It may take a village to raise a child, but it takes a right-wing leader feeding the pages of a children’s book into a paper shredder to freak out a nation’s progressives. In fact, the gesture was seen as so nasty that it pushed a book of fairy tales about characters and relationships of various genders, orientations and ethnic backgrounds up the national bestseller list, with publishers around the world snapping up the rights to translate it.

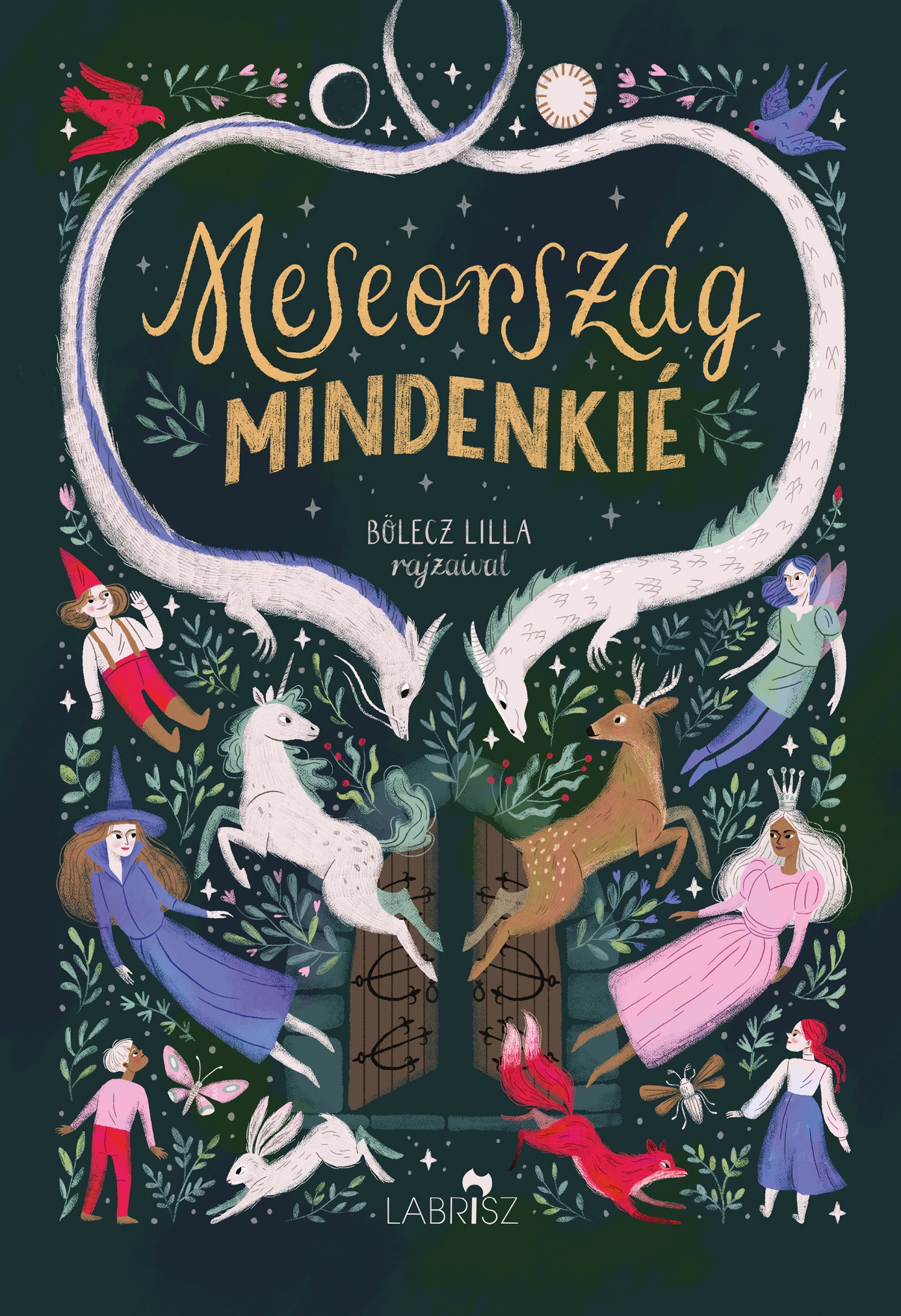

Sounds like a fanciful David and Goliath story to read at bedtime, but that’s what happened when the Hungarian lesbian group Labrisz published the book Meseország mindenkié (A Fairy Tale for Everyone) last September through its educational program. Seventeen emerging and established artists contributed stories and art that reimagined classic fairy tales through a diverse lens: there’s a deer who wants antlers, a Roma girl who unlocks magic by saving the tiniest creatures in the world and a prince who falls in love with another prince. Intended for use in classrooms, it was the seventh title released by Labrisz since the group was founded in 1999. Their first book sold 1,500 copies, a typical circulation. Yet Meseország mindenkié has already sold 30,000, with its first press run selling out in two weeks. So far, Labrisz has sold the rights to publishers in Poland, Sweden, the Netherlands and to HarperCollins in the United States.

“Somehow, the book became a symbol of protest against this oppressive system. It’s actually become one of the largest cultural events of the last year,” says Dorottya Rédai, a board member of Labrisz and project manager for Meseország mindenkié. “We have become a bit more independent, so we won’t depend on grant applications all the time for the next few years.”

Since Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and his populist-conservative party Fidesz came to power in 2010, LGBTQ+ Hungarians have felt like they have targets on their backs.

Just this week the country’s parliament passed a law which prohibits sharing information about LGBTQ+ people or about “gender change” in schools or in media aimed at those under 18, including advertising. The vote on the law, which also provides a list of organizations approved to teach about sex in schools, was boycotted by some opposition parties, and prompted protests in the streets and criticism from human rights organizations.

“On this shameful day, the opposition should not be in the parliament, but in the street,” Budapest mayor Gergely Karácsony wrote on his Facebook page.

Though Orbán has not yet rolled back the relationship registration system for same-sex couples that had been introduced by a previous, more liberal government, he has restricted adoption to married couples (registered same-sex couples and singles no longer qualify) and changed the constitution to define marriage as only between a man and a woman (it also further defines a “father” as being a man and a “mother” as being a woman). In a law passed last November, children were also given the “right” to be raised according to the gender they were assigned at birth, making it difficult to support or provide services to trans and gender-diverse children.

Another law, passed last spring, took away trans people’s right to change their name on legal documents. That law was passed under the auspices of the state of emergency declared because of the COVID-19 pandemic. “It had nothing to do with COVID-19, obviously, but now you cannot change your name and your gender in your official documents anymore,” Rédai says. It took a recent court victory to prevent the law from being implemented retroactively, so trans people who already had started legally changing their names will be able to finish the process.

Orbán seems to be borrowing many of his tactics from Russian President Vladimir Putin, the master of demonizing certain groups to consolidate power and weaken opposition to increasingly authoritarian rule. The new law against “promoting” LGBTQ+ people to minors resembles Russia’s 2013 law against “propaganda against non-traditional sexual relations.” (Poland, too, has been following this trend, says Rédai, though both countries have historically had very different relationships with Russia.) For example, during the peak of the Syrian refugee crisis in 2015, when millions of Syrians were fleeing a civil war at home, Orbán talked about refugees as public enemies, says Rédai. Although many refugees passed through Hungary, few stayed; that panic slowly evaporated, and Orbán had to find another group to attack.

“Government officials started to give really shockingly homophobic speeches: they started to conflate LGBT people with paedophiles and they started this discourse that children have to be protected from LGBT people,” she says. The law that more strictly defined “mother” and “father” also introduced harsher punishments for sexual abuse against children. “They put together paedophilia and homo- and transphobia in the same law. It’s really a trap because if you criticize this law, then you will be [accused of] supporting paedophilia. Opposition parties cannot say anything about it because we have elections next year.”

It was amid this flurry of anti-LGBTQ+ legislation and rhetoric that Meseország mindenkié was shredded by Dóra Dúró, the deputy leader of the far-right nationalist party Mi Hazánk. Though the party does not hold any seats in Hungary’s parliament, her dramatic protest against “homosexual propaganda” brought the book wide public attention.

The government’s consumer protection authority told Labrisz that the book needed a warning about “patterns of behaviour deviating from traditional gender roles” appearing in a book, which purportedly violated the rights and interests of consumers. Though Labrisz did pre-emptively tweak the blurb on the back cover for its second print run, they refused to add a warning. “Do we want to put a sticker with ‘Over 18’ or something on it? No way. No way,” Rédai says. “We are actually suing the consumer protection authority because [the demand] was unlawful. We are waiting for the court case to go on.”

The shredding prompted left and middle-of-the-road Hungarians to rally around the book. “On the one hand, there is stronger homophobia than before, but on the other hand, people who are against the government and think in a more liberal and tolerant way, they are much more supportive of LGBT people and rights than before,” Rédai says. “People who never spoke out on these issues were so shocked by what’s happening and how unfair it is. Celebrities who never said anything before stood up and organized story-reading events.”

After opponents of the book harassed salespeople in bookshops that carried the book, supporters brought the workers chocolates and flowers “and tried to support them emotionally.”

Rédai said Labrisz could never have predicted the controversy the book set off. She says the latest round of laws targeting LGBTQ+ people would have happened whether Meseország mindenkié was published or not (it was unclear at press time how the new law would affect the book’s availability).

She’s curious to see how the translated versions of the book will do in other parts of the world. “It’s a different cultural context, so I don’t know how it will work in English-speaking countries,” she says. “But there will be a lot of good royalties, which is important for us as a grassroots organization.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra