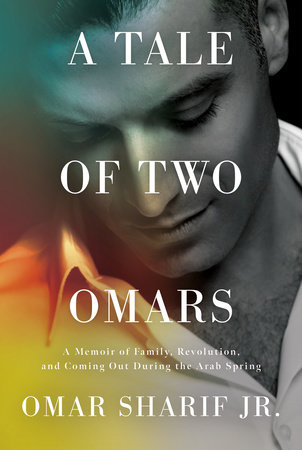

A public coming-out letter originally written for The Advocate magazine during the Arab Spring in 2011 forms the basis of actor and activist Omar Sharif Jr.’s new memoir, A Tale of Two Omars. Out Oct. 5, the book explores the many facets of Omar Jr.’s life as the grandson of one of the most famous people to ever come out of Egypt.

As a queer Arab who has lived in both the Arab world and North America, I was excited to read a story of someone also living between both worlds. The difference between the two of us, I learned, is that I didn’t grow up famous or wealthy.

Omar Sharif Jr. gets his name from his grandfather, the famous Egyptian actor Omar Sharif, who successfully straddled the worlds of Egyptian cinema and Hollywood, while also starring in British, French and Italian productions. The famous polyglot started acting in the 1950s—over 30 years before the birth of his grandson in Montreal, in 1983.

In A Tale of Two Omars, his first book, Omar Jr. writes about the many lives he’s lived trying to establish himself as his own person, separate from his grandfather. They include: Junior, the popular student at Queen’s University in Kingston; the mama’s boy in suburban Montreal; the go-go dancer in the city’s gay village; the half-Jewish, half-Muslim man in Canada and in the Arab world; the party gay in Mykonos; the assistant to a closeted sheikh in the Gulf; the actor in L.A. and the accidental activist. While a dozen pages are devoted to his childhood, in which he describes being bullied at school in Montreal and the luxurious summer vacations he spent in Egypt being passed between his grandparents (his grandmother was famous Egyptian actress Faten Hamama), the bulk of the book takes place during Omar Jr.’s adulthood.

“‘Not only was I gay—I was a hot mess,’ Omar Jr. writes.”

While at university, Omar Jr. takes on a new persona, asking people to call him, simply, “Junior.” He accidentally comes out publicly while on a date with Chris, a football player he meets on Gay.com who lives off campus with some of his teammates. When Chris’ roommates unexpectedly come home and try to walk into the locked basement where Junior and Chris are hanging out, Junior gets stuck halfway through the window while trying to discreetly flee. Chris ends up having to call emergency services. When Junior is rescued by firefighters, the event is witnessed by all of Chris’ roommates and several other university students. “Not only was I gay—I was a hot mess,” Omar Jr. writes about the scene.

Despite the humorous tone at the onset of the memoir, we soon find out that the young actor/activist’s life takes some dark turns. There’s a strong contrast between his experiences of immense privilege and the more difficult parts of his life, including his experiences of sexual assault by powerful men. As the book ping pongs back and forth between his struggles and the glamorous world he inhabits, my emotional response to it ping pongs between empathy and disappointment.

The most devastating part of the memoir is when Omar Jr. reveals that he was raped, abused and belittled by a sheikh he worked for in the GCC (Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf). Here is an honest portrayal of what rape and sexual assault can look like when it is perpetrated against men—particularly gay men—and the taboo of talking about it. He recounts several other occasions where men have sexually assaulted him; one man rubbed against his genitals at the Oscars, another grabbed him in public. With these revelations, Omar Jr. reminds us that this type of violence is everywhere—whether it’s in the Gulf or in Hollywood. In the book, he writes that he hopes that sharing his sexual assaults can help others come to terms with their own experiences of violence.

“Here I was at a conference to talk about human rights abuses, and a closeted politician had the audacity to grope me.”

Towards the end of the book, Omar Jr. recalls the moment he gave an address to the Freedom Forum, a non-profit organization that encourages support of the First Amendment to the United States’ Constitution, which guarantees freedom of speech. After the address, he writes that he and two other activists were invited to a meeting with a high-ranking parliamentarian. When taking an official photo, the politician guided Omar Jr. into place and grabbed his ass while the others weren’t looking. “After everything I had been through,” Omar Jr. writes, “I was still shocked; here I was at a conference to talk about human rights abuses, and a closeted politician had the audacity to grope me.” Despite the shock, he goes on to imply that a positive attitude can help him get over such experiences. “The bullies never went away, but what changed was my response to bullying. I was bullied in elementary and high school, in Beirut, and by the media, Egyptians, and political and religious authorities—and it hasn’t stopped. But once I learned to have self-acceptance and self-love—the bullying no longer hurt. […] People who bully others and spread hate are the weak ones.” His response makes sense, but lacks nuance when it comes to addressing abuse more broadly. Omar Jr. seems unable to tie his own experiences to larger conversations about sexual assault, victim blaming and shame.

Ultimately, the less relatable moments in the memoir appear in his sharing of his wealth and privilege. While Omar Jr. occasionally acknowledges his privilege in the book, his good fortune still influences the way he acts, speaks and lives, inevitably keeping him from deeper self-awareness. Writing about driving without a licence in Egypt, he reveals: “I somehow always felt above the law in Egypt; until I came out, just using my grandparents’ names was a get-out-of-jail-free card.” About doing his master’s degree in London, England: “To better adapt and meet people in London, I made a standing reservation for myself at Nobu, a Japanese restaurant in Berkeley Square, every Friday night.” The average person could not afford to eat at this high-end restaurant once, let alone every Friday night. These instances are mentioned casually, like when he describes his summers in Egypt with his grandmother. “Sometimes,” he writes, “we’d travel on her yacht in the Red Sea or to one of her homes in Agami along the Mediterranean shore.”

“Omar Jr. implies that he made this new contact on his own, a claim that feels out of touch.”

In late July, Franklin Leonard, founder of the Black List, an annual list that highlights unproduced and overlooked screenplays from the previous year, started a Twitter debate about nepotism in Hollywood. In the online discussions, Ben Stiller chafed at the implications that many Hollywood actors benefit from nepotism (his parents are the late Jerry Stiller and Anne Meara, both of whom were famous actors). Stiller tweeted that show business “is a meritocracy.” In his own account of his life, Omar Jr. implies the same when he talks about moving to L.A. to become an actor. He writes that he wants to succeed without getting in touch with his grandfather’s contacts, but does not acknowledge that being named Omar Sharif automatically opens doors for him whether he mentions his grandfather or not. Within the first couple of months of being in L.A., he meets openly gay six-time Emmy award-winner, actor and comedy writer Bruce Vilanch, who tells him that he has the same agent as Omar Jr.’s grandfather. Omar Jr. implies that he made this new contact on his own, a claim that feels out of touch. The weight of his grandfather’s name—and therefore his own—is undeniable. Even the title of the book references his grandfather, after all. By all accounts, Omar Jr.’s memoir is an example of the obliviousness of actors who come from fame and wealth.

Omar Jr. is also often politically oblivious. As a half-Jewish (his maternal grandparents were Holocaust survivors), half-Muslim person, it isn’t surprising that he contends with the State of Israel in his memoir. As an adult, he takes a trip to Israel with some friends—his first trip back since being there as a teen. Despite being followed through the Israeli airport because of his Arab name and his fluency in Hebrew, being strip-searched—a “hand-held metal detector” swiped “between my butt cheeks”—and being made to wait below the tarmac underground, away from his friends, Omar Jr. maintains, “I still had the most amazing time.” He writes that he didn’t want to engage “in the toxic and negative BDS [Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions against Israel] debates that others were having around” him at university. “I believe in engagement and dialogue above all—in finding common ground.” Often, Omar Jr. makes vague statements about the situation in Israel, exclaiming how enlightening and hopeful the experience of visiting the contested area was for him. That first adult trip to Israel, he proclaims, “left me hopeful that I would see a rebirth after devastation. Despite challenges and political upheaval, spring always follows winter, the light comes after the darkness, and hate can turn to hope. It was clear to me that people can overcome anything.” That sentiment is vexing in light of the recent illegal evictions of Palestinians from their homes in Sheikh Jarrah and Gaza.

The most eye-rolling evidence of Omar Jr.’s entitlement appears when he discusses the advocacy he did on behalf of Syrians during the 2016 refugee crisis in Europe. During his speech as grand marshal of the 2016 Prague Pride parade, he declared, “‘Refugee’ is a blanket term that lumps together so many—I suppose that I, too, am a refugee of sorts, even with my means and my family name.” The insensitivity of this statement, by someone able to easily move between many countries and continents, is shocking.

Readers coming to the memoir hoping for gossip about Omar Sharif Sr. will be disappointed. The only new stories about the late actor are sad anecdotes about his dementia and gradual loss of self. But it’s worth getting through the sometimes clunky memoir to enjoy the more tender moments of family connection and clumsy coming outs, and to get a look into the lifestyle of the rich and famous.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra