Credit: Paul Gallant

Hola, dear readers! I’m Paul Gallant, contributing editor at Xtra, taking my first ride on the “Topline” train. Although I’ve been helping edit the culture section here for just a couple of months, my history with Xtra goes back to 1999, when I moved from Vancouver to Toronto to take the job of features editor. Yes, I’m that old. I still have collections of DVDs, CDs and books… and maybe even a few cassette tapes in boxes somewhere. Boxes I haven’t opened since I left Vancouver.

Although I’m a text kinda guy, I’m probably hanging out amongst the pretty pictures on Instagram more than I’m lurking on Twitter. Yet chatting with you right here in “Topline” is also a lovely place to be, an opportunity to look back at where we’ve come from and look at where we might be headed.

But remember, “Topline” is just to whet your appetite—don’t forget to subscribe to Xtra Weekly to get the full newsletter and the tasty all-sorts it contains.

What’s the buzz 🐝?

Forty years ago this week, on June 5, 1981, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published an article in their Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report about a rare lung infection found in five young, previously healthy men in Los Angeles. Two of the men had already died by the time the report was published.

That short article in a publication for specialists foretold a coming crisis.

“The fact that these patients were all homosexuals suggests an association between some aspect of a homosexual lifestyle or disease acquired through sexual contact,” the article reads—clinical words to mark the beginning of an epidemic that cut a scar through our community. Correction: that is still cutting through our community.

First called GRID (Gay-Related Immune Deficiency) before eventually being given the name AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome), what we now call HIV or HIV/AIDS was still a mystery in the summer of 1981. Prevention, treatment, cure? Those questions were far in the future. Researchers were still making guesses at what it was, how it spread and how it affected the human body. The fact that gay men were the group first identified as being at risk for the disease made it an uncomfortable issue, to say the least, for governments and institutions that, back in the 1980s, didn’t like to talk about sex, never mind gay sex.

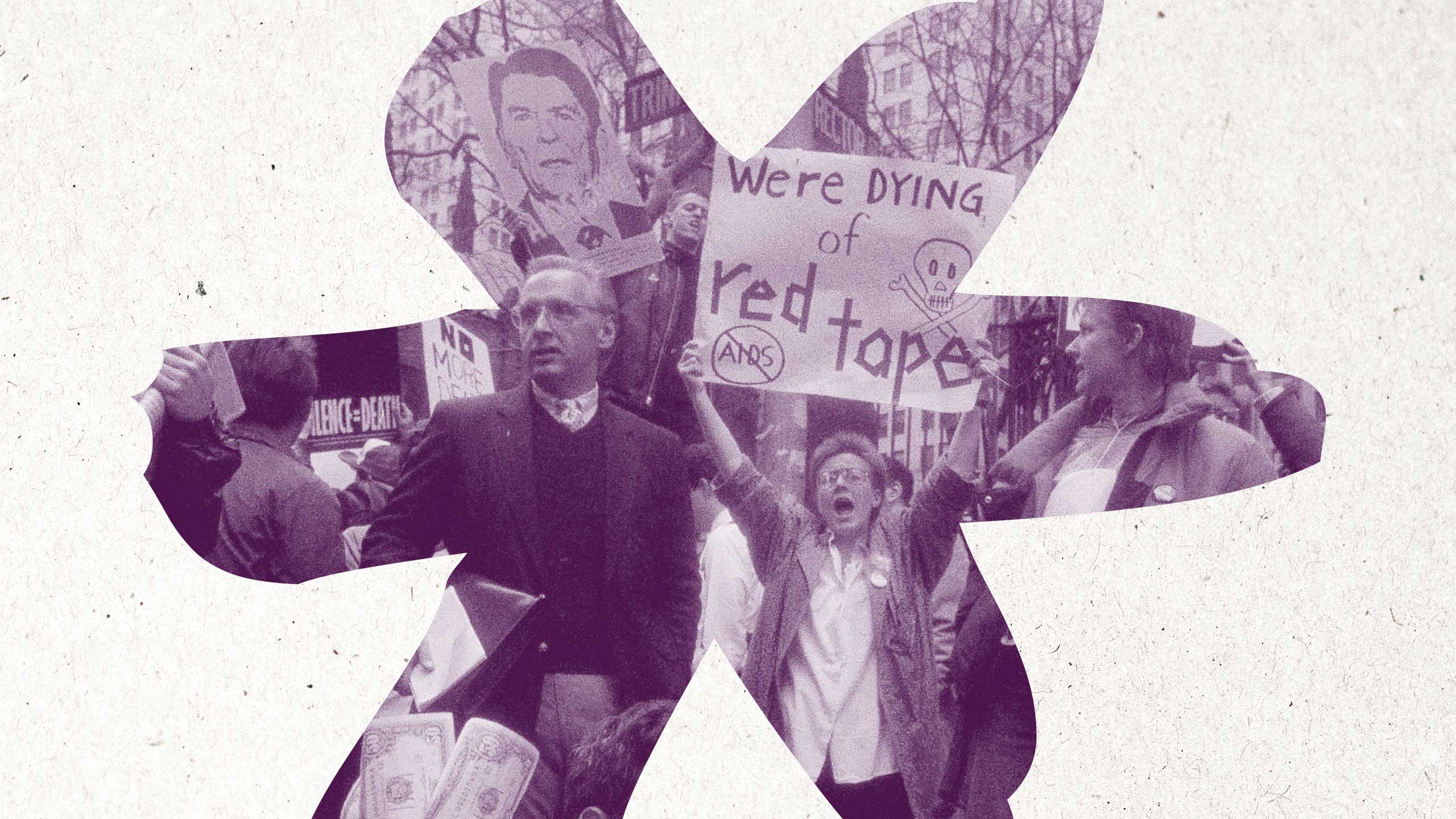

This summer at Xtra, we’ll be covering the dark anniversary of the beginning of the AIDS crisis with a variety of stories that examine the epidemic’s impact and our community’s resilience in the face of what, in the summer of 1981, was an unknown threat.

What were we thinking 🕯️?

I had my first argument about AIDS in 1987 with the co-editor of my high school yearbook. We were two teens living very sheltered lives in rural Prince Edward Island, but we had strong opinions. I wouldn’t realize I was gay until years later, so the debate was not personal—not yet, not consciously.

The argument was over a year-in-review collage of things cut from newspapers and magazines. I wanted to include a tabloid headline about Liberace dying of AIDS in February 1987. Liberace, it’s true, did not seem like a particularly relevant inclusion. He was not who we listened to; he was not even our parents’ music. But he was the most famous person since Rock Hudson to die of AIDS. My co-editor worried that her grandmother, who was in Liberace’s target market, would notice the headline and be upset by it, since it was sad and also implied, according to what we knew at that time, that the closeted music idol was gay. We compromised by running a clipping without Liberace’s name: “Desperate battle with AIDS —.” I imagine now that I insisted on the inclusion of the puzzling dash because I wanted to call attention to what was not being said. Little did I know how little I knew.

It is hard for young people now to realize how taboo a topic AIDS was and how tied up it was with the taboo of homosexuality, though the recent TV show It’s a Sin is a helpful primer. I recently read Sarah Schulman’s new book, Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993, before I interviewed her for this story, which we published last month. I was first struck by the fact that these people were fighting for their lives and being arrested for their cause while I was still years from losing my virginity and coming out. In 1987, I had no idea ACT UP existed, but their actions—for example, their innovative poster campaigns promoting safe sex—would eventually shape me, shape my view of sex, shape my sex life, shape how I view government’s role in public health and what I think of the pharmaceutical industry. Today’s LGBTQ2S+ community has the fingerprints of early AIDS activism all over it, whether we know it or not.

The other thing I thought of, reading Schulman’s book, was how slow progress was back then. AIDS was on the radar of the medical community by 1981, but the first serious treatment, AZT, was not approved until March 1987. At the time, it was considered a miraculously speedy process. Ultimately, AZT was not a panacea—its side effects could be brutal, and it wasn’t effective over long periods of time; mostly, it was buying people an extra year or so of life. By the mid-1990s, AZT was replaced by the more sophisticated antiretrovirals that are used today to keep HIV-positive people healthy and keep the virus at untransmittable levels. Back then, suffering people waited almost six years for a drug that was, essentially, half-baked. Many died waiting. By the end of 1987, between 5 and 10 million people were estimated to be living with HIV worldwide.

Think of that when you consider how multiple COVID-19 vaccines came to market less than a year after the virus was discovered. Think of the political will and the capital it took to make that happen, and the brilliance of modern science. Think of that when people are wary of vaccines that are more than 70 percent effective. What we can learn from the first few years of the AIDS epidemic can help us through the rest of COVID-19.

In other Xtra news 🌎

👉Chanelle Gallant (no relation to me… that I know of) asks all the right questions about how growing police budgets have failed to reduce the amount of sexual violence in our societies, and examines solutions that are emerging from the movement to defund police.

👉I didn’t watch a lot of TV in the early aughts, but I still got pulled into Thomas and Tranna’s debate about the revival of 2000s culture, a trend that’s picking up steam just as many millennials are turning 40. I guess I’m not the only one who didn’t get what he wanted out of Friends.

👉As someone who stumbled upon Alison Bechdel’s Dykes to Watch Out For in alt weeklies way back in the day—I’m talking before the popularization of the term “the Bechdel test”—I have been amazed at how the cartoonist has kept her unique voice while becoming a publishing juggernaut.

👉Although I’m no longer a religious person, I always admire people who find the liberating messages, often ignored or stamped down, that lie at the heart of many religions. Berlin-based Seyran Ateş is one of them.

👉Getting ready to hit the dancefloor in the post-vaccination era? Emma Glassman-Hughes’ piece on dancing on her back porch, and the songs she namechecks, will get you in the mood.

👉Want more headlines? Subscribe to Xtra Weekly.

Gifbox

Fighting the good fight can feel like a party.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra