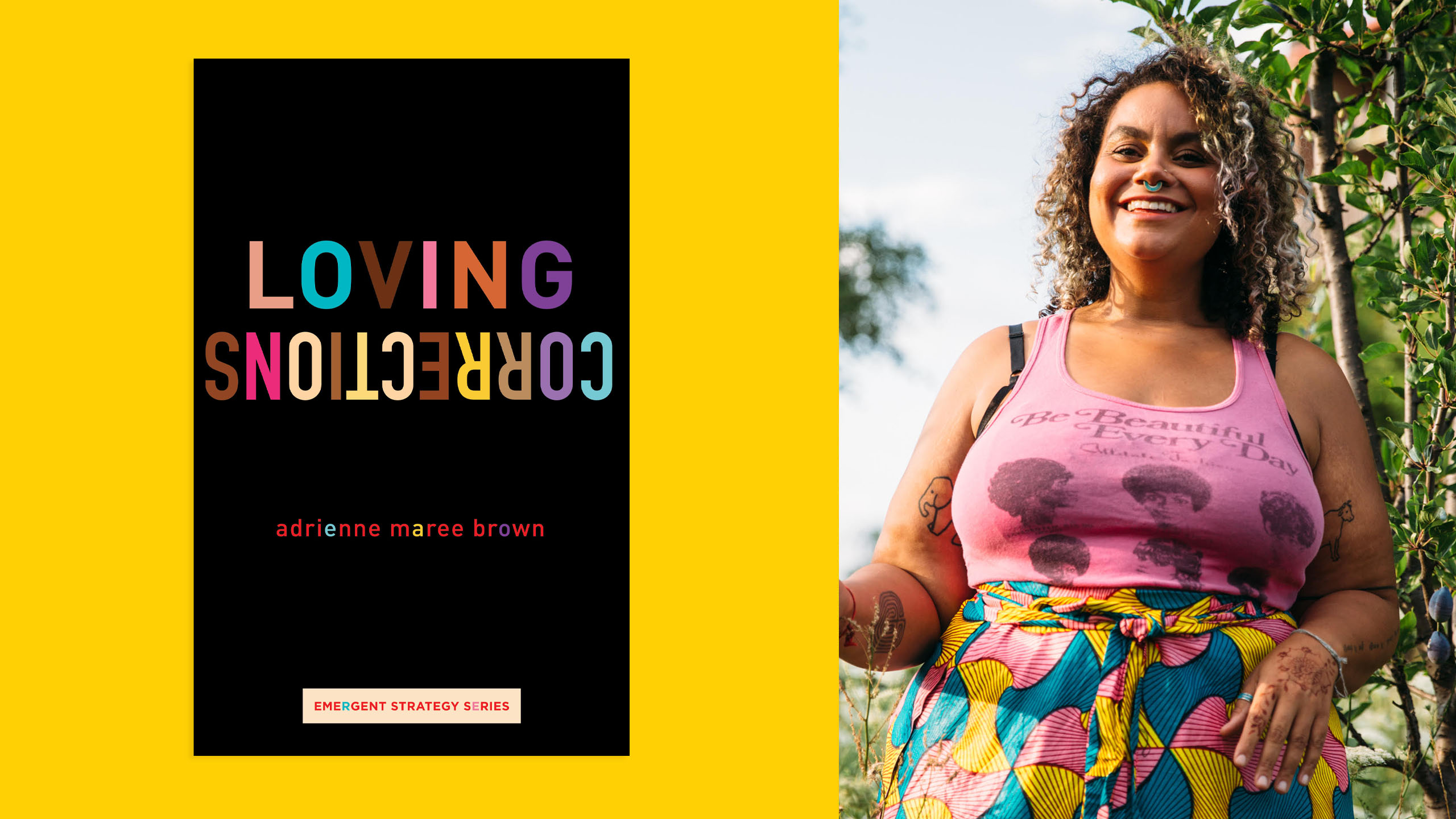

How do we respond to conflict in new ways? Is there a way to address small bugaboos before they turn into conflict? How do we give each other helpful information and feedback in order to move into a more loving and free future outside of carceral logics? In her new book, activist, facilitator and author of Emergent Strategy and Pleasure Activism adrienne maree brown wants to tackle these questions.

brown has helped us to practise the future together through speculative fiction, reconnect with ourselves and our pleasure and joy, and shared with us how to build movements that are emergent and thriving though her past literary offerings. In this new work, Loving Corrections, she offers us tender care and loving course corrections for a world on the brink of massive change. I sat down over video chat with brown in July and chatted about her new book, her favourite tree and the possibility of love-based “course correction.”

What is Loving Corrections, for those who are new to this offering?

[The title of] Loving Corrections is [referencing something] literal! It’s really the act of saying, “Oh, I have something that feels like a correction with someone I care about or with some people or some group that I really care about, and I want to make that correction in the most loving way that I can.” In the sense of course correction, as we’re on a journey together and the way we’re going is taking us at odds with ourselves and Loving Corrections puts us back on the path toward love, toward each other. And it’s rooted in my facilitation style.

For years, people would be like, “There’s something you do when you facilitate where you’re able to just get us together, but it doesn’t feel like you don’t like us or don’t respect us. What is that?” In a lot of my writing, I’m facilitating that same energy of trying to say, “I see your humanity. I’m holding your hand and I’m going to tell you something that we already know about whiteness or about masculinity or about Zionism or about connection.” The book is full of essays where I’m actually doing that activity and also different kinds of pieces that show some of where I learned this approach from.

What would you suggest to folks who are hoping to practise new, better, ways of relating to each other through conflict, crisis and harm?

There’s this whole spectrum of questions and answers—what is transformative justice? What is abolition? How do we stay in relationship with each other? What role does cancellation play? What does accountability look like? And I feel like the Loving Corrections piece is the practice of intervening when you need to, so that you don’t end up down the road in some situation where you’re feeling like, “Well, shit, there’s no possibility of relationship now because I didn’t say what I could say when I could say it, or I didn’t say it in a way that you could hear.” I’m thinking about timing. I’m thinking about the relationship, the respect that comes in. Here’s a practice of being able to see someone that you love and to accept them, right? I deeply accept that you are who you are and I believe that you can change, and I hope that you deeply accept me as I am and believe that I can change toward the good, toward being a better member of the collective of our species. When I’m in a relationship with someone where I’m thinking, “I don’t even believe you can change and I don’t even care,” then that’s not where this practice makes sense. If I totally disrespect you, then that’s going to come through in how I speak, it’s going to come through in the points I try to make.

With loving corrections as a practice, the fundamental aspect of it is that I believe that you can change. I believe we are all constantly changing and growing. The book contents are full of things that we know. These are things that in movement spaces, we kind of take for granted or default. We already know some of this stuff. So how do we practise knowing that in a way that’s not looking down?

“With loving corrections as a practice, the fundamental aspect of it is that I believe that you can change. I believe we are all constantly changing and growing.”

There’s a whole conversation with my siblings. I wanted to show that because I’m interested in what it means to be in relationship with people for life. I think in some ways, accountability, managing conflict and addressing harm are different when you’re thinking, “I’m not letting go of this relationship. I want to find the best possible manifestation of this relationship in this lifetime.”

I think there’s a lot on social media that people think is accountability, and they think is a loving correction. And I wanted to offer a different river we could travel. The way that we do stuff online ensures that there’s no humanity. There’s no sense that “Oh, my words might have a real impact on your sense of self. That is not the impact that I want to have.” Most conversations that really are meaningful don’t happen online. We can build community in specific spaces online, but if I really need to be gathered, I need someone to sit down with me. I need someone to get on the phone with me. I need someone face to face with me who can go through the messy.

In person together, we may have to say a thing, walk away and come back. We may have to make intentional room for this. And you’re not going to say what I scripted in my head. You’re not going to say what I predetermined is your stance. You’re going to be a human coming into it and I’ve probably hurt your feelings already, or you’ve probably sensed that I’m holding some judgment or something. It’s going to be messy. And what I wanted to do is provide permission to be messy and to learn to do this in a way that actually allows us to stay connected to each other, because I don’t think we can actually afford to keep letting go of each other with such ease and such glee.

What you’re offering is such beautiful medicine. It’s rooting us in what we can offer when we are our best selves. There are so many reasons why our gifts get downplayed, which is part of how we end up in conflict with others in the first place. I’m curious about this idea of turning toward each other even in a moment of toughness as a way of medicine, maybe even ceremony.

I think of everything as ritual right now. I wonder “What are the rituals by which we stay in connection with each other?” And boundary-setting is a ritual to me. I want to be in relationship, but I need to be able to have an honest conversation. I think a lot about honesty, and not honesty that harms. What is honesty that still cares for the person in front of me? So that feels really big.

When I wrote We Will Not Cancel Us, it was like, “Boom, we won’t do it.” And then Holding Change to me is the book that’s like, “Here’s how we actually can facilitate together, and particularly, there are mediation skills.” Now this book asks: before we get to the place where we need mediation, we can do this other thing called loving correction, where if someone’s in a meeting and they say something, and it’s someone you care about and they blunder into white supremacy or they blunder into patriarchy or they blunder into something that’s like, that’s not where we are at. Or they say something that doesn’t attend to the fact that we are in a climate catastrophe already. It is like, okay, that blunder has happened. Now, how do I move in and sit next to that person and ask, “Where was that coming from for you? Do you know about this? Would you be willing to read this together? Would you be willing to think about this differently? And here’s what I feel, here’s how it impacts me.”

When we think about what is the practice of this, it’s really that we come a little closer in these moments rather than addressing conflict by pulling away. I’m going to let technology get in the way. We often say, “Oh, I’m so busy.” Nobody’s that busy. Nobody’s too busy for the people they care about, so I think about that too.

This might be a larger lifestyle of loving correction, I’ve really right-sized the number of relationships in my life because I’m like, if I can’t have accountability and we can’t do this love and corrective process, I probably shouldn’t be investing majorly in this relationship. And I’m like, oh, I can have 20 to 30 people at significant depth in my life.

“How do we take responsibility for being alive at this time? What are the things that our ancestors already worked on and figured out, that we’ve got to steward through to the next generation?”

You write about the future a lot—and about “practising the future.” In what ways is this book preparing us for what’s coming?

I have been thinking about the intersection between survival-prepping and just being a person and my value system. I want to make sure that I have neighbours who are truly neighbours, who know that they can come to my house and I can go to their house. If stuff hits the fan and the power goes out and someone’s shooting or whatever, then I know places I can get to without any instruction, without any GPS. I know places I can go and I’ll be loved and I’ll be received. With my immediate neighbours around, I’m just making sure that I know your face, I know your name. I know you have a dog, you have two dogs, there are two dogs on one side and one dog on the other side. If something happens, I’ve got an eye on, okay, we need to make sure the dogs are okay. We need to make sure the people are okay. We need to make sure.

How do we take responsibility for being alive at this time? What are the things that our ancestors already worked on and figured out, that we’ve got to steward through to the next generation? Even if we go through a repressive period, we already know that trans women are women. We already know that white people are racist. We already know these things, and we have to steward that knowledge through in a mycelial way. So for me, this feels like the way the mycelium gets activated. It’s like, oh, I have this book. I can give it to my uncle who’s showing some racist tendencies and just be like, “Just read this,” and let’s talk about it.

There’s a whole conversation I have with my sisters about how we have made sistering a practice and an activity and a verb for us. A lot of people are in families where they’re like, “I just don’t even know how to be in my family anymore,” especially when there’s difference present.

We have a model that’s actually working pretty well for us. One of my sisters works for the State Department. One of my sisters is a radical organizer goddess teacher. One of my sisters has dogs, one of my sisters is a cat person. We have differences, you know what I’m saying?

So we sit down, and both with my sisters and with my family, and we’re like, “What do y’all think about what we just saw? What do you think about what’s happening?”

The movement shaping that I received was to actually be pretty harsh with my corrections, and to be very exacting and not really leave a lot of space for the humanity of the other people, because I had the right theory in my mind. I’ve been trying to figure out what is the softest way to be a revolutionary? What is the way that I can do this that is truest to myself, Venus and Libra, love goddess, self, that is also still inviting people toward their own liberation. And that’s the other piece around loving corrections—I’m not trying to correct you to serve me. I’m trying to get you on the path that best serves us, all of us.

What did you learn writing this book that surprised you that you might want to offer? Was there anything that you’re like, “I didn’t even know that was going to come out, but it did”?

One of the pieces [that surprised me] is about smoking weed. I love marijuana. I have always loved it. It’s been the medicine that works best for me with my anxiety, with my pain, with everything else. I realized, “Yeah, but we can’t all be high at the meeting,” and that I needed to write about that. I need to say that on behalf of facilitators everywhere and on behalf of the communities we serve who are not served when we step out in the middle of a meeting and get so high that we can no longer actually participate well.

So that surprised me! As a harm reductionist, and as someone who is pro-cannabis and pro-legalization, now we’re in a different phase where as things get legalized, we have to be more mindful about what we’re doing with them. Alcohol is legal, but you would never sit in the middle of a meeting and just be like, “I’m going to drink until I can’t participate.” So, that was a surprise to feel that and to realize that it’s okay to say that.

How does life and love of the planet tie into these Loving Corrections?

I think the main thing that we’re supposed to be doing on earth is trying to live and really putting effort toward life. That’s the lesson I always get from nature. All of this matters equally. Prentis Hemphill through the Embodiment Institute has been posting these gorgeous videos. Prentis has been a good teacher for me. When I landed in Durham, I was like, okay, I’ve been living in Detroit in an apartment on the second floor in a little box, and I don’t really know how to be in nature. And I am moving somewhere now where I have a garden and I want to do this. And Prentis was like, “Get to know the tree in your backyard.” They said, “There’s a tree. What kind of tree is it?” I said, “Oh, it’s a red maple.” Prentis said, “Okay. Go talk to it. Listen to it.”

Now that tree and I have a deep relationship. Most of my spirit work happens with that tree. When I wanted to buy my home, I took my menstrual blood and did a ritual with that tree. Whenever anyone in my life is transitioning, I lay out flowers and I ask the tree to help soften the path of that transition, whether it’s from life to death or anything else. Change is happening and you know how to go from the root to the stars, so can you help? And the tree is so helpful and so vibrant. And now a squirrel is nesting up in its branches and I’ve got bird feeders hanging off the tree and it’s just become like this … it’s my own little sacred tree of life.

Finding a tree that you can befriend and that you can be in ceremony with is helpful. You can lean your back against this tree. Some people wonder, “How do I be hugging a tree? People are going to see me.” To that I say, “Just lean against it for a moment.” People think you’re just waiting and they don’t have to know that you’re actually doing a little ritual with the tree. And then looking up, wherever you are, a patch of sky will do you good.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra