Let me begin with a death. Let me begin with a sentence I wrote on the last page of the last issue ofThe Body Politic, “a magazine for lesbian/gay liberation” (the forerunner of Xtra). That issue, number 135, was dated February 1987. It was the last issue not because we were bankrupt (though we were on the edge) or because the police had hounded us out of existence (though they tried). The reasons were many and complex, but in our world-weariness and exhaustion that year closing the paper down felt inevitable. I wrote on that final page that, though we hoped one day to bring something new into the world, “I feel now that nothing again will ever be so new and fresh and young and eager, so pigheaded, so infuriating, so clumsy and so young.”

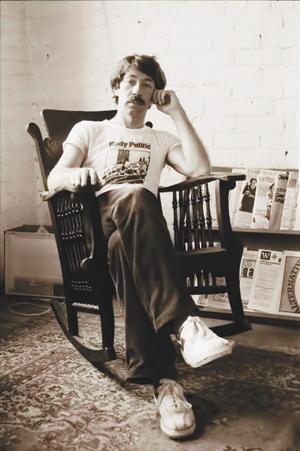

Gerald Hannon in the Duncan St office of The Body Politic. Credit: Courtesy of Gerald Hannon

I had a reason to feel passionate and bereft — I’d worked on every issue but the first, which was dated November/December 1971. The Body Politichad been my job and had consumed my life for 15 years. And then, suddenly, it was gone. And then, suddenly, I was 42 years old and had to reinvent myself on the brink of middle age. I wasn’t very hopeful, either for myself or the prospects for gay publishing.

History proved me wrong. Oct 27, 2011, marks the 40th anniversary of the day the first issue of The Body Politic went to press. Its children — the media conglomerate that is Pink Triangle Press — rule gay publishing in Canada. The Press is almost embarrassingly successful. With yearly revenues of more than $9 million, and more than 65 employees headquartered in more than 14,000 square feet of office space on the 16th floor of a building at Yonge and Carlton in Toronto, it has interests in print, television and online media. The Press makes a profit — it has to. The money doesn’t go to shareholders, though — it becomes seed money for new enterprises or gets ploughed back into the community. That was the model at The Body Politic. It still is.

I am the vice-president of the board of directors of the Press and its longest-serving member. I see how far we’ve come. In the best ways, though, I see that we haven’t changed much at all.

How far we’ve come

I look around the office today, and I see mostly young faces, and I remember that the Press was started by kids — at 27, I was the oldest member of that founding group. We were kids who didn’t know anything about journalism, or publishing, or accounting, or advertising sales, kids who met in each other’s apartments, who believed in collective decision making despite its sometimes near comical inefficiencies (for the first few issues, articles were approved, or not, after being read aloud by the author, which meant, given the potential for embarrassment and ill will, that near everything got approved). The kids I see today are impressively skilled and know a lot more than we did. They have to. The world has changed. But they’re passionate, know they don’t know everything and know they have to learn. That hasn’t changed.

I look around the office today and I see shamelessness. The art work on the walls is unabashedly erotic and political. The video arm of Pink Triangle makes delicious little fuck videos as promo for squirt.org. I remember that the press, 40 years ago, fought for the sexual emancipation of the young, championed drag, shone a spotlight on the erotic needs of the disabled and played shamelessly with the erotic potential of office life (I remember the men in the office queuing up on the roof to fuck some guy who came in off the street, begging to be fucked. I remember another night when, after everyone else had gone home, I tried to push a broom handle up my ass because I was so horny. In deference to current pieties, I should add that it was a consenting broom handle).

I look around the office today and I see women. I see a lot of them —they are about 30 percent of the Press at the employee level, higher among the members of the board. I see trans people. I see people of colour. I see progress — I remember that the Press, in my day, was almost entirely male and very definitely entirely white. But even then, collective members like Christine Bearchell and Tim McCaskell never stopped reminding the rest of us, mostly university-educated, white, middle class men, of how smart it was to try to build a movement that reached out to allies in other communities. I remember how that paid off big time during crises like the 1977 police raid on The Body Politic and the subsequent criminal charges — the arts communities slowly emerging along Queen West were among our first supporters (visit the General Idea retrospective at the Art Gallery of Ontario — it’s the best show in Toronto — and realize that that smarty-pants collective was just a bunch of local goofs, like us, back in the ’70s, and were among the performers at a support rally held just before The Body Politic trial began in 1979. The then-mayor of Toronto, John Sewell, also attended that rally and voiced his support. Read that these Ford-ster days, and weep).

An enduring mission

“What came before is foundation, inspiration, a lesson and a warning. We seek to own our history: we learn and teach and guard it.” Those are the last two sentences of the Press mission statement, a document I helped devise. I’ve been in the privileged position of seeing our history unfold over the last 40 years and, for some of that time, have had a hand in guiding it. History became part of our mission because we discovered, to our surprise, that we actually had a history. Back in 1971, many of us thought we were the first homosexuals ever to make a claim for justice and acceptance. It was revelatory to discover, in a groundbreaking series of articles we published in The Body Politic, that there’d been a thriving gay movement in Germany until it was crushed by the Nazis. It was revelatory, and a warning — Berlin had had both a varied commercial gay scene and organizations working to change anti-gay laws. A few years later, many of those struggling young men and women were in death camps. That was a hard lesson. It was good to learn (we can all share that history now, and the many histories that followed and preceded it, thanks to the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives, an organization started by The Body Politic).

“We seek to own our history: we learn and teach and guard it.” Owning, sharing, teaching, guarding. Forty years have taught me that history never stops, even when our bodies do; that history never stops, and we can shape it. I can look back now over 40 years and smile at my naiveté in 1987. Things still glisten.

Gerald Hannon did manage to reinvent himself, in the wake of the passing of The Body Politic, as a successful freelance writer and sex worker.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra