Derek McCormack has attracted a cult following with his sparse and darkly comic books that, even when they’re not directly referencing carnivals, talent shows and fashion runways (which they usually are), read like pageants of the grotesque. Garments and the people who have designed them always loom large, as do obsessions with the disgusting and shocking. In The Well-Dressed Wound, the 2015 novel McCormack wrote while being treated for a cancer which, he says, spread inside his body “like moss,” Belgian fashion designer Martin Margiela declares, “If there’s anything that faggots love more than death, it’s fashion…. The walls have AIDS!…. The chandeliers have AIDS! The mirrors have AIDS so all the reflections are the same: AIDS!”

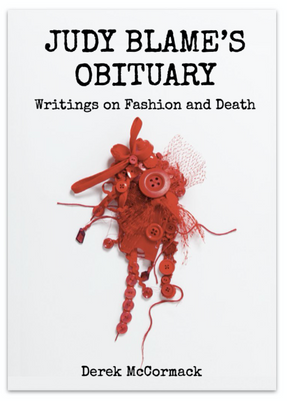

While publishing these outrageous fictions over the past 26 years, McCormack has also been doing his own quirky take on journalism—essays, interviews, reviews—for publications like Artforum, The Believer, Werewolf Express and, weirdly, Canada’s National Post newspaper. The best of these pieces have now been compiled into his latest title, Judy Blame’s Obituary: Writings on Fashion and Death, named after the late punk-inspired U.K. stylist who worked with Neneh Cherry, Boy George, Björk and Kylie Minogue. Though the essays appeared in a variety of publications over a couple of decades, they come together in this collection as a timeless, cohesive whole—probably because McCormack’s way of thinking about the world is nothing if not consistent.

McCormack isn’t shy about asking novelist Edmund White about his friendship with Yves Saint Laurent (“very drugged and drunk and just out of it”), inspecting clothes worn by outlaw writer Kathy Acker or interviewing sculptor David Altmejd about jewelry.

I talked with McCormack by telephone from his Toronto home.

A lot of people write about fashion, but mostly it’s advice on what to wear, what not to wear, who’s wearing what at which party. But you dig right into fashion’s place in the human psyche. When did you become so obsessed with fashion and its connection to death and, as you regularly remind your readers, homosexuality?

Just as a little kid, I loved fashion. I was very aware that it was faggy to love it and that the act of loving it was troubling to adults around me. I never thought of becoming a fashion designer or going into fashion, probably because I have no talent for visual things. I couldn’t even do line drawings well when I was a kid. Making sentences seemed to be the only thing I had any skill at at all. A lot of my love of fashion got solidified with music when I was a teenager because the bands I liked had looks, you know? I started buying Vogue when I was a teenager. I would buy it secretly at the bookstore in downtown Peterborough, where I grew up, and they’d put it in a paper bag like it was pornography, and I would put it in my coat and take the bus home. I remember very well the issue where Japanese designers Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto first appeared in Vogue and seemed to me very, very thrilling because they seemed so antagonistic and explosive. I would read The Face and i-D magazines, which I bought at record stores. All these things came together. In terms of homosexuality, listening to the music I did was considered faggy, the way they dressed was faggy. It was all a big faggy package. I don’t think I realized until I was an adult that there were straight people in the fashion business. That came as a surprise to me. This was all reinforced by the terrible gay stereotypes at the time, like in Mad magazine, where you’d see these limp-wristed effeminate characters talking about fashion and wearing cravats. I know it was supposed to be laughable, but I loved all that. That’s what I wanted to be, a scary homosexual. That was always my goal. I failed though.

How did death become part of this formula?

I don’t know about you, but when I was growing up and people called you a fag or beat you up or kicked you out of class or whatever, they’d always be like, “You’re dead, you’re fucking dead.” The threat of violence made me realize, “Yeah, I might be dead already or I will be dead shortly.” Then I remember going to my GP [general practitioner] when I was a teenager and I told him that I was gay. And he said, “Well you have to get an AIDS test.” I said, “I’ve never had sex with anyone.” He said it didn’t matter. I don’t think that was an uncommon experience for gay men at the time. Definitely, that solidified the thought that I was married to death. And there’s a long discourse in history about how fashion and death are related: fashion’s always dying, fashion’s made to die. The corollary to that is that fashion is frivolous, forgettable, disposable. I suppose that I thought being gay meant all those things as well. But I didn’t take that as bad. I thought if all of this is troubling to the world, it must be good.

There’s a line running through the book about how fashion, tapping into human vanity, also taps into our destructive tendencies. How certain fragrances require harvesting certain animal parts, which seems particularly cruel, or how stylish clothes can cause discomfort and pain. You make fashion seem so macabre.

I think discomfort is a really important theme in the book. How does one live with discomfort? How does discomfort make me more alert? How does discomfort make us different? I’ve always been interested in how discomfort can derange me or change me or deform me. I’ve never been interested in healing it or fixing it. The 25 years I’ve been publishing has been an exploration in how perverse I can push myself to be. Fashion is an industry that actually thrives on perversity and novelty, and getting darker and weirder. I love that. I envy that.

Do you own any fashion yourself? Do you consider yourself a fashionable person?

Oh, fuck, no. I’m too poor and too slovenly to be fashionable. People who hear I wrote a book about fashion are just going to be in utter disbelief: “This sloppy old guy would dare do that?” I go out with toothpaste on my shirt, salt stains on my boots and a tear in my pants.

Your fashion writing covers everything from underground cult figures, like Judy Blame, to the costumes that Nashville singers of yore used to wear. Do you have a favourite era or favourite approach to fashion?

I have a ton of nostalgia for the late 1970s/1980s period where I learned what fashion was and I learned that I loved it. I’d start with Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren, then go up the street to Margiela in the late 1980s. That said, I love just about every period of Paris fashion. I’m a fashion Francophile, one of those people for whom Paris is heavenly. I’ve only been there once. It wasn’t heavenly, but in my mind, it’s paradise.

Your essay on a museum exhibition of the work of Manfred Thierry Mugler is both an insightful review and a kind of prose poem: “There are vamps, shedevils, glamazons. There’s a chimera in golden armour and sequin scales. There’s a fish woman in a fishtail gown with fins. There are women who appear to be wearing parts of Cadillacs—dashboards, fenders, lights—or who appear to be themselves Cadillacs.” Mugler passed away earlier this year, so I wanted to ask you what set him apart from other gay fashion designers.

He was a super important designer, but he had never been my favourite. Of the big three at that time in Paris—Mugler, Claude Montana and Jean Paul Gaultier—Gaultier was my favourite. He was sexy in a more surprising way, more literary, and I liked the men’s wear, those kilts and those backless tops. And with Mugler, I liked all the men’s wear, but really, everyone looked like they were in some version of Star Trek. All of those designers started with very little. They were just super talented and they were aces at constructing and cutting. They worked their way up, from selling a few things at boutiques to putting on major shows. That story is impossible now, so it seems so romantic to people. Fashion is such a big business, and it’s become so dependent on social media, I think there’s the sense now that you don’t even have to know construction in design to be a fashion designer. You hire people to do that and you brand it or conceptualize it. So I think that the nostalgia for Mugler is that he did it all. He conceptualized it and he made it. The shows he did with Gaultier and Montana were huge shows involving hundreds of models. There was a sense that someone can start in their mother’s sewing room and become a world-famous designer.

There’s a lot of talk these days about the joy of wearing clothes, embracing what’s comfortable, wearing what you feel like wearing, rather than buying into something that’s someone else’s artistic expression. Does that bug you?

Yeah. Well, I think fashion is a force that incorporates everything. Everything becomes a look. Comfort becomes a look. Looking like you’re exposing yourself becomes a look. Looking like you don’t care about fashion becomes a look. One of the things that interests me is how the mood of the moment can shift on a dime. Suddenly, we’re in another era; when a subculture bubbles up from the underground and, suddenly, what’s right for the time is different. I love those moments and they always happen. They’re regular. So it doesn’t bother me what people wear, although I think it is really a hippie moment right now; people are comfortable wearing a bit of everything. That will change.

In the book, you make references to having had cancer. You were diagnosed more than a decade ago with what started as a tumour in your appendix, which then spread to other parts of your body. Your treatment was long and intense. Some writers might write about their journey and all that they learned from the diagnosis, treatment, recovery. Not you. You write a chapter about insufflation—a medical procedure where medication is blown inside the body—and compare yourself to an inflatable balloon, then riff on the history of special-occasion balloons, jack-o’-lanterns, pigs, dragons. It’s both comic and horrifying.

I was such an idiot. You know, you get cancer and you’re pretty much guaranteed if you write a book about it, you get good reviews. I totally fucked it up. During the cancer I wrote a really angry, disgusting novel [The Well-Dressed Wound]. I never thought about writing that journey book, because I could not. The whole process of being sick has been so disgusting that it’s really bleakly funny most of the time, because what else can you do but laugh when there’s stuff oozing out of every part of you? I remember when I got diagnosed with cancer, my friend said, “Oh my God, this must be the happiest day of your life.” They weren’t right, but they were pointing at something true because I had always talked about death, and death had shown up. In my fiction writing, it’s shown up as a sort of urgency. When I wrote The Well-Dressed Wound, I was mostly confined to bed. I didn’t know if I was going to live, but I thought, “Oh, I’m going to finish a book,” which is so stupid when you think about it. But when you’re really sick, it’s not like you can go hiking in the Alps or you suddenly have money to do exotic things. What I did was let it all out. I let out whatever anger I had, whatever rage and fear. What I went through was a series of humiliations. They were necessary. But I just thought: I won’t hold back on any of that, and I certainly won’t sugarcoat it. I certainly refuse to find a rosy ending or a journey of wisdom because there was too much anger, too much madness, too much sadness. I didn’t find peace at any part of the process, so I didn’t pretend that I had. I love the thought of deforming my writing, deforming my mind. And sickness did that. I could feel the illness changing my brain, I could feel it changing me and not always in good ways. I didn’t fight it. I just thought: let’s see what kind of person I am after this. In that way, cancer was like fashion. I just let it remake me. I submitted to it.

How are you feeling these days?

I feel pretty good. I’ll be 10 years from surgery this spring, which is incredible to me. My body’s pretty worn out; the surgery worked well, it just took its toll.

Reading the essays, I started out wondering when and where they were originally published, who the presumed audience was and the broader context of each piece. But then because your style is so distinctive and your interests are so interconnected, the book pulled together as a whole for me. So I’m wondering what you notice looking back on this work that you’ve produced over so many years?

It turns out I’m an obsessive writer. I just keep going back and going back. If you’re a magazine or newspaper editor and you ask me to write something, you can probably tell in advance what I’m going to give you. It’s weird in a book to have three essays about the same artist. But I’m happy with the way the book turned out because it shows that I became a better writer over time, that I was thinking about the same things for decades and maybe just now I’m coming to figure out what they mean to me. There are probably 10 essays in the book which were published in the National Post, which is a loathsome newspaper, but I had such good editors. As a small-town kid who dreamed of the glamour of fashion writing, writing some of those pieces was a confirmation for me. I’d get flown to New York to go to a party or see a show. There’s hardly any print media left, and I don’t think that those fashion houses care about flying reporters anywhere anymore. They want influencers, TikTok stars.

What are you working on now?

I’m working on a short novel that reads like an art catalogue, and while I’ve been writing it, I’ve been making the art—jewelry objects—that go along with it. I’ve never done anything like it before. I’ve never made stuff before so I’m very shy about it. If you read my books, it’s not that big of a surprise because books are filled with objects, whether it’s sequins or jack-o’-lanterns. Now I’m trying to produce the things I write about. Or illustrate my fiction. We’ll see. It might be terrible.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra