UPDATE: On June 11, the Federal Court ruled that they would allow the challenge against Health Canada’s role in Canadian Blood Services (CBS)’s policy on a deferral period for blood donations by men who have sex with men (MSM) could proceed to the Human Rights Tribunal.

“The decision affirms that it is appropriate to examine Health Canada’s role in upholding the blood ban, contrary to the federal government’s statements,” says Shakir Rahim, an associate at Kastner Lam LLP in Toronto, and Christopher Karas’ lawyer in the matter. “It is regrettable that Mr. Karas was forced to fight a costly and difficult legal battle just to continue his human rights complaint.”

In his ruling, Justice Richard Southcott noted that the Human Rights Commission’s assessment report stated that there appears to be a “live contest” as to the exact nature of the relationship between Health Canada and CBS, which warrants further inquiry. He also noted, however, that the Commission has broad discretion as part of its screening function before recommending cases to the Tribunal.

“The Commission need not determine that the complaint passes some merit threshold before referring it to the Tribunal,” Southcott wrote. “It must simply be satisfied, having regard to all the circumstances of the Complaint, that an inquiry is warranted.”

Justice Southcott also granted Karas’ costs in the matter, as he was successful in his application before the court.

Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government is asking a federal court to quash a human rights complaint challenging Canadian Blood Service’s (CBS) ban on blood donations from men who have sex with men (MSM), despite election promises to the contrary.

Government lawyers are arguing that Health Canada doesn’t play a meaningful role in determining the CBS’ policies, including on the deferral period for MSM. The Tribunal’s examination into CBS will carry on regardless of the outcome of this trial.

“CBS operates at arm’s length from Health Canada, and so the [Canadian Human Rights] Commission made an error in deciding to refer this complaint against Health Canada to the Tribunal,” the government’s factum states. “If the complaint were to be found valid, there is no remedy that the Tribunal can order against Health Canada that could vindicate Mr. Karas’s [the complainant’s] rights.”

Christopher Karas, who filed the human rights complaint against CBS and Health Canada in 2015, says that he sprung to action after he was denied the ability to donate blood due to his sexual orientation, and citing in his filing that he felt he was “of very little value or that he could not make any significant difference in someone’s life.”

Currently, men who have sex with men and some trans women in Canada are barred from donating blood if they do not remain abstinent for a period of three months. Trudeau’s Liberals made ending the blood donation ban an election promise in both 2015 and 2019.

“It was clear to me then that I had to challenge the policy, and I had previously had a complaint at the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario against my school board, so I was familiar with human rights bodies, and wanted to use the same venue at the federal level,” Karas said in an interview with Xtra.

“We took it upon ourselves to challenge the policy at the Canadian Human Rights Commission, which acts at the gateway to the Tribunal, and we went through that process with the investigation and the assessment and conciliation, and proceeded to a decision that referred the matter to the Tribunal,” says Karas. “At that point, the Attorney General of Canada sought an application for judicial review on that decision.”

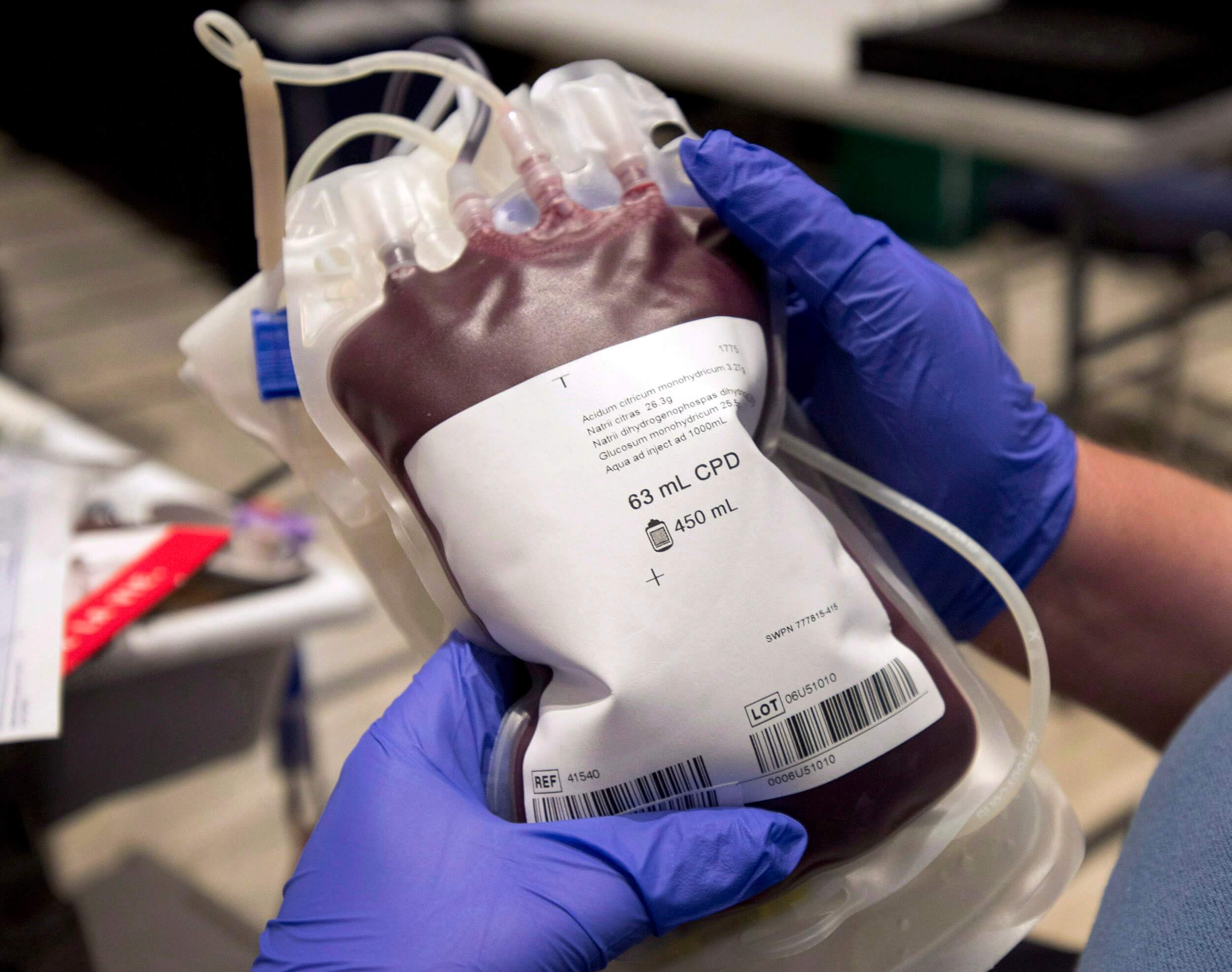

Credit: Hamzah Amin

According to court documents, Karas sought $20,000 for pain and suffering and $20,000 in damages as a result of the oppressive policy. He also sought to have the blood deferral policy overturned, an apology issued by Health Canada and CBS’ arms-length operations be forfeited because of their lack of accountability.

Documents also showed that a conciliation process had taken place where, in 2019, Health Canada offered Karas a $5,000 settlement to compensate him for his legal fees and to assure him that he was not alone in his fight, which Karas declined.

Shakir Rahim, an associate at Kastner Lam LLP in Toronto and Karas’ lawyer in the matter, says that if Health Canada were removed from the complaint before the Tribunal, it would remove the accountability of the current government from the process.

“Health Canada does play a role in the screening criteria used by CBS,” Rahim says. “They have made the decision to fund the research around the screening criteria for MSM donors, they have pre-submission meetings with the CBS in which they can provide feedback to CBS on donor screening criteria and regulatory requirements. They are the ultimate body that does have to approve the screening criteria in question.”

A spokesperson for Minister of Health Patty Hajdu says the minister is unable to comment on the case because it is before the courts.

Rahim says that Hajdu has spoken about the government’s desire to end the MSM blood deferral policy. He also says that the Commission found that Health Canada and CBS do have a relationship that the Tribunal should examine.

“The government is trying to shut down the consideration of the very real issue of Health Canada’s responsibility to rights obligations as it relates to this policy,” Rahim says.

University of Ottawa law professor Y.Y. Chen says that the federal government’s case is strong with this particular challenge, both because of the nature of Health Canada’s relationship with CBS and the powers it has over the regulation of blood products.

“There is case law that says that CBS really is at arm’s length from the government,” says Chen.

“The government is trying to shut down the consideration of the very real issue of Health Canada’s responsibility.”

There have been other challenges to CBS’ previous MSM blood donation ban, before a deferral period was put in place. Most notably in the Ontario Superior Court in 2010, the court ruled that blood donation did not constitute a “service,” and that the policy was justified given the health risks involved.

A 2017 Federal Court decision also ruled that Health Canada did not have a role to play in CBS’ screening policies in a case involving a young woman who didn’t have the mental capacity to understand the donor forms when she tried to donate blood.

“What the government does is simply say whether or not CBS’ policies meet some kinds of basic standards, and what the claimant wants in this case is to go beyond that minimal standard, to say that in addition to thinking about safety, we also need to think about human rights implications,” Chen says. “That is not part of the Food and Drugs Act regulations, which is where the power of Health Canada to regulate CBS is based.”

Rahim says that neither of these previous cases should be binding on whether the Tribunal should be able to review the relationship that Health Canada plays in the matter.

“We’re seeing a federal government that is intervening more often than it normally would in preventing human rights cases from proceeding,” Karas says. He cites the challenge of the Tribunal orders of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society—though in that case, the federal government is arguing that the Tribunal exceeded its statutory mandate in granting individual remedies for systemic discrimination.

“It’s time for human rights activists to call on the government to stop this type of incendiary halting or delaying of proceedings for their own personal interest,” Karas says.

Karas believes that the minister of health has the authority to make the changes to CBS’ policy but is unwilling to do so “because they are afraid it will be seen as inappropriately intervening in the blood donation system.” That, he says, could be rooted in fears around the 1980s tainted blood incident, which led to thousands of Canadians becoming infected with hepatitis C and HIV.

The Krever Report, stemming from Canada’s tainted blood scandal, specifically recommended that the Health Protection Branch of Health Canada “must at all times act at arm’s length from the organizations it regulates,” having found that the governance structure of the previous Canadian Red Cross’ blood donation activities was blurred and ineffective.

“It is fairly exceptional for the federal government to intervene at this stage.”

Chen notes that CBS’ structure may look like it’s closely linked to the government, as all members of its corporation are the provincial and territorial health ministers across the country, but they elect a board of directors that controls the day-to-day operations of the organization. Most of CBS’ funding comes from provincial and territorial governments.

“These health ministers exert only limited control over the direction of CBS’ policies,” says Chen.

Chen adds that because CBS is separate from the government, it’s harder to apply the Charter of Rights and Freedoms to its actions.

Rahim says there should be an evaluation of whether Health Canada is in violation of its human rights obligations to the queer community.

“It prevents the critical evaluation of what they have done, whether they have acted speedily enough or whether they have lived up to the promises they’ve made,” Rahim says. “It is fairly exceptional for the federal government to intervene at this stage.”

The government is also seeking to recoup costs from Karas as part of their challenge.

Chen adds that while the government’s case is strong, denying the Tribunal the opportunity to conduct an examination—as opposed to letting the process play out and responding to the finding—doesn’t make sense.

“This is an access to justice argument,” says Chen. “Why deny the claimant a chance to access this particular mechanism?”

The hearing at the Federal Court will be held on May 27.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra