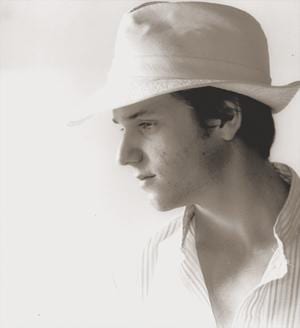

Chris Bearchell (left) at the TBP victory celebration, 1979. Credit: (courtesy of CLGA)

The Body Politic office in May 1976, at 24 Duncan St. Credit: (Gerald Hannon)

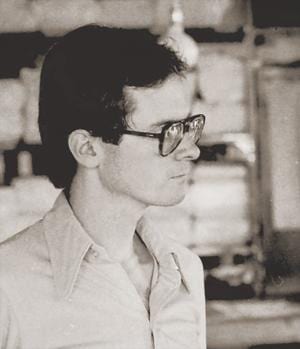

Robin Metcalfe, a regular contributor to TBP, 1976. Credit: (courtesy of CLGA)

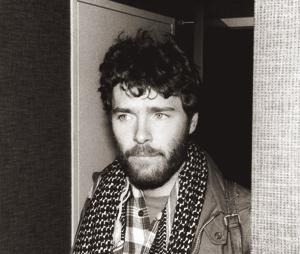

Tim McCaskell at a press conference following the first acquittal of TBP in 1979. Credit: (courtesy of CLGA)

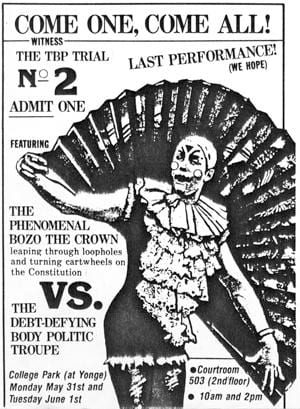

In 1982 the collective was charged with obscenity for the second time. Credit: Xtra files

Rick Bébout, who passed away in 2009, tirelessly contributed his prolific design and writing skills to TBP. Credit: Xtra files

In 1987, when The Body Politic folded, a gap opened up between the generation of gay liberationists and young queers who would come of age in the decades to follow.

The moment marked the end of a media venture that shaped the scope of gay and lesbian politics in Canada and beyond. The Body Politic, published by what would become Pink Triangle Press, came to serve as a paper of record in documenting activism, arts and culture, as well as the changing realities and challenges faced by lesbians and gays. The paper brought together a network of sex radicals who documented, celebrated and critiqued the arrival of the new world of gay life in urban centres throughout much of North America and Europe. When The Body Politic disbanded, the politics of sexual liberation that guided the work of the paper continued in different forms, through the work of Xtra and wherever people from The Body Politic ended up, but the social world of the paper ceased to exist. My doctoral research in anthropology at York University has allowed me to explore that social world. Conversations with people who were involved with the paper during its 15-year run (1971–1987) have helped to shed light on the significance of The Body Politic to queer history and the value of the paper as a social and intellectual experiment. Beyond simply celebrating the paper, it is worth thinking about how and why it is still relevant today and what we might learn from those who devoted so much of their time and energy to the work of sexual liberation.

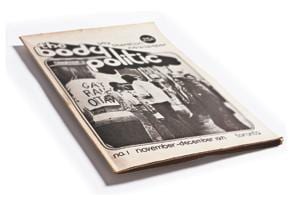

The origins of The Body Politic have been well documented by Peter Zorzi and Charles Dobie, both of whom were involved with the first issue. In the autumn of 1971, members of radical activist group Toronto Gay Action got together to spread the word about the first gay demonstrations in Canada, held the previous summer on Parliament Hill in Ottawa and in Robson Square in Vancouver. By creating a newspaper, the message of coming out of the closet could reach a broad audience and help to recruit new members to the growing gay liberation movement. The aims and goals elaborated in We Demand, a piece written for the first demonstrations and later printed in the first issue of the paper, outlined a set of tangible concerns dealing with policing and law protections, but the paper’s liberationist aims were much broader in scope. The newly formed collective sought to radicalize gays and lesbians and to challenge the conspiracy of silence about homosexual desire.

The paper is often remembered for its sometimes-controversial treatment of hot topics. The publication of articles like “Of Men and Little Boys” and “Men Loving Boys Loving Men” attracted attention from various opponents who accused the paper of promoting pedophilia. The second article and another on the subject of fisting raised the eyebrows of many readers and attracted attention from authorities who brought charges of obscenity against the paper. Accusations of racism were brought forward when the paper published a classified ad from a man looking for a black houseboy. These controversies are easy to recall, as they mark moments when the paper made headlines in other newspapers across the country. But the actual work of The Body Politic through the ’70s and ’80s was often more subtle and worked through very careful analysis of sexuality and the lived experiences of gays and lesbians.

***

The collective

As many Body Politic people described the space, it was one of intense debate and vibrant social life. Weekly meetings of the collective were lively and engaging and often quite epic. Group decisions were made by consensus, whereby members who disagreed on an issue or theoretical approach went head-to-head in an effort to grasp a middle ground and to talk their way to some kind of agreement. Whether individuals were on the collective, making decisions about which articles to run, or were carrying out more mundane tasks like answering telephone calls or sorting classifieds, the time commitment to the paper made for ongoing face-to-face interaction with others. For those on the editorial collective, the circulation of memos and the constant flow of materials created a web of constant activity. Discussions about recent articles, comments on news and current events and theoretical debates about sexuality circulated within the office, weaving together a community of activists and writers. Long before the days of desktop-publishing software, the task of producing a newspaper involved the labour-intensive work of editing articles, doing paste-up and revising the final proof before it went to print. It meant that people spent long hours working side by side with one another.

Long-time volunteer Gerry Oxford remembers his own experience with the paper with fondness. He recalls, “It was such a gift if you were a smart kid coming out. You know, it was unlike anywhere else in the world. It was a place where all these really smart people were doing really interesting things and having fabulous discussions.” The excitement of being surrounded by others who were so passionate about ideas, politics and the possibility of changing the world fuelled the paper. When an issue went to press, a debriefing session known as a “postpartum” would be held a week or so later at the home of a collective member or at one of the collectively run households where key Body Politic figures — like Ed Jackson, Merv Walker and Paul MacDonald — lived. These gatherings were an occasion for people to discuss their reactions to articles and, sometimes, to share grievances about how articles appeared in the final version of an issue. It was in working through ideas and political views and in continually educating one another that the productive engagement of liberation was sustained.

East Coast correspondent and collective member Robin Metcalfe describes his work with the paper as a formative experience that provided an education in political theory, as well as writing. He explains, “I can’t stress too much the importance of The Body Politic for me both in terms of giving me a theoretical framework and a practical experience with writing. I consider it my first sort of professional venue — although I never got paid.”

While there were paid staff members, no one ever received payment for his or her writing, which meant that the paper relied heavily on volunteer labour. The culture of giving that enabled the work of the paper has been detailed by the late Rick Bébout. On his website Bébout explained the significance of gift-giving to the spirit of the paper, where no one ever calculated the cost of their efforts and the few staff members who did receive a paycheque also volunteered their time. As he described it, the paper was a labour of love for those willing to dedicate their time and energy to it. In this sense, these efforts were part of a gift culture. In Bébout’s view, “Gifts move in circles: they come back to the giver as part of that circle. And they come back transformed, enriched as they were passed along.” This is how the paper grew to be a publication of international renown — through the concerted efforts of a small group of individuals who were willing to work together to change the world.

***

Defining the path

Critical analysis informed so much of the discussions, writing and organization of the paper. Many of the key thinkers had university degrees, but this was by no means an indicator of one’s skill as a writer or critical thinker. The Body Politic collective were smart people who brought to the paper their talents as writers, editors and theorists. But they all learned from one another, sharing their expertise. What mattered was their willingness to examine tough questions about sex and society and to put what skills they had to good use.

As a paper with a strong emphasis on social critique, it garnered a reputation as a difficult read. Articles were often long, sometimes serialized over more than one issue. News and event listings were written in plain English, but analytical articles were often pitched to a reader with a larger-than-average vocabulary who was familiar with intricate political argumentation. This tendency toward theory was not mere intellectualism on the part of writers but sought to challenge common-sense ideas about sexuality, culture and history. It was in the pages of The Body Politic in 1974 that the world first read James Steakley’s research on the Nazi persecution of homosexuals during the Holocaust. In 1982 the paper printed anthropologist Gayle Rubin’s path-breaking work on sadomasochism, critiquing anti-sex feminist politics of the day. The late Michael Lynch and others wrote levelheaded and insightful commentaries on responses to HIV/AIDS and the growing epidemic. In many ways, the paper served as a journal for what would become the now well-established field of sexuality studies.

Collective member Gillian Rodgerson remembers theoretical debates of the early 1980s as a mingling of perspectives. She says, “People like Sue Golding were writing about Michel Foucault’s ideas. There were people who were doing what we would now call queer theory, and others were coming at it from having worked with the traditional left… All these different schools of thought.” At times, this likely meant that people whose approaches were incompatible simply agreed to disagree. But more often debates pushed people’s thinking in new directions, inviting them to question what they might take for granted as normal or unnatural about their desires, sexual relationships and friendships.

The writing of founding member Jearld Moldenhauer, especially in the very early issues of the paper, offered a sophisticated analysis of connections between class and sexuality — a concern that permeated much of the paper’s writing over the years. Engaging the theoretical work of Herbert Marcuse and others, his writing incited people to challenge the repression of sexual desire and existing class structures. It would be rare to find analysis of such depth and length in newspapers today. Looking back over the last four decades, Moldenhauer explains, “As the movement grew, the sort of radical questioning element, trying to challenge the structure of society, just lost ground… The Body Politic was perceived as a vehicle to analyze and write about all sorts of sexual-political issues — to get people to rethink their positions on sex and love.”

***

Expression of sexualities

On a very basic level, the political aims of the paper were about coming out, being out and encouraging others to do the same. But the politics of liberation encompassed far more than bringing an end to closetry, especially for those who had previous experience in other kinds of social movement organizing. Many saw sexual liberation as connected to the work of activists fighting against sexism, racism, the systematic violence of psychiatry, the injuries of the class system, and a host of other social injustices. This emphasis on building coalitions with other social movements stemmed, in part, from the influence of Trotskyist political theory. In simple terms, this sort of political vision emphasized the need for ongoing activism, that it would never be enough to focus on the interests of one social group, like homosexuals, to the exclusion of others. Coalitions between different activist groups were necessary to ensure that the movement attended to the needs and concerns of all people. For liberationists who were chiefly interested in freeing society from the shackles of heterosexual dominance, the constraints of the patriarchal family and the fearful life of the closet, it was sometimes difficult to work alongside people who did not share their view of sexual liberation.

Sexual politics was central to the paper, in theory and in practice. Chris Lea recalls the atmosphere of The Body Politic offices and the paper itself. He explains, “The Body Politic was very sexual. There was a kind of fundamental idea that sort of permeated. It was that promiscuity was the glue that kept the gay community together. They used to say that. It’s hard to believe, but they used to say that. So, it made me into a kind of more sexual being, for sure.” For Lea the paper provided an education in how to be open about sex and to make sexuality a political practice, not just at the paper but in other aspects of life as well. He says, “It was The Body Politic that made me political and made me see politics.”

Philosopher and Body Politic collective member Sue Golding has argued that during the years of gay liberation, people understood coming out as a declaration “that the body is political, and therewith, that sexuality is political, ie a constructed source, a focal point, an intersection of power at all levels and in a multiplicity of ways.” As a central tenet of sexual politics, most people involved with The Body Politic understood the need to challenge the status quo of heterosexual dominance and the way rules about normal sex shape our lives.

The majority of people involved with the paper, regardless of their specific political and theoretical views, felt that sexual liberation was part of a larger web of activism. The question of how to rally support and bring about change in people’s attitudes toward sexuality meant working with, rather than against, different communities. Approaching desire from an angle somewhat different from Golding, long-time collective member Ken Popert nonetheless sees power at work — not as something that produces desire, but as an essential aspect of how to mobilize politically. He describes his belief in a vanguard left that needed a critical mass to support its work. His understanding of sexuality is as “a pristine impulse, and our major task was to restore that.” If liberationists wanted to bring about significant change and to liberate desire from repression, they would need to rally support in large numbers.

One of the most vigilant advocates for building connections between groups and across lines of difference is collective member and lifelong activist Tim McCaskell. As someone who worked on international news, the breadth and scope of his analytical writing often looked at how interlocking issues of race, class and sexuality affected people’s everyday lives. He finds that the work of queer community mobilization was in certain ways clearer during the days of gay liberation. He explains that during the ’70s, “class differences were not so acute. You might be a bit richer or a bit poorer, but most of us had to deal with the same discrimination, the same marginalization, the same cops, the same queerbashers. There was a centre of gravity in the middle and our common sexual orientation could bridge what other differences there were.”

***

Engaging community

The problem of coalition politics plagued the paper from the outset. The late Herb Spiers described tensions within the collective in the early years of the paper about the inclusion of lesbian content as symptomatic of a larger problem of sexism. He recalled that some men “thought that it was lesbians’ job to teach gay men about their lives and issues.” In an effort to educate men on the Body Politic collective, women organized consciousness-raising groups. The gender divide relaxed somewhat as the years moved on and more women got involved. Chris Bearchell, a mainstay through the late ’70s and early ’80s, played an active role in encouraging friends, lovers and other women to get involved. She was an exception to the rule, not because she was a woman mostly among gay men on the collective, but because she dedicated so much of her work to fostering connections among feminists, liberationists, sex workers, union activists and marginalized social groups.

The question of how to reach people was always a concern for those at the paper. Gerald Hannon was involved from the second issue until the paper folded in 1987. His take on The Body Politic’s commitment to extending its reach emphasizes that the paper was quite different from lifestyle magazines available at the time. As he puts it, the paper’s perception of gays and lesbians was as “a nascent community of interest, not a community of consumers, which is how many gay magazines would have seen you.” In Hannon’s view, it was summed up in the shared belief that “people in the community had a lot to learn from each other, and The Body Politic could facilitate that.” The key to advancing the work of sexual liberation was to avoid becoming insular or self-serving, and to find ways to reach people who were not card-carrying liberationists. People like Bébout were quite skilled at doing this sort of work. According to Hannon, “Rick Bébout became one of the most powerful people in the paper, partly because he was good at everything he did. He was community oriented, with a strong sense that we weren’t just producing this for a cadre of deeply involved gay activists, but that it had to be for a wider community, and that we had to build that community.” Just how that community would be created and transformed was never totally clear, and the paper often had difficulty pairing the sexual liberation agenda with other social issues and other forms of oppression. Indeed, this made for a rough ride when issues of sexual freedom won out over other issues of concern, particularly when feminist and anti-racist politics were put on the table next to liberationist concerns.

Looking back over the last 40 years, so many of the people who were central to gay liberation organizing and to The Body Politic have passed on, many from HIV/AIDS. There is an obvious danger in forgetting the struggles of those who went to the wall in fighting for sexual liberation. But there is an equal danger in misunderstanding their efforts as fixed on a limited set of achievements.

The paper was a social experiment, an intellectual engagement, and a political project aimed at changing the world. In this way, it was a working out of difficult issues, sometimes messy and fraught with contradiction. There is so much to be learned from the work of the paper, from the rousing ideas laid out in its pages to the incredible individuals who gave so much of themselves to all of us.

Michael Connors Jackman is a PhD candidate in social anthropology at York University. His research focuses on media activism and queer history in Canada.

—

Our series on PTP’s 40th anniversary….

- The Body Politic by Michael Connors Jackman

- Meeting my life by Gillian Rodgerson

- An education by Peter Knegt

- Seeking our history by Gerald Hannon

- Moving boldly forward by Michael Pihach

- Our work today by Xtra staff

- A timeline of events in PTP history

- Pink Triangle Press 40th anniversary party

- The 1981 Toronto bathhouse riots

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra