When Xtra first launched in Toronto in March of 1984, it wasn’t the politically minded news source you know today. It was more or less a party and community guide, a lighter alternative to the political, radical, intellectual, serious tone of The Body Politic.

“Xtra was an attempt to be more popular than The Body Politic,” says Ken Popert, Pink Triangle Press president and executive director. It was initially distributed as a compact, foldable pamphlet. “Something free that people could stuff in their pockets.”

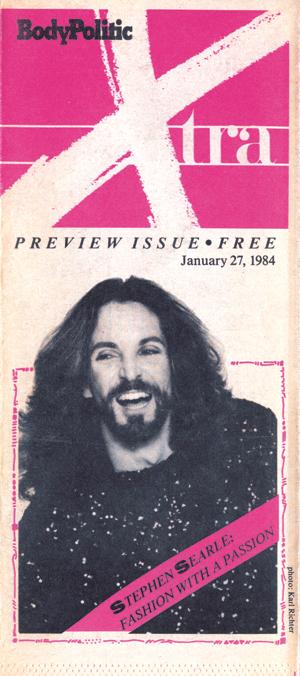

The very first edition of Xtra, in 1984.

Xtra’s early Toronto editions brimmed with gay party listings, personal ads and advertisements for the popular gay bars of the day, such as Chaps and Colby’s. It had a flashy, hot-pink design and eventually began publishing accessible stories with a much broader appeal.

“People called Xtra a clone paper,” says Pink Triangle Press publisher and editor-at-large, David Walberg, who started at Xtra in 1989 as a part-time production assistant. The clones in those days were the mustache, tight jeans and bulging package set.

“It was the dawn of desktop publishing,” recalls Walberg. “We had just bought a Macintosh computer that cost, like, $10,000. We developed our own photos. We had a darkroom.”

Xtra grows up

After The Body Politic folded in 1987, and as events transpired and times changed, Xtra grew and adapted. In 1993, as revenues began to roll in to Pink Triangle Press from its telephone hook-up service Cruiseline, two more editions of Xtra hit the streets: Xtra West in Vancouver and Capital Xtra in Ottawa. Together they reported on the political battles of the 1990s and 2000s: the defeat of the Ontario NDP’s Bill 167, which would have granted spousal rights to same-sex couples; the raids at Remington’s, the Bijou, the Pussy Palace and Goliaths; the censorship battles of Little Sister’s and Glad Day bookshops; the murders of scores of community members, same-sex marriage and, more recently, the debate surrounding the criminalization of HIV/AIDS.

During Canada’s most seminal queer times over the last three decades, of which only a few are mentioned above, Xtra was there, notepad and pen in hand, reporting and conspiring on issues of huge import to gay and lesbian Canadians. It’s the paper’s contemporary approach to activist journalism that earns it a love/hate relationship with some of its readers. Xtra’s management knows that and eagerly points out that the paper is fuelled by a political agenda of activism and sexual liberation, not a desire to make money on the backs of blissfully ignorant readers.

“It’s our job to make people uncomfortable and poke them in the eye,” says Popert. “We encourage people to be self-critical.”

That’s true even — or maybe especially — if it means criticizing people and institutions within Toronto’s gay and lesbian communities.

The 2011 Toronto Pride edition.

“Gay and lesbian people deserve to know what’s really going on in their communities,” says Matt Mills, Xtra’s associate publisher and editorial director. “As part of its work, Xtra tries to ensure that gay and lesbian community organizations, and the people who lead them, are transparent and accountable to gay and lesbian people. It’s not about being mean or tearing people down, it’s about ensuring frank and open discourse. No question is off limits in Xtra’s pages, no matter who or what is at issue.”

What does the future hold for Xtra?

“Community newspapers are niche publications that give readers something they can’t get elsewhere,” says Xtra’s publisher and editor-in-chief, Brandon Matheson. “Even though the mainstream press has more gay and lesbian content than it used to, it doesn’t do the job as effectively as the lesbian and gay press does. No one newspaper can be all things to all people. That’s a false premise.”

An extended version of this piece, “Why Does Xtra Do Some of the Things It Does,” was published in the Toronto edition of Xtra in June 2009.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra