In the opening scene of Nicola Dinan’s second novel, Disappoint Me, Max, a 30-year-old Chinese British trans woman, spots a younger white woman dancing at a New Year’s Eve house party. She takes note of the woman’s miniskirt and bra made of chains, and the way she’s dancing “completely out of time to the music,” and deems her the type of woman that no one would ever think was trans. But Carla, a friend of hers who is also trans, soon corrects her. The younger woman in fact transitioned at 13 and is now a model. Max is shocked and deflated at this news. Having just come through a rough breakup, she is coming to terms with no longer being in her twenties. “I won’t always be beautiful,” she thinks, with some dread. Moments after this, she falls down a flight of stairs. Though she is relatively unharmed by the accident, it propels her into a quest to tone down the partying and try to find a relationship that is less toxic than her last one. She soon begins dating Vincent, a handsome, pragmatic lawyer from a strict Chinese family, who is straightforward and kind; however, there are secrets he harbours from his past that could threaten their relationship, and upend Max’s own sense of self.

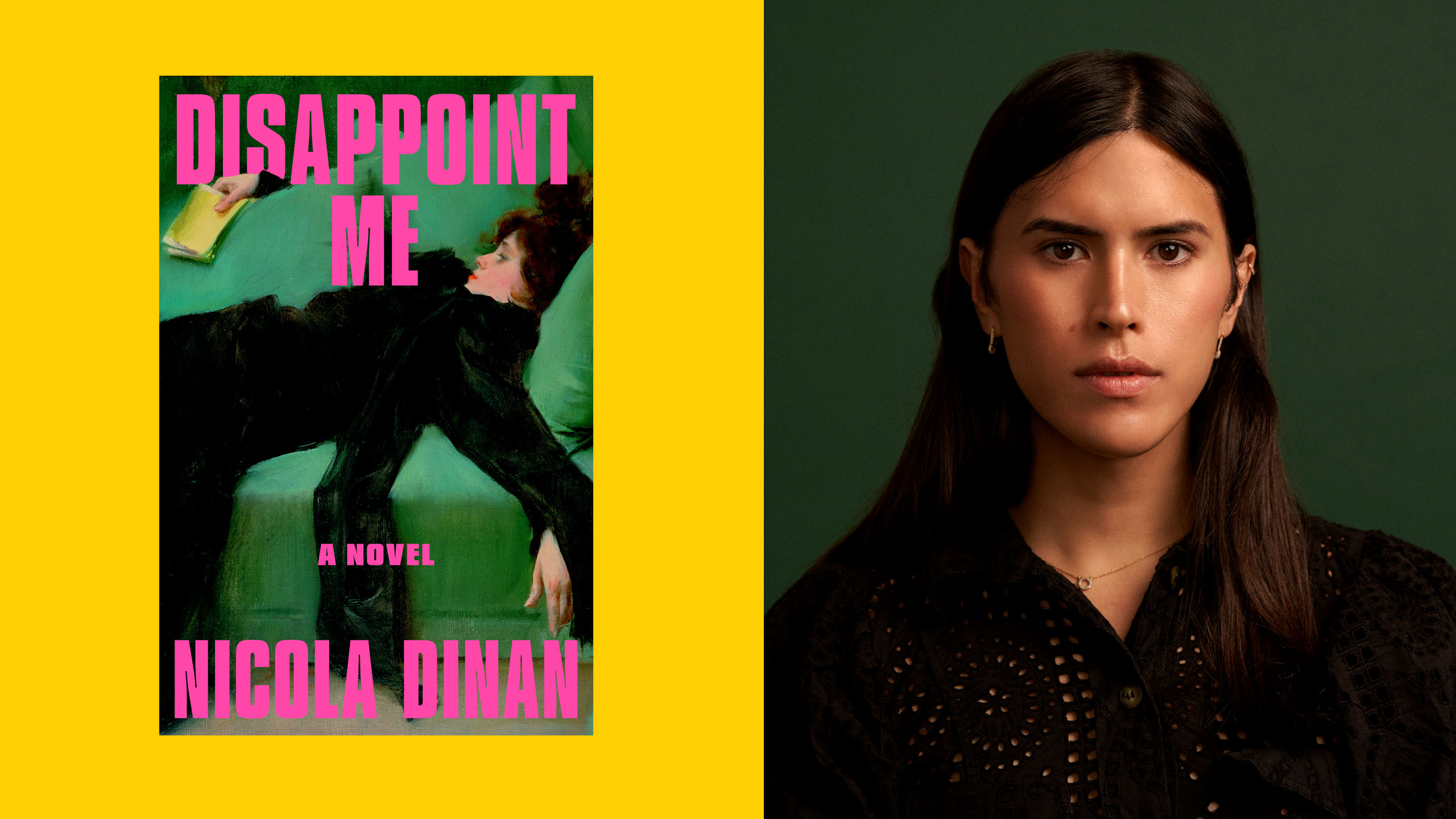

Disappoint Me is Dinan’s follow-up to her debut novel Bellies, which won the Polari First Book Prize in 2024, and was a finalist for several other awards, including a Lambda Literary Award. Bellies centres on a romance that at first appears to be between two university-aged boys; the heady relationship is challenged when one of the two comes out as trans. Disappoint Me is similarly concerned with the intimate emotional details and nuances of romantic relationships between trans women and cis men; here, Max’s transition is not a focal point, but her transness does mean that she is always questioning and second-guessing the true intentions and desires of the men she dates. Dinan is mixed race and grew up between Hong Kong and Kuala Lumpur; she now lives in London. Her stories and characters reflect a life of moving between places and languages, as well as contending with transness.

Disappoint Me is composed of two related narratives that unfurl along different timelines: the main timeline brings us to London in 2023, and is narrated by Max, short for Maxine; the secondary timeline takes place in Thailand in 2012, and is narrated by Max’s future boyfriend Vincent, during his gap year between high school and university. Both timelines are anchored by romantic relationships, and by the emotions and tensions that these couplings elicit. In the 2023 timeline, Max and Vincent meet and start dating; their rapport is more warm than passionate, but Max is wary of what passion can lead to. During an early date with Vincent, Max reflects: “For many years, it’s been hard to separate love from anxiety, from push and pull.” Vincent seems to be a safer, kinder choice than her past boyfriends, and their blossoming relationship, though not without strife, is sweet and nuanced, a dance of mutual respect and understanding. However, in the 2012 timeline, we come to learn about a violent incident in Vincent’s past, involving his best friend Fred and a young trans woman named Alex, that puts this sweetness into a more ambiguous light.

It is worth noting that the 2012 sections, narrated by Vincent, are often tauter and more engaging than Max’s sections. This isn’t necessarily because of the violent incident, which Dinan writes with sensitivity and attention to its painful repercussions; it’s more so because of the deeper sense of risk and urgency that Vincent feels throughout his time in Thailand. Being out in the world alone for the first time makes him more keenly aware of what he desires, what he lacks and the lengths he will go to in order to fit in with people like Fred, or the anonymous white bros at the hostels he stays in. Vincent’s is a story of self-betrayal, interpersonal betrayal and their fallout. Max’s story is a less compromising one of trying to belong in a cis, straight, bourgeois world, one that she would fit quite comfortably into if not for her transness, due to her own upper middle class, white-adjacent position. Her trajectory has its moments of dissonance and stress, but doesn’t involve the level of self-interrogation or reckoning that Vincent’s does.

Disappoint Me is a fun read on a scene level. Dinan is especially adept at writing the funny, painful particularities of mixed-race families, relationships and friend groups. In 2012, Vincent is painfully self-conscious, having grown up as one of the only Asian people at school, in the shadow of Fred, who is white, handsome and confident, though secretly depressed. Arriving solo at a hostel in Thailand, Vincent performs a particular type of male Britishness, shouting “You all right, mate?” in a booming voice—a phrase he’s never uttered before. He feels guilty for caving into racism, but is determined not to get treated the way his parents do, with their Chinese accents that “match their faces.” Elsewhere, Max’s mother provides comic relief. She is the half-English half-Chinese daughter of wealthy parents, and grew up on the Peak, Hong Kong’s richest neighbourhood; she only learned to speak Cantonese in adulthood, but leans into her Chinese heritage in an exaggerated manner that makes Max, who is a quarter Chinese, cringe. When Max brings Vincent to visit her parents, who now live in Scotland, Max’s mum begins speaking to Vincent in wobbly, over-enunciated Cantonese. Max thinks, with some spitefulness, that she looks like “a white person doing a racist imitation of a Chinese person.” Max’s mum likes to hold forth about the systems of medicine and knowledge that “we, the Chinese” have developed, all of which Max also finds embarrassing, especially in front of Vincent, whose whole family is Chinese, and from a much more modest Hong Kong neighbourhood than the Peak. Perhaps though, some of Max’s cringe toward her mother is that of watching someone try to step into a persona that doesn’t quite fit them; Max often worries that her transness is a conversation topic for others, especially when she tries to fit in with straight people. She fears that Vincent’s straight friends and her own high school friends look down on her because she isn’t able to get pregnant. “Is everyone thinking about my lack?” she wonders in one scene, as everyone around her discusses babies and parenthood.

Dinan sets up various tensions between characters, or between characters and their circumstances: Max shows up at a friend’s book reading only to find that her difficult ex is giving a reading as well; Max’s father committed a grave lapse in judgment when Max was young, an incident that the family rarely speaks about in the present; Max’s best friend Simone, a lesbian who works as a model scout and agent, gets publicly outed for her unprofessional and manipulative work emails to the young women she represents; Max is asked to be a bridesmaid at her aggressively straight high school friend’s wedding and has to contend with feelings of inadequacy around gender and heteronormative rituals. However, these tensions are set up only to be defused quite quickly. Even a medical emergency that throws Max’s life into crisis midway through the novel is integrated into the narrative in a way that feels oddly unruffled. This might be because Dinan’s characters, especially Max, are eminently reasonable people who tend to lead with compassion, rather than vindictiveness and dramatics. While it is admirable to behave this way in real life, it doesn’t always lead to the most compelling narrative on the page.

At one point, Max reflects on her tendency toward compassion, in situations where she has been wronged: “I wonder if accepting moral complexity is a sign of my poor standards … my desperation for love and belonging and for care.” She then wonders if it could be the opposite: that because she’s been through pain, she has a deeper understanding of the pain of others and why that pain might cause them to act selfishly. The trouble is that we don’t actually learn much about Max’s pain, other than the broad strokes of it. Her last boyfriend wouldn’t commit to her. She feels sad that she can’t bear children, and is understandably triggered when straight women point this out. On the one hand, it is refreshing to read novels like this one, with trans women as main characters who do not have to suffer inordinately in order to be worthy of protagonist status. On the other hand, Max’s difficulties are, though realistically and thoughtfully portrayed, written in a way that does not allow the reader to get into the existential muck with her. As a character, she is prone to feeling upset and then almost immediately reasoning her way out of the upset. Feeling both judgmental and out of place at her friend’s heteronormative wedding, Max allows herself some catty remarks to Simone, but quickly pulls herself together: “Maybe I really am just a hater. Emily is a nice girl, and it’s really quite sweet that she made us bridesmaids.” She and Simone have always bristled at being called “nice,” but now she wonders whether she shouldn’t try being nicer. Similarly, while Max is initially shocked at Simone’s leaked work emails, by the cruel side of Simone that they reveal, the incident does not lead to any real reckoning for Simone, or for the two women’s friendship. There is nothing wrong with Max’s tendency to excuse other people for their missteps; but it has the effect of distancing the reader from Max’s uglier feelings, which, if allowed to percolate more, might allow us to feel closer to her, to share in her existential anxieties.

Dinan smartly structures the two narrative threads of Disappoint Me so that the consequences of the 2012 timeline spill out in the 2023 timeline, in a culminating scene near the end of the novel. However, even here, the drama is somewhat muted, as by this point, nothing that is revealed in the multi-character blowout is of any surprise to the reader, who is already aware of the secret that is being shared with everyone. Dinan is a sharp, observant writer, and Disappoint Me presents big questions about forgiveness, justice and responsibility, about whether people can change after they have done bad things to others, and what sorts of misdeeds we might be willing to accept in our friends, family members and lovers. At its best, it invites us to ruminate on these issues through the detailed perspectives of its characters, whose varied viewpoints allow us to examine the major events of the novel from different angles. The abundance of compassion that Dinan has for her characters, and that they have for each other, is laudable, even if not always the most exhilarating fodder.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra