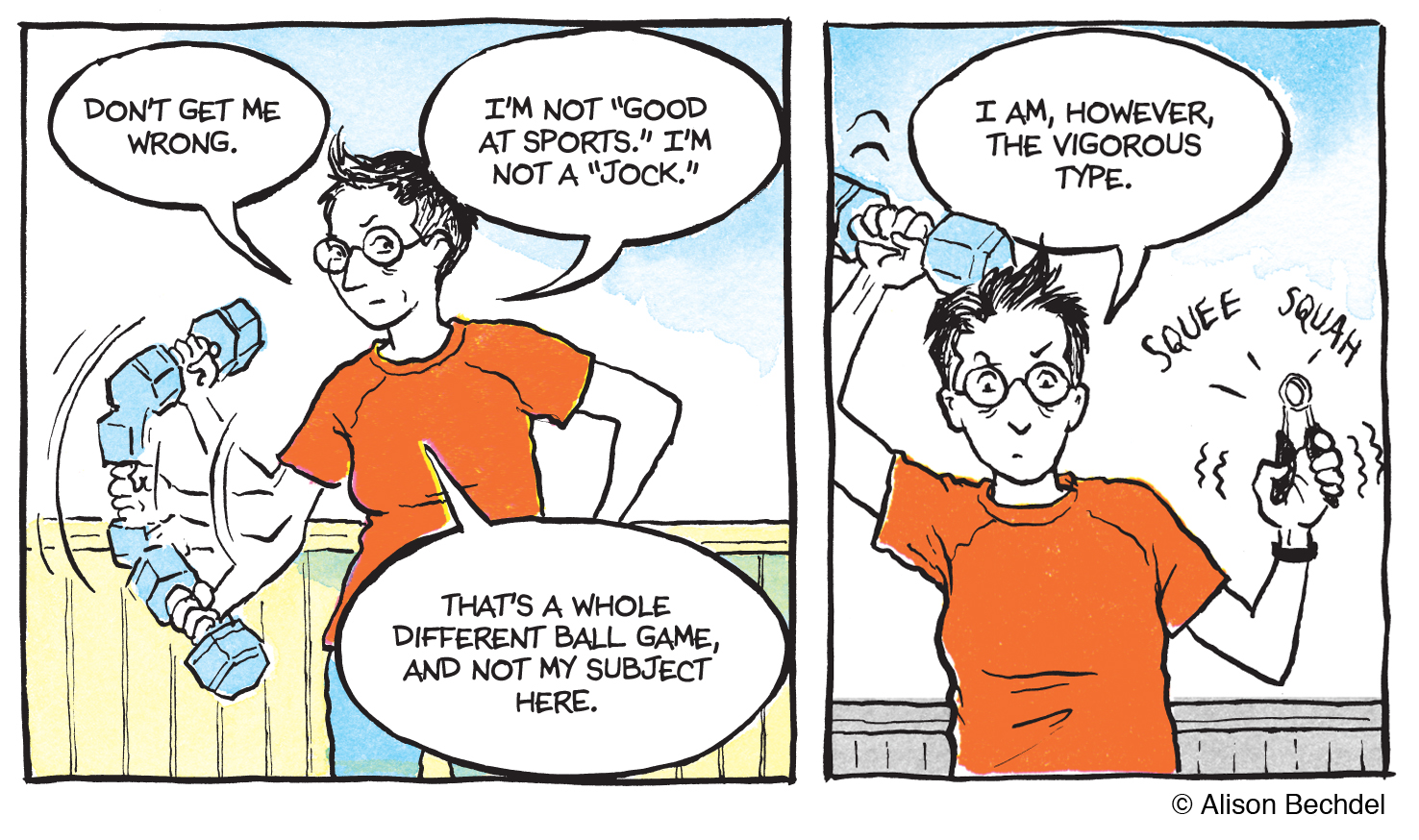

For cartoonist Alison Bechdel, making comics and pursuing physical exercise have many parallels: obsessive hard work, repetition and advancement, physical and mental stamina and bodily damage.

Both her passions require specialized and fetishized equipment, and she usually performs them alone. And though her labour and expertise have brought her many great rewards, she struggles with ambivalence: Are the comics good enough? And what’s the point of physical fitness if we’re all going to die anyway?

Bechdel’s comics once belonged to queer women, but over time her audience grew larger and more diverse. From 1983 to 2008 she wrote and drew the serialized comic Dykes to Watch Out For. Her graphic memoir, Fun Home, was about her closeted father’s suicide, and later became a Tony award-winning musical; it’s been optioned for film starring Jake Gyllenhaal. She followed that book with Are You My Mother?, a memoir about her relationship with her mother. Bechdel’s life has become fragmented into multiple narratives—the actual life she lives, her version of it in comics, another interpretation in the musical and as a story that nestles in the minds of readers and audiences. Through her many works, her lesbian perspective has subtly permeated mainstream culture.

Credit: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

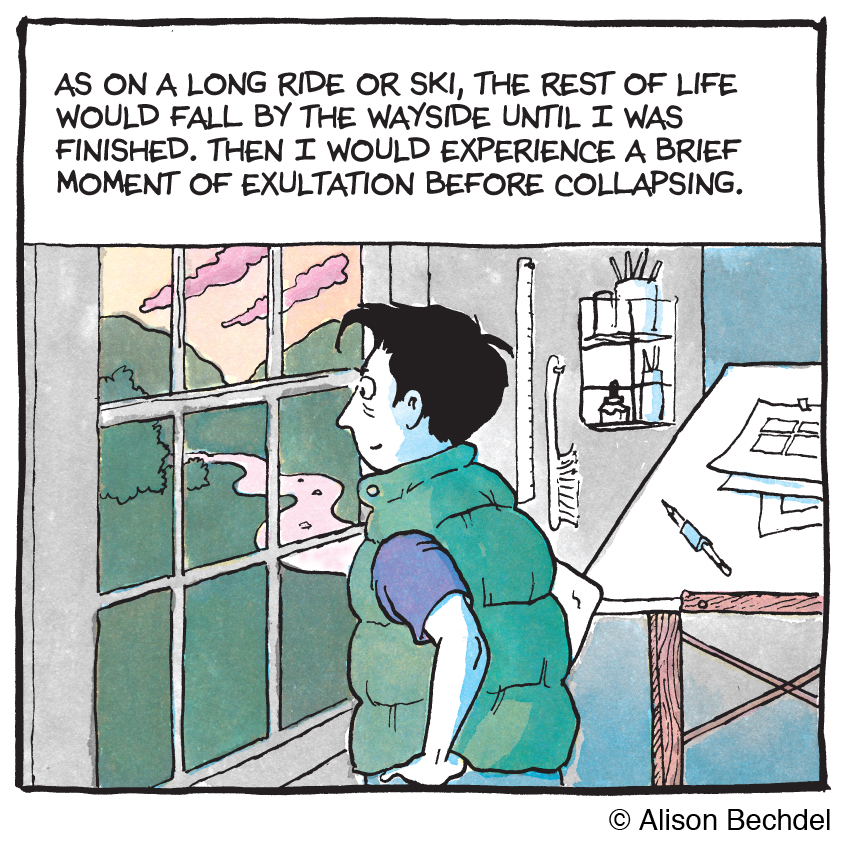

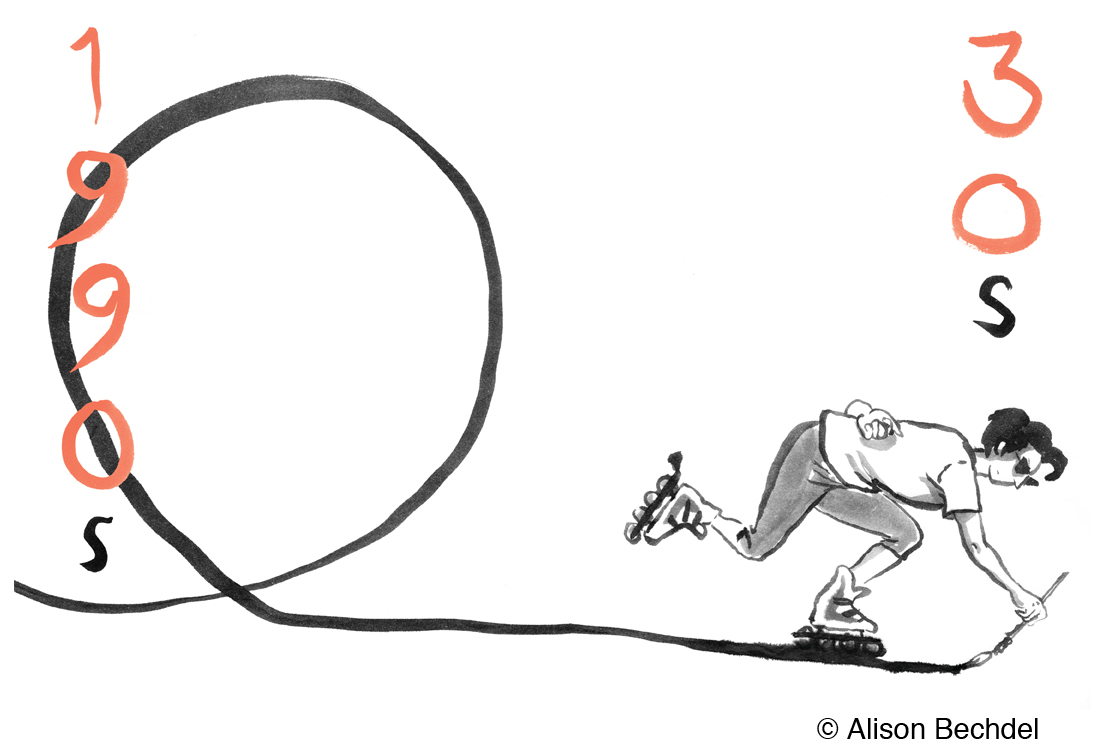

In her new book, The Secret to Superhuman Strength, Bechdel examines her lifelong pursuit for strength, health and self-sufficiency through skiing, running, karate, biking, yoga, inline skating, mountain climbing and other exertions. The comic’s chapters are divided into decades and recount how she pursued and used exercise at different stages of her life. Woven into her personal story are musings about writers who also sought transcendence through activity in nature, including Margaret Fuller, Samuel Coleridge, William Wordsworth, Jack Kerouac and Adrienne Rich. She explores her quest to quiet her mind through activity, to achieve what is sometimes called “flow.”

Credit: Alison Bechdel

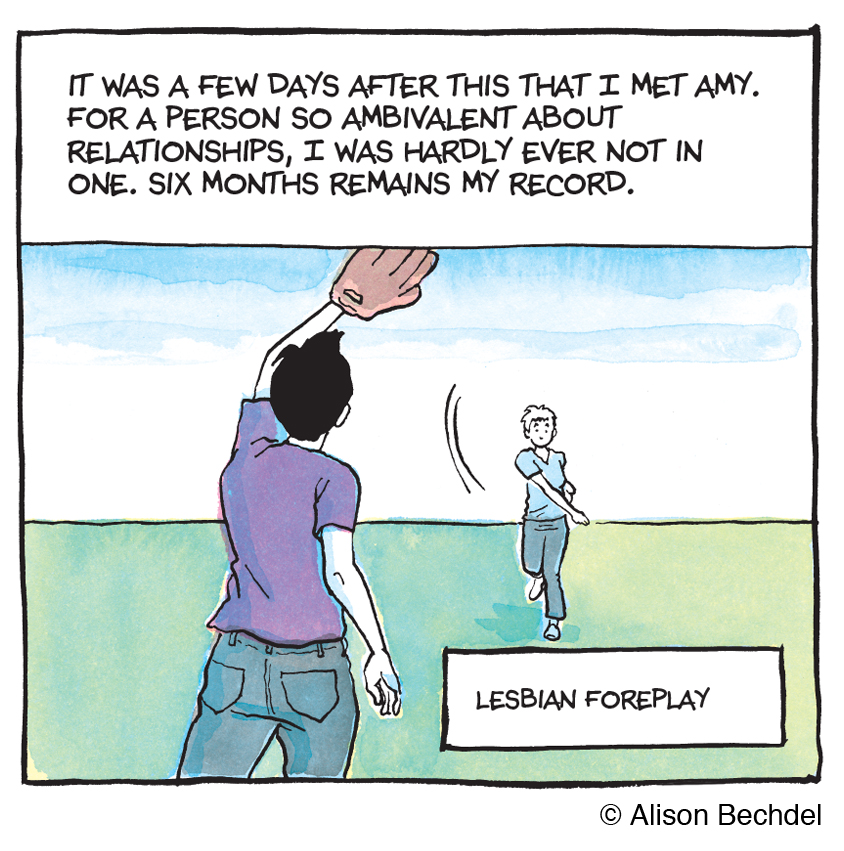

Her portrayals of women’s physical pursuits highlight a time-honoured aspect of dyke culture. When she joined a women’s karate class, Bechdel writes, “Both my cartoons and my karate practice were part of some larger project. The strange new word ‘community’ entered my vocabulary.” Queer women need strength and independence to survive. Exercise and sports foster connections, from softball teams to lesbian camping trips—and the sensuality of bodies in motion can’t be denied.

Credit: Alison Bechdel

At one time, Bechdel considered making a memoir about her relationships, but that concept instead evolved into the graphic memoir about her mother, a lover of culture and amateur actor who was in a difficult marriage with a closeted gay man. But in The Secret to Superhuman Strength she does examine how her relationships are affected by her obsessions, and how comics are her “other girlfriend.” She tends towards serial monogamy and describes how she and her different partners negotiate her workaholic habits, as well as her romantic crushes, couples counselling, arguments about where to live and how often to take vacations. When she meets her current partner Holly, who is polyamorous, she writes, “I wasn’t interested in multiple girlfriends, but what if it could be okay to admit that my primary commitment was to my work?”

The Secret to Superhuman Strength is beautiful, endearing, layered, funny and complex, and Bechdel’s art perfectly depicts her compulsive thinking about compulsive thinking. Because queer women find so few accurate examples of themselves in the arts and media, Bechdel’s work has been especially welcomed and loved. She mirrors a world of women who live within an LGBTQ2S+ community, are politically aware, androgynous and active.

Credit: Elena Seibert

I’ve known Alison for decades. We met in the 1980s when there were few openly queer cartoonists creating LGBTQ2S+ content. Most of us knew each other, and we shared techniques and career advice. I remember an evening in my New York apartment, watching the late Howard Cruse (Gay Comix’s founding editor) painstakingly demonstrate to Alison his exquisite method for cross hatching and stippling. Often I’d meet Alison at book talks or panel discussions, and afterwards our queer cartoonist gang would gather in a restaurant or bar, talking excitedly about pens, pay rates and publishing gossip. But while some of us partied in excess, Alison was always more industrious, famously hating to take vacations and most happy when at work. As her audience and reputation deservedly grew over the years, she has continued to be exceptionally generous and helpful to other cartoonists.

We recently discussed her new memoir. As a cartoonist and graphic artist myself, I was particularly interested in learning about her new cartooning techniques and artistic decisions.

How does your physical exercise inform and nurture creating comics?

Making comics is a physical, embodied activity in a way that writing isn’t. I’m dealing with not just the ink and the pen and the paper, but with finding a comfortable working position so that I can draw for extended periods without injuring myself. On deadline, drawing can be a bit of an endurance event. Regular exercise really helps with all of that. Maybe it’s sort of like being an actor—my body is to some extent my “instrument.”

“I was often the only woman in the weight room, but I felt like I really understood the guys there. They wanted to be more ‘manly,’ that is, bigger and stronger, just like I did.”

Why were you fascinated by Charles Atlas and Jack LaLanne when you were young? Interestingly, both are images of hyper-masculinity but can also be seen as very homoerotic.

Yes, there’s something very queer about those Charles Atlas ads, and sort of double queer that a little girl found them so compelling. I haven’t really analyzed this very deeply, but now that I think of it, the ads were selling a performative masculinity that one could learn. They were saying men need to do something to be proper men. Later, as an adult, I was often the only woman in the weight room, but I felt like I really understood the guys there—they wanted to be more “manly,” that is, bigger and stronger, just like I did.

After doing research for this book, did you write out a complete script before drawing it? And did the text change as you created the art?

I mapped the book out pretty thoroughly before I started doing the actual drawings. I compose in a drawing program, in Adobe Illustrator, so as I write I’m laying out panels and envisioning what the images will be, but I don’t bother to actually do much drawing until the writing is figured out because I’d just end up having to change it.

I love that this book is a larger size than your previous books.

That was my choice. I just wanted to work bigger, to not be so constrained. I finally got a large-format scanner, which enabled me to increase the dimensions of my page size a bit. Fortunately, my publisher was game.

This is your first full-colour book, with colour done by your wife Holly Rae Taylor.

I had come up with a colouring technique that I thought would be simpler and quicker than doing full colour—I’d do layers of cyan, magenta and yellow and just colour some elements to each panel, but not everything. There would be some areas of overlap with secondary colours. But then I was running out of time, and could see that even with this simplified scheme I was not going to have time to colour the book myself. I was really lucky that Holly was able and willing to

take it on. But once she got started, that abstract colouring plan went out the window and we went for more conventional colour. And I had to let go of a lot of control. I would give her a colour sketch for each page, but in the end she made a lot of the decisions herself.

And didn’t you use an elaborate and laborious colouring process?

Yeah. We didn’t want to be working on the computer, so all the colour was done with an actual brush on paper. And Hol’s cyan, magenta and yellow layers were actually painted with several different intensities of gray ink wash. It’s very complicated to explain, and even more complicated to do. My quick-and-easy plan turned out to be a lot more work than just doing it all in Photoshop.

How did you like collaborating with another person?

It took a little getting used to, but once we got in a groove, I really liked it. It was fun to have Holly there in the trenches with me, instead of being all alone.

Credit: Alison Bechdel

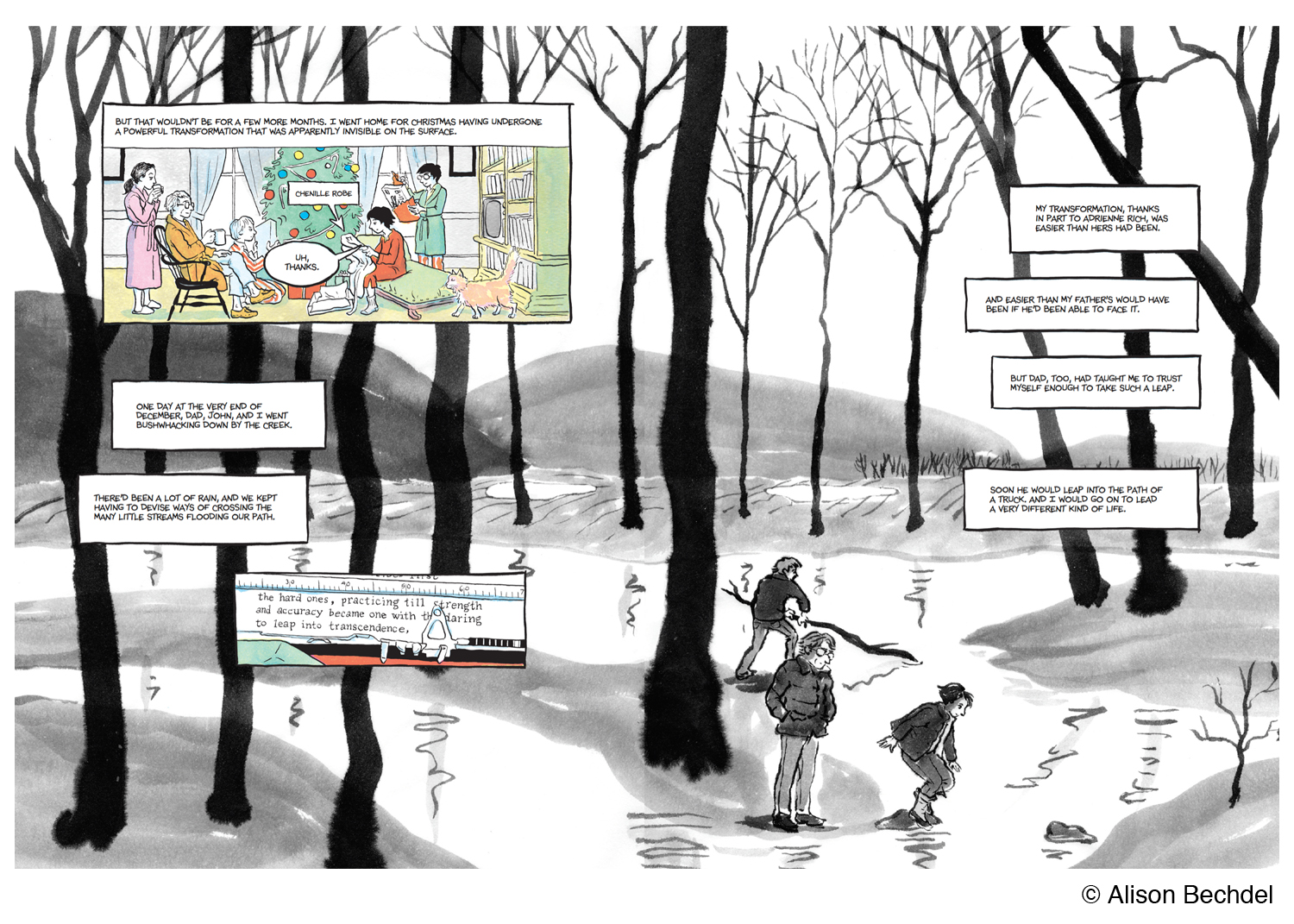

You include black and white sumi-e-style brush drawings [a style of Japanese ink painting] to introduce each chapter and as double-page spreads to depict epiphanies. Why did you choose that?

I pushed myself to let go of my comforting, precise ink lines at certain points of the story. The sumi-e scenes are meant to evoke a different register of reality than the everyday one we spend most of our time and awareness in, a register where things start to blur together. I have much less control with the sumi-e brush, and the technique has to be done much more spontaneously than my regular drawings, which go through many layers of preparatory sketches before I ink them. It was an attempt to jump start the kind of flow I felt as a little kid when I drew completely spontaneously.

Your page layouts are spectacular and complex, with many full-page bleeds and overlapping layers of content. What is one of your favourite pages?

I’m actually not great at thinking in terms of page spreads, but I pushed myself to do better at that in this book. The bleeds were surprisingly complicated to figure out, but I love the sense they give of the book spilling off the page and out into the world. I’m fond of this spread at the end of chapter two, where you can see the regular “everyday” world in the overlaid panels, with the more numinous sumi-e world behind it.

Credit: Alison Bechdel

Skin colours are depicted as the colour of the white paper with blue shadows. Why did you make that choice?

Laziness, mainly. Skin tones would have just been a ton more work. Plus, with our crazy colour separation technique, it would have been a bit of a crapshoot how they turned out, and weird skin colour is worse than no skin colour. But I also like the way every square inch of every panel is not filled in, that there’s some bare paper showing. The blue shadows are actually everywhere—that’s the one element of the colour that I contributed, doing a shading layer for each page.

Do you now think of your present actions and daily life in terms of how they will appear in future comics?

I try not to! A writer friend of mine calls that “strip mining.” I love that analogy—it really would be sort of destroying your own lived experience if one did it just in order to write about it.

I know you love being alone, in your head, buried in your work or doing something physical in nature. Was being locked down during the pandemic a relief for you?

Yes! It was actually pretty awesome.

Alison Bechdel and Jennifer Camper are two of the five artist featured in the new documentary No Straight Lines: The Rise of Queer Comics. Along with the filmmakers and fellow comic book artist Rupert Kinnard, the two take part in an after-film conversation moderated by Sasha Velour for the film’s premiere at the Tribeca Film on Saturday, June 12.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra