The first woman I really loved was a feminist anti-porn crusader. Our dates included the Take Back the Night march and Lesbians Against the Right events, and her idea of a love letter was a copy of a political essay she’d written, dedicated to me. Being a lesbian seemed to involve an awful lot of meetings… interrupted occasionally by demonstrations.

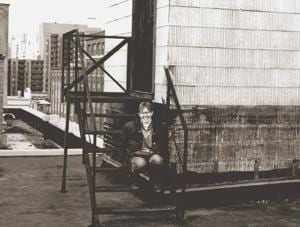

Gillian Rodgerson on the roof of The Body Politic office, 1983. Credit: Courtesy Lee Lyons

In fact, I was going to meetings long before I managed to even kiss another girl. In the spring of 1979, I belonged to Gay Youth Toronto (GYT). The meetings, held at The 519, were usually attended by me, one other young woman, named Helene, and a lot of guys. I was 18, and apart from my fellow GYT member, the only lesbians I could find were in the card catalogue at my local public library: Gertrude Stein and Virginia Woolf were my pin-up girls. I really wasn’t looking in the right places. Then, in May 1979, the Bi-National Lesbian Conference came to town. Helene and I were asked to speak at a workshop on young lesbians. There I was, speaking fairly confidently on a subject I knew about only in theory… One set-up blind date later, an evening at the Jane Chambers play A Late Snow, and still no kissing, but at least I’d seen a lot of lesbians, including the ones on the stage. I remember sitting on the steps of Trinity-St Paul’s Church, looking at passersby and thinking, “Do they know I’m a lesbian? After all, here I am, sitting here, being a lesbian! With other lesbians!” I was pretty easily pleased and I felt like I was on my way.

It began for me…

When the baths were raided in February of 1981, I was at university in Waterloo, but I still had one foot in Toronto. By then I’d progressed from meetings to meetings and dances and eventually, to working on the Gay Liberation of Waterloo helpline, giving advice and support to anonymous, sometimes desperate, voices on the phone. And, I’d kissed some girls along the way.

I wish I could say that I came to The Body Politic through a burning commitment to gay liberation or as a logical extension of my personal politics, but that wouldn’t exactly be true. Those things developed later. I came to the paper, as many people did, because a good friend was already there, because I liked the people, and because I was looking for a way into the community and the life that I needed to have. In the aftermath of the bathhouse raids, I’d helped my friend Craig Patterson sell copies of The Body Politic at the rally at St Lawrence Hall, hearing Margaret Atwood make her famous remarks about how shocked she’d be if someone burst in while she was taking a bath. And slowly, over the next year or so, I moved away from Waterloo, fell in love again (this time with a woman who couldn’t stand meetings and preferred photographs to endless words) and returned to Toronto. In those days, for me and for my friends, being gay and fighting for gay liberation were synonymous, in a way. Demonstrations and groups were where we met our friends and our lovers. There was a lot that needed changing, and it didn’t occur to us not to take it on. Reading and writing and talking, always talking, were the ways we made sense of the identities we were trying to assume: lesbian, feminist, gay man, socialist.

Sort of accidental though my arrival there was, The Body Politic ended up giving me my queer life. I wrote a book review, then a little news story, both edited by the late, wonderful Chris Bearchell with the kind of seriousness and deep attention that she paid to everything she did, large or small. More talking, sometimes arguing, sometimes just hanging out over dinner and telling stories: over the course of a conversation that lasted for years, I fell a little in love with her, too.

It was Chris who suggested that I work with Tim McCaskell on the international news desk, and from Tim I learned to look at the world with my eyes more open than they had ever been before. We wrote about struggles in Eastern Europe, in Africa, in Latin America and in the United States. Each new gay group that emerged in a country where there had been only isolation was a cause for celebration; each setback an outrage, and there were a lot of both. Some of those stories are still going on, or are just concluding now, nearly 30 years later. We wrote about the emergence of a new epidemic amongst gay men, and we tried to make sense of the science that we suddenly had to absorb.

The legacy

The Body Politic wasn’t always an easy place to be: arguments were passionate, and because most of us worked so hard, the paper was our social life as much as our workplace. Women working on the paper sometimes faced suspicion and criticism from other dykes: why did we work so closely with men? How could we support some of the things the paper was assumed to stand for? Why didn’t we give our energy to a project solely for other women?

Why did I stay? I stayed because I found a group of people from whom I learned how to think, how to write and the power that our words could have. None of the pretence of “objectivity” for us: as long as we were fair, we were blatant about our agenda of persuasion. We recruit? Damn right! You treat us badly? We’re going to expose you as the idiot that you are! Not all of the best things about The Body Politic made it into the pages of the paper: in person, we were much more amusing than we probably were in print, and the love and loyalty that most of us had for each other wouldn’t have been obvious, either. But, I still feel it. And all of the work I’ve done since then — writing international news forGay Times in England, editing Capital Gay and Diva magazine, working with Feminists Against Censorship and Outrage! and Amnesty International — comes directly from what I learned there. Even now, when I’m thinking my way through some project, I hear Rick Bébout’s voice in my head asking, “What’s it for?” because knowing why I’m doing something will usually show me how to do it.

And, as activists have known for centuries, the exhilaration of being a part of something bigger than yourself and the sense of comradeship that comes from a common purpose is incredibly sexy.

Gillian Rodgerson joined The Body Politic collective in 1983. Today she sits on the board of directors of Pink Triangle Press and works as a book editor.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra