radiation.

I am trying to let love emerge from my traumatized body.

“I am trying to let love emerge from my traumatized body.”

So if we must do the work of justice, I suggest that we begin by redefining justice. Rather than a lens of punishment, consequence, or even accountability, we might try understanding justice through an ethic of love. Concrete steps toward building this love-based justice might look like the following:

- We must create flexible, working, practical definitions of justice so that we understand what we are doing and what values we share. There might need to be different definitions of justice for different contexts, but I believe that justice is the naming of harm and the transformation of the people as well as the conditions that perpetuated the harm.

- We must be open to the notion that survivors of harm can also be perpetrators of harm. Survival is not a badge of purity, nor a shield from accountability.

- We must invest deeply and fervently in the dignity of human life. We must not give in to the urge to do harm, even in justice’s name. We must recognize, name, and transform the instinct to humiliate, harm, and coerce those we see as bad or as wrongdoers. No one is disposable.

- We must accept that we cannot force others to change their thinking or their beliefs. We can, however, set boundaries on violent behaviour, and we can enforce those boundaries.

- The practice of facilitating justice work demands complex skills and experience, and it requires great integrity. The facilitator of a justice process must operate honestly, transparently, and with an awareness of their own capacity for abusing the power of their role. As with any position of power, the facilitation of social justice may attract those more interested in that power than in the work itself, or it may present facilitators with the temptation to use that power unwisely. There must be guidelines and strategies to moderate the power of facilitators, and to prevent its misuse.

- Justice may not always be successful at making everyone, or anyone, feel good. We do not all have to like each other or be friends or share personal space. Justice should work toward reducing future harm through de-escalation, as well as ensuring that everyone has the basic resources they need to live, heal, and enjoy life—Yes! We have the right to enjoy our lives.

- Everyone has the right to access support while the work of justice is happening. Many seasoned practitioners of transformative justice suggest the use of “pods,” or small groups of community to create agile networks of support.

- The community must accept its own responsibility for producing, condoning, and reproducing violence. We cannot spend years—decades—in community spaces watching people act badly and hurt each other, and making excuses for them, and then suddenly turn around and act shocked when an individual names that violence. We cannot pretend that we had no hand in covering up, minimizing, and even encouraging violence. We cannot have parties where everyone is deeply intoxicated, and physical, sexual, and verbal boundary-pushing is encouraged, and then act as though “abusers” are all sociopathic monsters who have infiltrated our otherwise perfect communities.

- We must love ourselves. We must encourage love—love that is radical, love that digs deep. Love that asks the hard questions, that is ready to listen to the whole story and keep loving anyway. Love for the survivors, love for the perpetrators, love for the survivors who have perpetrated and the perpetrators who have survived. Love for the community that has failed us all. We live in poison. The planet is dying. We can choose to consume each other, or we can choose love. Even in the midst of despair, there is always a choice. I hope we choose love.

I Hope We Choose Love: A Trans Girl’s Notes from the End of the World is available now from Arsenal Pulp Press.

“I Hope We Choose Love: Notes on the Application of Justice” from the book I Hope We Choose Love: A Trans Girl’s Notes from the End of the World by Kai Cheng Thom (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2019). Reprinted with permission from the publisher.

Line break by BoxerX/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra