New York writer Sarah Schulman’s new book Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993 is the culmination of one of the biggest projects of an already impressive writing career. But the 736-page work certainly won’t be the end of Schulman’s intense connection with one of the most audacious and inventive social movements contemporary America has ever seen.

At its peak, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) New York had as many as 800 people attending its rambunctious weekly meetings, while thousands attended its larger protests. “A few committed activists, when focused on being effective, can accomplish a lot,” Schulman writes.

In an interview, Schulman tells Xtra that the book, out this week, is intended not only as a chronicle of the movement, but as a correction to other representations of early AIDS activism and as an inspiration to contemporary activists who might be able to borrow a trick or two.

Back then, it was impossible to imagine the antiretrovirals that would, starting in the late 1990s, turn HIV/AIDS into a manageable and noncontagious illness for those who have access to medication. But the economics of that access, where lower income people in North America and around the world can’t afford the drugs, suggests there is still unfinished business in ACT UP’s vision.

“The fact that we were able to beat HIV but we couldn’t beat capitalism is something that was not predictable at the time,” Schulman says. “The idea that the more progress we made in treatment, the more the differential of access that exists in the United States would become emphasized, that was also unclear.”

Founded in New York in March 1987, ACT UP was a desperate response to the early AIDS crisis, when people were dying horrible deaths, effective treatment seemed like a pipe dream and people with AIDS were treated as pariahs who were perhaps deserving of their fatal diagnosis. Schulman, who had been writing about the AIDS crisis since 1982 for queer and feminist media like Gay Community News and The New York Native, joined the organization just a few months after it was founded.

Credit: Drew Stevens

The first protest Schulman attended was in July 1987 against Memorial Sloan Kettering, a research institution in New York which had left marginalized people out of its experimental drug trial. “They did an around-the-clock picket, and people showed up for it, and they maintained the silence so as to not disturb the patients. I thought, ‘Well, this is great. It shows commitment and care and it’s very imaginative,’” Schulman says.

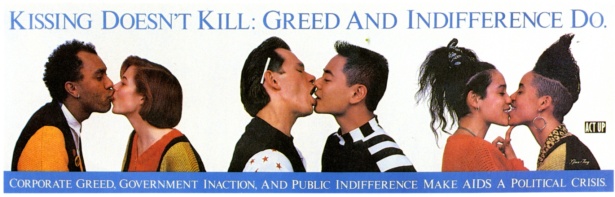

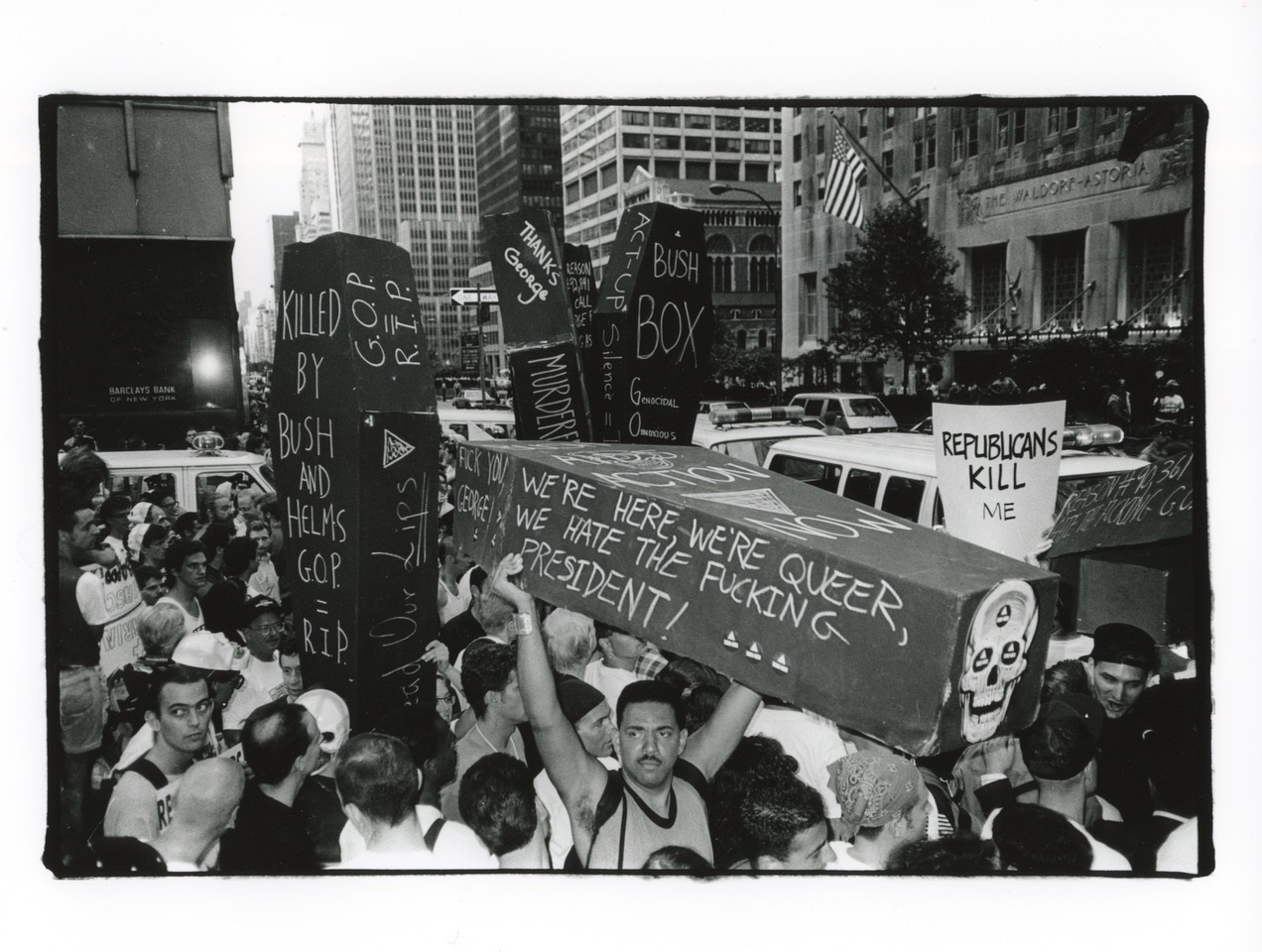

The group’s direct actions—against government, drug companies and other institutions that didn’t take the AIDS crisis seriously enough—were often driven by white-hot anger, yet were executed with acumen and flamboyance. Their use of art and media was a big part of their power. The poster of “Silence=Death” over a pink triangle has become iconic. They threw fake blood at the computers of officials, even as they managed to get meetings with power brokers.

ACT UP popularized the “die-in,” a version of a sit-in where protesters laid like corpses on the ground, a tactic that’s since been employed by movements ranging from cycling safety to climate change to Black Lives Matter. At their legendary and controversial Stop the Church action on Dec. 10, 1989, ACT UP interrupted mass at New York’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral, resulting in the arrest of 111 protesters and prompting then-U.S. president George H.W. Bush to call the group “outrageous.”

Their direct actions, their media savvy and, most importantly, their results, inspired the formation of 148 chapters around the world. Among the accomplishments ACT UP can take credit for were changing the procedures used by the United States’ Food and Drug Administration (FDA) when releasing of experimental drugs, demanding large-scale condom and clean needle distribution programs, changing the definition of AIDS to include infections common to women, getting pharmaceutical companies to lower drug prices and bringing AIDS and safe sex awareness to the mainstream.

Credit: Courtesy Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Yet ACT UP New York did its revolutionary work in the era before the internet took off big. Schulman, who had already written a memoir about the AIDS crisis, The Gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Imagination, worried that the work of what she calls the “most successful recent social movement in America” was becoming invisible, despite her belief that ACT UP’s legacy could be especially useful for contemporary social movements.

And so Let the Record Show is not a traditional history of an organization. It’s not structured chronologically, but through profiles of people and an analysis of how their backgrounds, skills and goals drove the group forward or, in some cases, sabotaged it.

Schulman has arranged all of these testimonies with an eye for being helpful to activists in the here and now. For example, this bit could be taken as PR 101 for how to work inside the tent and outside the tent at the same time: Though ACT UP demonstrations could be a motley crew of “people in T-shirts or bomber jackets… lying in the middle of the street yelling, pumping their fists in the air,” she interviewed one member, Jay Blotcher, about how he approached the media during these events. He dressed in a suit and tie. “That was a really contrived, but focused way of trying to insert a little legitimacy in there,” Blotcher tells Schulman. “And, they would be soothed by the fact that a person with a seemingly sane face was disseminating the information.”

Credit: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Blotcher is just one of about 140 people who are described, quoted and, ultimately, assessed, in Let the Record Show. “I’m very fair,” Schulman says. “The people who I don’t like at all—and I think it will be hard for you to know who they are by reading the book—I give a lot of space. I just decide to let people describe themselves and to go with it.”

The book is occasionally funny, but only darkly and ironically so. For example, Schulman describes how ACT UP was “awkwardly shoved into the gay male historical trajectory” because the media covering them was predominantly white and male, who liked narratives of “the young, robust, white male body… reduced to rubble, allowing the straight viewer to feel sorry while simultaneously being comforted by the weakness and punishment of the queer.” On stage at a writers’ event in Boston in the early 1990s, Schulman brought the issue up with Larry Kramer. The playwright, author and gay rights activist had helped found ACT UP and was perhaps the best-known person associated with it. “I suggested, in front of an audience, that the next time Larry was called by the media, he could refer them to a person of colour or woman in ACT UP. And Larry responded, ‘But Sarah, shouldn’t we use our best people?’”

Then there are lesser known figures like Karin Timour, a straight woman who worked as a bookkeeper and thought ACT UP might be a “great place to make some friends.” At one meeting she volunteered to work on insurance and ended up “masterminding an enormous campaign conducted by snail mail in 50 states that led to winning basic insurance eligibility for people with AIDS. Over 600,000 HIV-positive Americans became eligible for insurance because of her work,” Schulman writes. But Timour had not been interviewed before Schulman did so.

The 140 people written about in the book are not the only resources Schulman had access to for research. Though the book is long, it synthesizes an even more massive database: The ACT UP Oral History Project, which contains 187 interviews with people in the movement, which Schulman and filmmaker Jim Hubbard conducted over the course of 18 years.

Schulman had hoped other creators would use the interviews to create work about ACT UP, but found that few were interested. She was frustrated with the other things that were being said and written. “These things started to come out that really misrepresented to a degree that was very disturbing and also divisive and it became kind of a state of emergency,” she says. “The previous history [David France’s 2016 book How to Survive a Plague: The Inside Story of How Citizens and Science Tamed AIDS] did something very divisive to the movement, which is that it focused on heroic individuals. And that’s not how change gets made in America. Changes are made by coalition. So it created a distortion of the reality.”

Credit: Courtesy Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Schulman says that works like France’s book, which was made into a documentary in 2012—or even Tony Kushner’s two-part play Angels in America, which was made into an HBO series in 2003—are “very well positioned and highly rewarded works that may have some value emotionally. But historically, they’re actually inaccurate. And it’s time for them to stop being the reference points.”

Angels in America, for example, ends on a note of hope with the arrival of the drug AZT when, as we know in retrospect, AZT didn’t work well at all. Other versions of the ACT UP story present a heroic view of white gay activists, rendering invisible the women and people of colour who may not have had the connections to get meetings with the white men who ran things, but whose creativity, determination and experience in other social movements made ACT UP so effective.

For example, the idea of patient-centred politics—the declaration that people with HIV/AIDS are the experts, not the doctors and scientists and drug companies—was imported to ACT UP from the feminist health movement by activists like Marion Banzhaf, “who nobody’s ever heard of,” says Schulman. The group fought against placebo trials on infants because they conflicted with notions of patient consent—babies can’t agree to be guinea pigs—that also came from feminist thinkers.

Schulman concludes that social change is achieved by a small group of people working hard, not large groups of people doing light lifting. “It takes a very focused and committed group that’s determined to be effective,” she says. “There’s a lot of people who waste their time being in political movements sort of halfway, who are not effective. I think there are people who just want to feel good more than they want to actually win. And that can be an obstacle.”

Unfortunately, so much of the focus and commitment that made ACT UP so effective—and the passion that made participants feel like they were part of a supportive community—was driven by desperation; if they didn’t advocate for themselves, nobody else was going to step in. “People with AIDS had immediate needs that were very concrete and they knew what they were,” she says. “So ACT UP would take the responsibility to design the solution in a way that was reasonable and then presented fait accompli to the powers that be. There’s a very mature attitude in there because we’re not treating the power as this parent who is supposed to solve the problem. We take the responsibility to come up with the solution.”

“We’re not treating the power as this parent who is supposed to solve the problem. We take the responsibility to come up with the solution.”

Being pre-internet and pre-social media also forced ACT UP members to get together in rooms to share ideas and information. People without any post-secondary education taught themselves to read scientific studies and would summarize them out loud for others. In-person human contact nurtured personal connections (as well as romantic and sexual relationships) that increased their feeling they could change the world. “People spent a lot of time together as a people, lived together, worked together. They were in ACT UP full-time.”

Credit: Courtesy of Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Despite these synergies, ACT UP New York’s internal politics were hardly harmonious. When I ask Schulman about ACT UP’s failures, she points to the moment in 1992 when several members of the Treatment and Data Committee split to form the Treatment Action Group (TAG), which was the beginning of the end of ACT UP’s most productive period (though the New York organization still exists). “I detail the split very precisely so that everyone can follow it and understand exactly what happened. But in truth, I think that we just kind of all went a little crazy because it was so difficult.”

I suggest to Schulman that most movements forged out of passion and specific circumstances eventually wear themselves out, fall apart or mutate into something else, so a split shouldn’t be considered a failure. So Schulman gives me a more obvious example.

“There had been a lot of distrust, but I never understood what it was about.”

“When I interviewed [ACT UP member and now executive editor of GEN by Medium] Garance Franke-Ruta as an adult, she said that she had come to understand later that speeding up the drug availability process [one of ACT UP’s biggest demands at the time] actually did benefit pharmaceutical companies and created problems [in the drug approval process] that exist today. We were naive to that,” she says.

Toxic behaviours also bubbled underneath heroic images. “There was this kind of puppet master thing that went on at ACT UP that was very destructive, where older men would find younger men who everyone liked and get them to front certain proposals. I only learned about it by doing the interviews. There had been a lot of distrust, but I never understood what it was about. I think people thought something was being withheld.”

Another sore point: In 1990, women in ACT UP were trying to get the definition of AIDS changed; the disease had been defined by the infections of the men first diagnosed with it, but women often had different symptoms and so were frequently misdiagnosed, making them ineligible for treatment and other programs. This working group held a conference in Washington that the head of ACT UP’s Treatment and Data Committee, Mark Harrington, did not attend, despite being a desired guest. While the conference was happening, Harrington was spotted at the hotel bar where the conference was being held, on his way to a dinner party with Anthony Fauci—yes, that Anthony Fauci, present-day chief medical advisor to the president of the United States. At the time, Fauci was the leading researcher into the treatment of AIDS and was very influential.

The women felt betrayed and suspected Harrington failed to bring up their issue with Fauci. There were hard feelings all around. In the book, Harrington tells Schulman that his Fauci meeting revealed “a lack of coordination if not outright distrust between these groups. And I’m sure that contributed to some of the mistrust and antagonism that was taking place.”

Though Schulman has now created an indisputably authoritative record of ACT UP New York and the people who drove its success, she is still not yet done with the story: The rights of the book have been sold for the purpose of turning it into a TV series.

“I think it would be a three- to five-year dramatic series,” she says.

I ask her if all this makes her feel nostalgic. She doesn’t hesitate when she answers, “I’ve never stopped thinking about AIDS activism, so there was no flashback element. As they say, AIDS is not over.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra