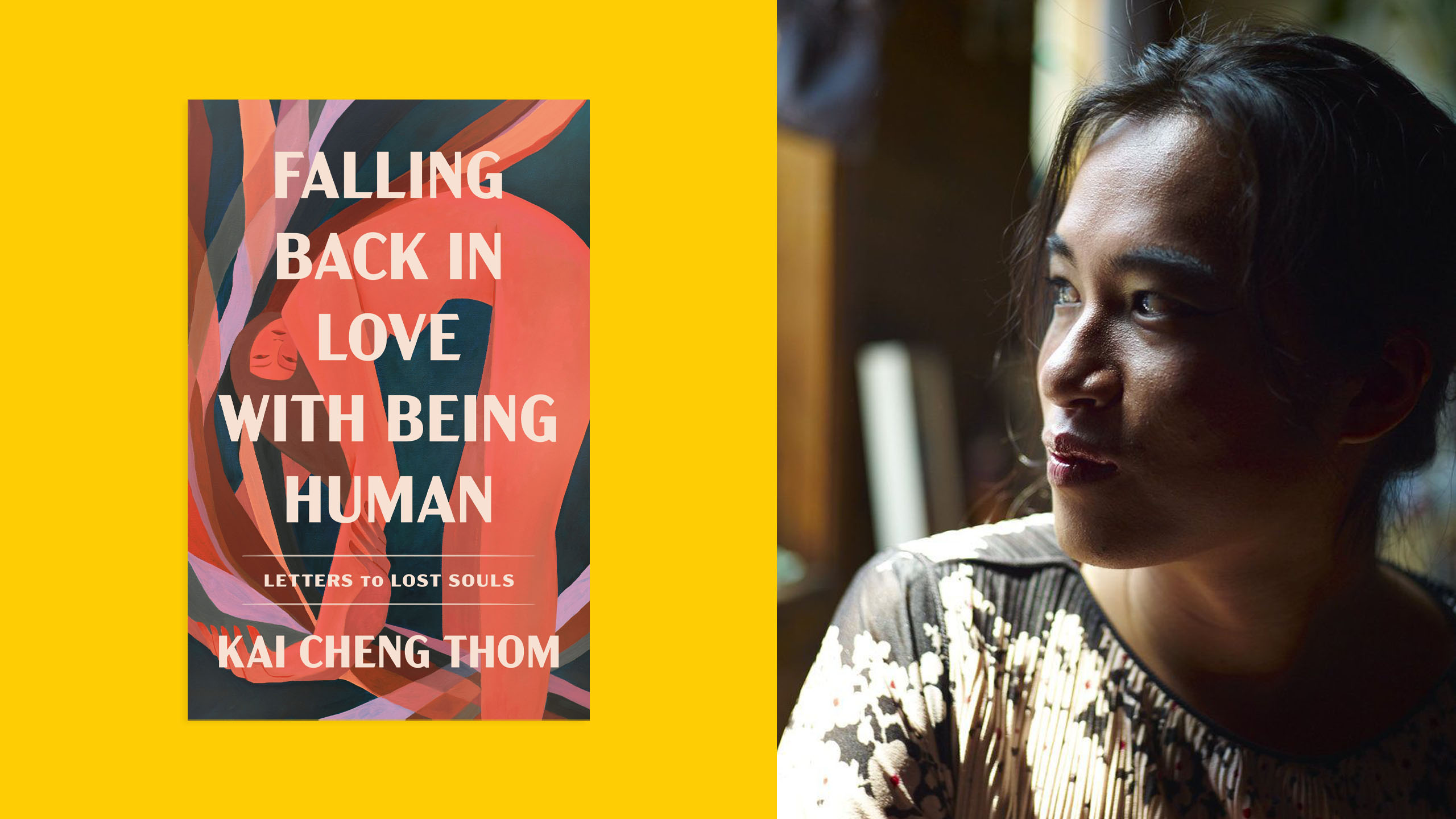

Although Kai Cheng Thom’s latest book, Falling Back in Love with Being Human, was just released last month, it’s already become a Canadian bestseller. The book, formatted as a collection of love letters, was written largely during the early days of the pandemic and it shows: each letter is thoughtful, intimate, compassionate and quietly profound.

As the editor of Xtra’s Ask Kai column, I recognized many of the book’s themes as ones Cheng Thom has been exploring in her writing for years, from harm and forgiveness, to faith and learning to love oneself better—and so I was excited to speak with her about her latest offering. We sat down to chat about writing love letters, the steady rise of anti-trans hate and how to find love in a world that so frequently feels like it’s completely on fire.

This book is not the first one you’ve written, and previous books have taken different forms, from essay collections to a novel to a children’s book. Why did you choose to format this book as a collection of letters?

In some ways it’s shocking that I didn’t write an epistolary collection before now because I love the letter format. I’ve always loved it, ever since I read The Color Purple in school. I think there’s an immediacy to letters and particularly to the love letter—an immediacy and an intimacy. That particularly comes from writing in the second person. There is nothing more specific than writing directly to somebody or something.

When I wrote this collection, we were in the middle of the first wave of the pandemic, and we were going through a whole societal exploration of DEI [Diversity, Equity and Inclusion] and anti-racism. There’s something about the rawness of that time I think, that really, really called for the directness of the love letter.

Are you a big letter writer in your everyday life?

Yes, sometimes to my detriment. I quickly learned that the love letter is such an intimate and intense form that it’s not one that everyone wants to receive. When I first started writing letters, they were to boys. It would be in the stage of dating where you start to notice someone isn’t answering your messages as often. When you write a letter to someone in that position you generally don’t ever hear back. I think sometimes people feel it’s a lot, or they don’t know what to say.

I’ve also been in that position. I hope she won’t mind me saying this, but Kama La Mackerel—writer and performer extraordinaire—and I dated for a while about 10 years ago, and when she broke up with me, she broke up with me by love letter. It was by far one of the nicest breakups I’ve ever experienced, but I never wrote back—her letter was so loving and tender and I was 19 and I didn’t know what to say. When I started writing this book, I actually went back to my old email account and found her letter and wrote back. We’ve been friends for a long time and she’s now my literary translator, so the experience was very touching and funny.

Love letters are also interesting in a specifically queer and trans context. Up until recently the public could mostly only determine someone’s gender and sexual identity once their private diary entries or letters ended up in archives.

That’s true, I hadn’t thought of that. It’s kind of sad to think about how, if queer people are writing love letters—which I think we’re doing less—they’re being written over text message or email. And as we all know, some platforms like Google delete our data if our accounts are inactive for long enough. The archives of queer letters and queer love are gonna be lost. I worry about that.

The title of the book is quite evocative. How did it come about?

The original working title of the book was Thirty Love Litanies because the religious aspect of the book was much larger in my mind when I started writing. But Thirty Love Litanies doesn’t really pop as a title. When Penguin Random House picked it up, my dear, sweet editor Dave Ross was like, “This is great, but also I’m not sure everybody knows what a litany is.” And I was like, “That’s fair.” So we went hunting around for a different title.

“Falling back in love with being human” is a phrase that’s lifted from the introduction of the book. It really is just the spirit of what the project is. I’m writing love letters not from the perspective of already being in love, but from the perspective of being brokenhearted and trying to find my way back.

Faith is something that comes up a lot in the book. Can you tell me a bit about what faith means to you?

Oh, God. There are two layers of it for me. One is the religious side. I was raised evangelical Christian. Being an evangelical, Christian, Asian queerdo is, like, a particular experience. One of the interesting and difficult parts of that experience for me is that I never fell out of love with Jesus. When you’re evangelical, Jesus is your number one. He’s your boyfriend. Whenever you need something, you know, you’re supposed to look inside and look for the love of Jesus. And I just really liked that when I was a kid. Jesus was also the first depiction of an unclothed man that I saw. So I was very confused about the whole thing—feeling the love of Jesus, but also you’re not allowed to be gay. And I think that that still makes its way into my experience of the world and definitely this book: I still really love that concept of a messianic figure who gives us gentle love even when we have sinned.

There’s also the non-religious angle, because, truthfully, I’m not Christian anymore. So I spend a lot of time thinking about what we have to believe in when we’re no longer, say, evangelicals. I think what a lot of people end up having faith in is community or other people. And the thing about community and people is, just like Jesus, eventually they break your heart—but we can keep loving them anyway. That’s the kind of faith that I’m going for in the book: modelling oneself after that idea of grace. Even if it’s not religious, it’s still worthwhile.

The concept of loving people after they’ve hurt us comes up a lot in this book as well. Your last book and your Xtra advice column also frequently touched on the topic of how to forgive or love for people who have been socially exiled for their bad behaviour. Why is this topic of particular interest to you?

I think it goes back to how I was raised. I connected with the concept in Christianity of forgiving the unforgivable. When I was a kid, I knew I was a gay weirdo extremely early on. Christianity told me there was something wrong with me, but it also told me that Jesus could forgive anything. That paradox of being unforgivable, but also having hope for forgiveness got kind of locked into my soul very early on.

As an adult, I see themes mirrored in conversations around community. Both Christians and queers are obsessed with right-doing and wrongdoing and who belongs, who does not and purity. All of these things are embedded in queer culture—it’s just a different flavour. And I think what allows us to let go of our suffering and be in healthier communities with one another is leaning into this idea that the unforgivable can still be loved. I’m not the only person who, as a little child, internalized that I was inherently bad. And I think it is that belief in inherent badness that then comes out in us as adult queers and causes us to perpetuate lateral violence against one another or against ourselves. We have to learn how to be in love with the parts of ourselves that we don’t like in order to live.

Some of the letters in the book are addressed to specific public figures—like J.K. Rowling—who have made public anti-trans statements. Why did you choose to engage, however indirectly, with those parties?

That’s probably one of the more controversial aspects of the book. Most queer people I talk to will be like, “Yeah sure, okay, let’s love all queer people, even if they’re bad, whatever.” But some of the letters are written to transphobes or TERFs. If I’m writing a love letter to J.K. Rowling, is that dangerous or harmful or, like, inherently kind of assimilationist? Am I in some way condoning her behaviour or public remarks? I don’t think I have a clear answer to that.

I think I do have this obsession with whether it is possible to connect with people who are doing harmful things to me and, if so, can we find some kind of transformation through that connection? Even as I’m saying this I’m like, “Oh my God, how many shitty boyfriends have I had?” We know it doesn’t necessarily work that way. Except that I’m also a transformative justice practitioner and I know that it sometimes does work that way. Sometimes the miracle is possible. The edge that I am exploring with this book, and also in my life is, what is it that makes a miracle possible? I’m not ready to let go of that hope. Because I think when we let go of it, a really important possibility vanishes from the world.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately in the context of anti-trans backlash. I’ve watched it grow in recent years and sometimes I struggle to understand just how it got this bad. I keep trying to imagine how we turn the tide around, and sometimes it feels impossible. But I think you’re saying that to you, it feels possible?

I think we’re caught in this dialectical cycle of abuse and defence. The abuse is obviously coming from transphobes and then the defence is coming from us. What happens in an abuse-defence cycle is that the abuser perceives the defence as abuse, right? This is true in very intimate situations, and it’s true on a societal level: when a trans person shows up at a protest and is rightfully loud or angry, transphobes are like, “Look! Violence!”

I think every trans person in the world right now has the right to be angry and defensive, you know, in the way that they need to be to survive. But I also think that if we could actually connect with whatever the fear is, on the transphobic side, then maybe they could begin to perceive us as human. It just sucks to have to be, like, the people who are proving our humanity. Nobody should have to do that.

Finding that connection is the interesting dialogue, to me. Not the dialogue of debate. It’s really about saying to the other side, “You are the people with the power. You are the people who are being driven by fear. I am not going to be driven by fear. Why are you doing this to me?”

That’s a hopeful position to take. How do you maintain hope?

I mean, sometimes I don’t have the hope. Let’s just be real.

But no, honestly, it’s queer people that give me hope. It’s funny because we’re special because we’re queer and trans, but also we’re a microcosm. We can be so mean to each other and so disillusioned—but also I wouldn’t be the niche celebrity I am now if there weren’t for a fair number of queer people who want to believe in what I’m saying. My work has put me in touch with people who have done harm, witnessed harm, experienced harm. And having come through that, they’ve decided that they want to be in relationship with people in a different way. Queer people are always looking for ways to rehumanize each other and themselves. That’s what really lights my fire and keeps me going. I do actually witness people pursuing goodness.

If there was one thing that I wish any reader could walk away from this book with, it would be a little bit more capacity to love oneself. Not in the selfish validation of one’s own bad behaviour. I mean a true ability to see how one’s actions are hurting other people—but with enough self-compassion that we can think about those actions and try to change our patterns. I want people to leave this book feeling more love for themselves, for the purpose of trying to be better.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra