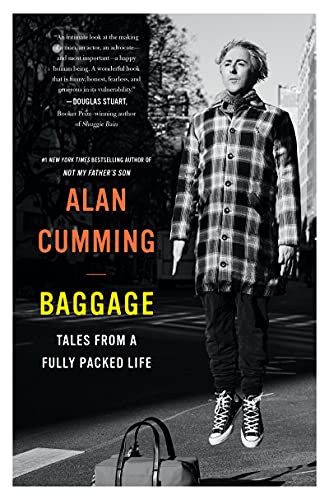

“I try to advocate for positivity and optimism and kindness,” says Alan Cumming. The multi-talented queer icon is calling from New York City minutes before the Big Apple launch of his second memoir, Baggage: Tales from a Fully Packed Life. “I try to encourage people who have hatred and negativity and bigotry to open themselves up to the things that they’re scared of. And hopefully, they won’t be so scared to begin with anymore.”

Uttered by a pop psychologist, a life coach or a lesser talent, this tidy summation might ring false. But Cumming—who spends the bulk of Baggage unpacking the messy years between the collapse of his first marriage to actress Hilary Lyon and tying the knot with American illustrator Grant Shaffer—delivers heaps of similar proclamations in this dense and dizzying autobiography. Fortunately for readers, these ideas are presented as conclusions gleaned from hard-won experience and not as feel-good formulas for success.

“You’re probably going to have bad times and bad days and be a hot mess,” Cumming explains during our brief call. “Sometimes, that’s totally fine. I think, especially in the United States, we love a redemption story. And we’re not very good with things being messy. We like it all to be tidied up.”

“There I was, this sort of little pansexual sprite being absolutely lauded for being kind of a deviant.”

With its enormous cast of characters and lightning-fast segues from one anecdote to the next, Baggage is anything but tidy. Cumming opens the memoir by questioning the role of memory in recall and growth; he compares his life experience to a pot of boiling spaghetti and memory to the spaghetti drained through the colander of his brain. This cheeky metaphor sets the tone for an irreverent retelling of personal and professional highs and lows, spanning the years 1993 to 2006.

The memoir also flashes back to Cumming’s brief career as a teenage journalist and photo-story model, as well as his time as half of the comedic duo Victor and Barry. Cumming also revisits the horrific abuse he endured growing up in Scotland, which was the subject of his first memoir, 2015’s Not My Father’s Son.

In dealing with abuse—or the past in general—Cumming says, “You’ve got to be constantly vigilant. You’re never fixed. You’re never, never over it. It’s not a triumph, it’s not a thing that you can achieve, and that’s the end of it. You can come to terms with something, and it is still going to possibly come back.

“And so, I’d say to people it’s unhealthy to think of it as something you’ve conquered.”

A prolific actor, director, singer, writer and activist, the genre-defying Cumming has shared stage and screen with everyone from a chimpanzee named Tonka (in the 1997 family comedy, Buddy) to former U.K. prime minister Tony Blair (at a 1997 New Labour rally in Edinburgh). There’s plenty of name-dropping and behind-the-scenes dishing in Baggage, and it’s mostly—but not always—flattering.

In a touching reminiscence about the 1995 Goldeneye premiere (Cumming played nerdy hacker Boris Grishenko in Pierce Brosnan’s first run as James Bond), the actor recalls his mother, Mary Darling, hobnobbing with Tina Turner (who sang the theme song) and Dame Judi Dench (who played M). At first, the scene “did not compute,” but he remembered that the three women were of a similar age, and realized that his working-class mum had finally come to accept “her rightful place at the table” at her son’s showbiz events.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, Cumming recalls spending a weekend with his boyfriend at Gore Vidal’s Italian villa and watching the drunken literary giant verbally spar with Howard Layton, Vidal’s partner of over 50 years. He describes the septuagenarian Gore as a bitter old queen who showed him kindness as a prelude to cruelty when discussing Cumming’s work on a semi-autobiographical novel. After being admonished for trying to hold his boyfriend’s hand at the breakfast table, Cumming analyzes his hosts’ behaviour and sexless relationship. He sadly concludes there was no place for love, tenderness or touch “in a home two men had shared for 30 years.”

While Cumming names celebrities, he protects the privacy of lovers who have become close friends or have proven to be mistakes. He writes tenderly of a woman who proposed to him and with whom he shared an L.A. flat filled with rented furniture. He speaks candidly about the sexual chemistry with a boyfriend whose name he tattooed on his abdomen and the couple’s regrettable decision to spend the New Year’s Eve of the millennium at Dollywood (Dolly Parton’s Tennessee theme park). He also tells of a lover and friend he met on a flight from Newark to Austin who introduced Cumming to his future husband, and whose offer of a post-9/11 getaway led to the actor buying a cottage in the Catskills Mountains a week after the terrorist attacks.

A good chunk of Baggage is devoted to Cumming’s star-making turn in the 1998 Broadway production of Cabaret. A remount of the Sam Mendes-directed London production, it introduced Cumming to New York audiences. At a time when the U.S. was embroiled in the Bill Clinton sex scandal and the country was debating whether oral sex was intercourse, Cumming’s lascivious emcee was a slap in the face to the puritanism that had taken hold of the nation.

“I was being sexualized and objectified,” Cumming says about his Cabaret role. “And I was a man projecting a sort of pansexuality. I think that was a reaction against prurience and what was going on with the government, and how sexuality was being shamed. And then there I was, this sort of little pansexual sprite being absolutely lauded for being kind of a deviant, as it were.

“It was a reaction to what America was seeing on TV news everywhere. I was projecting all this shameless sexuality. And I think that was a big counterpoint.”

That performance established Cumming as an artistic force in New York, a city he fell in love with the second he saw it. Cabaret brought a who’s who of NYC society and showbiz royalty to his dressing room door; it also led to a Tony win, which Cumming describes as “much more a relief than a triumph.” New York embraced him, and Cumming embraced it back. The city is very much a character in Baggage, holding an equal place with the people who stole his heart or triggered his ire.

“I think people who have never belonged anywhere feel they belong [in NYC] and form this really interesting tribe of misfits.”

“I think people come to New York because they’re different. If you’re different where you come from, when you get to New York, you realize it’s full of people who are different.” Cumming explains. “I came here and was lauded for many of the things that I was derided for in London: my difference, my Scottishness, my sexuality and my values.

“It really felt like home, not just because I was lauded, but because everyone here is kind of different, even the people from here. So, I think people who have never belonged anywhere feel they belong here and form this really interesting tribe of misfits. That’s what New York gave me: a sense of belonging.”

Baggage condenses a lot of life into its 268 pages. Cumming travels the world, acting, singing, dancing, loving, meeting new people and having nervous breakdowns as he constructs, deconstructs and reconstructs his identity. The narrative moves at warp speed. The breathless Cumming pauses to offer pearls of wisdom like, “I found peace but not closure” about his abusive father, or to poke fun of himself as a “sex symbol in the primate world” when revealing the tragic fate of his chimpanzee co-star, Tonka.

Baggage sometimes feels like a succession of elaborate set and costume changes, but it never comes across as inauthentic. “You have to project authenticity if you’re a performer,” Cumming says, referencing his friend and hero Liza Minnelli. “It’s about being your authentic self and being a showman at the same time. I think that’s what she does so well. I’ve learned from her.”

But what can more pedestrian readers learn from Cumming, a performer who never seems to stop moving?

“You have to structure your life so you can have those times when you can completely let go,” he says, signing off as the book launch approaches. “I have a lot of focus in life. Right now, I’m completely focused on you. And then, in 10 minutes, I’ll be completely focused on this event. At some point in the evening, I’ll be completely focused on getting stoned and letting go. I don’t think that there’s any conflict. I think it’s really important to organize your life to have some abandon in it.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra