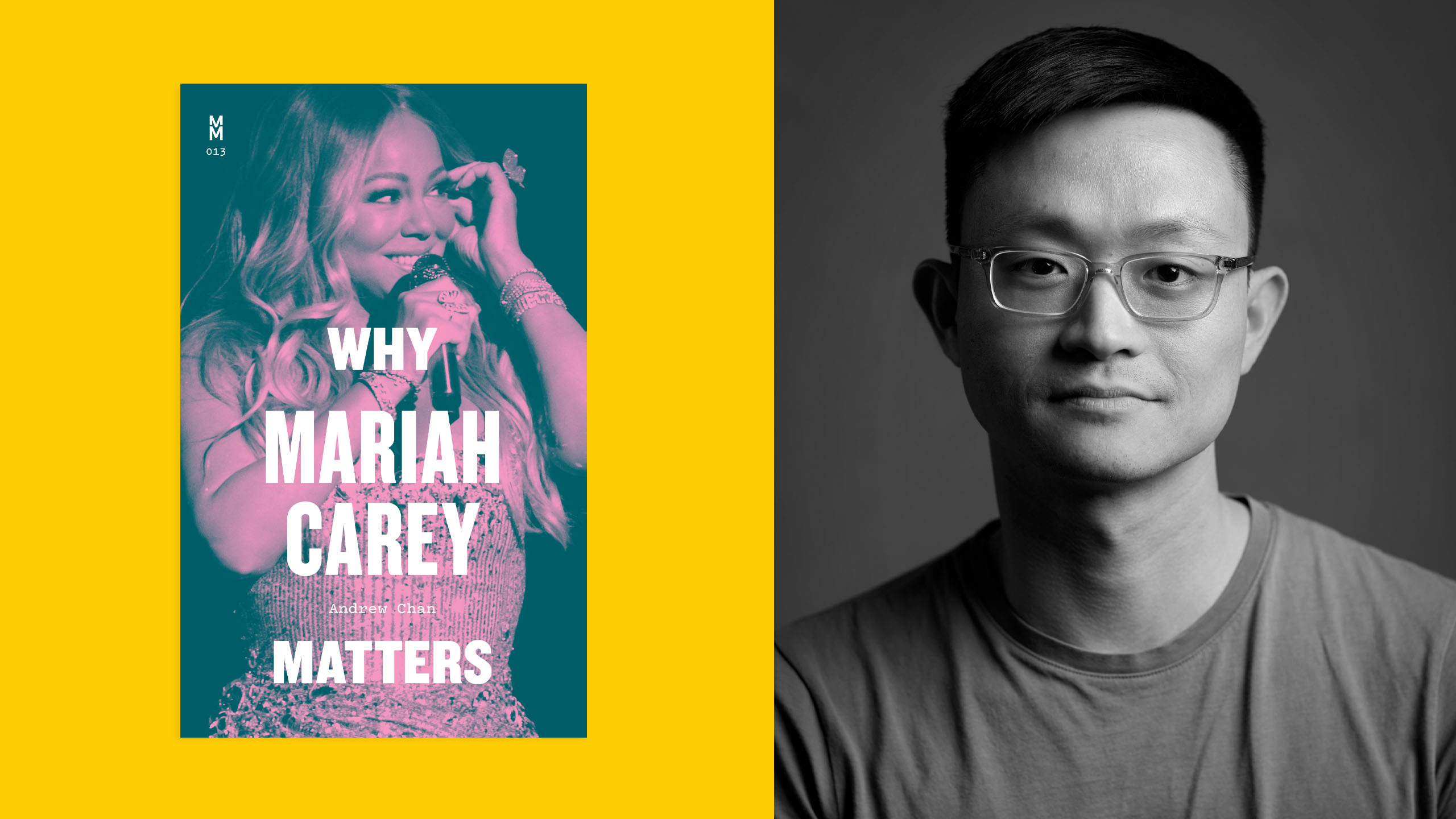

In an era where record labels are struggling to craft the next generation of pop stars, author Andrew Chan dissects what it means to be a true diva in his new book, Why Mariah Carey Matters.

The 145-page monograph critically examines the evolution of Mariah Carey’s career, musicianship and indelible influence on the music industry, while putting into context some of the circumstances and politics that surround the Songbird Supreme’s life as a mixed-race woman who has sung, written and produced some of the biggest hits in music history.

While Chan quickly establishes himself as a diehard fan—or, in this case, lamb—make no mistake, these are not the ramblings of some obsessed groupie (I would know as a journalist and lifelong fan myself). Instead, he offers a level-headed analysis of his idol’s life and career, which at times includes a few critiques of Carey’s shortcomings.

This is Chan’s first book after dabbling in arts criticism for years, and part of a series called Music Matters, which publishes passionate arguments for the significance of a single artist or band. Previous iterations have included artists like Tammy Wynette and the Beach Boys. But what stands out the most about this book is the intimacy of the author’s writing.

Chan plants readers into his childhood and reveals personal details about himself that most authors would typically omit from celebrity books. But Carey’s own writing about life as a misunderstood outsider has helped her forge deep connections with a multigenerational fan base that is spread across continents, and because Chan is someone who grew up between the U.S. and Malaysia as a closeted gay boy in the 1990s, his perspective is particularly noteworthy.

Chan’s confessional writing style is distinctly on display in the first chapter of the book when he begins discussing “Outside,” a song Carey co-wrote with collaborator Walter Afanasieff for her 1997 album, Butterfly. In the song, Carey—whose mother is Irish, and whose father is Black and Venezuelan—pens a personal anthem that gives fans a glimpse into her struggle growing up as a biracial child in the ’70s and feeling like she had no place in the world. The universal message of not fitting in is one that resonates with fans who have faced similar challenges due to their race or identity.

“When you live in a closet, you learn to look out for signs. Signs of danger. Signs of rescue,” Chan writes. “I was 10 or 11 when I first heard ‘Outside,’ and I didn’t realize I was responding from the outside of the song: as a Chinese American falling in love with Black American music; as a nerdy, closeted gay boy projecting his life on to a glamorous, hetero-feminine idol … I felt the connection to be intimate and private—from her heart to mine. Mariah made my outside feel like an inside. I knew if a voice were a place, I’d call hers home.”

In this passage, Chan reveals himself to readers and provides a brief look into his world and perspective. But his writing turns diaristic when he shares a personal anecdote about an older gay pen pal who helped him realize the power of Carey’s more breezier songs like “Heartbreaker” and “Bliss” from her 1999 album, Rainbow.

At the time of the album’s release, Chan admits that he had picked up some prejudices that came between his love for the elusive chanteuse. “In a matter of just a few years, I’d become embarrassed about loving Mariah,” he writes. “As a kid who sometimes went to nauseating lengths to act older and wiser than my age, I’d internalized the message that certain kinds of music deserved more attention than others—and that it wasn’t worthwhile to take artists like Mariah seriously. I began gravitating to Fiona Apple, Sinéad O’Connor and Tori Amos, confrontational singer-songwriters who had it in them to say ‘fuck you’ to the world more belligerently than Mariah ever would.”

The question surrounding the seriousness of Carey’s musicianship during this period was also raised by critics and industry bigwigs who dismissed her music as “crossover fluff.” But it was a defence by that pen pal, whom Chan met in an online chat room about pop divas, who helped him expand his understanding of what matters.

“In retrospect, I like to think my pen pal was teaching me, in his own indirect way, that escapism was key to any great diva’s relationship with her queer fans—and that, ultimately, the fear of what’s being escaped is never all that far from view,” he writes.

In the last few pages of the book, Chan revisits these conversations, this time older, wiser and with more awareness of himself. “When I think about the elder pen pad I met on that listserv in the late ’90s, I wonder what we might have been trying to say to each other about our lives in all our appraisals of favourite singers, correspondences in which the topics of sexual identity, homophobia and heartbreak were, as far as I can remember, never once broached,” he writes. “Just as opera and Broadway have served as secret languages within segments of the gay world, I suppose the vernacular of pop and R&B divadom became for the two of us a kind of Morse code. That’s why, even now, an encounter with Mariah’s music can sometimes feel to me like a rendezvous with the closet, and with the emptiness I needed her voice to fill.”

These heartfelt excerpts where Chan exposes the ambivalence he feels toward his sexual identity and dissatisfaction with Carey’s music during the Rainbow era are just a few instances where he divulges himself to readers. But through it all, Chan maintains his love for Carey; that’s why it’s understandable that his analysis at times feels defensive, because, as he points out, it’s in his nature as a member of Carey’s fandom, the lambily.

“These days, the adoration Mariah receives from the lambs is tinged with protectiveness, fuelled by the idea that her achievements are in need not just of praise, but of vociferous defence,” he writes.

That protectiveness comes into play as Chan attempts to answer a central question of the book, which is, how can someone as successful and influential as Carey still be so underappreciated by critics and casual listeners who may only pay attention to the singer during the Christmas season?

Much like her bestselling memoir, The Meaning of Mariah Carey, Chan rifles through Carey’s discography, album by album, to tell her story. He walks us through her decades-long career, from the “Cinderella moment” when then 18-year-old Carey handed her demo tape to the chairman and CEO of Sony Music, Tommy Mottola, at a Manhattan party in 1988, up until her most recent deified status as the Queen of Christmas. In doing so, Chan analyzes her vocal anatomy, dissects the meaning behind her lyrics and exposes some of the battles she faced within the music industry and her own personal life.

At the beginning of the book, Chan reflects on a specific career choice Carey made in the late ’80s when she turned down an invitation to audition for the iconic hip hop record label, Def Jam. Instead, she would later sign with Sony Music and while some may say the rest is history, Chan can’t help but wonder about the politics at play: “What would Mariah’s early music have sounded like if she’d started out at a smaller label with lower financial stakes, a commitment to Black music and a youthful roster?”

Under Sony Music, Mottola was willing to spend millions to launch Carey’s career (which also made her a target for critics), but his “lack of the usual MBA pedigree” led to professional insecurities that made him opposed to taking creative risks. He envisioned Carey’s career as a “Ballad Queen,” singing songs that would broadly appeal to white audiences between 25 and 50. But as Chan points out, Carey’s own tastes were aligned with the Black styles of music that Mottola discouraged her from pursuing, and this conflict only heightened the pressures she faced as a mixed-raced woman in the music industry.

The 1990 release of Carey’s self-titled debut album, and its successor, Emotions, amassed a wave of success, including a Grammy nomination for Producer of the Year (Non-Classical). While she may have stunned listeners with her wails, growls, whistles and lightning-speed runs, Chan says critics were still eager to single her out: “For some, Mariah was just another major-label cash cow watering down Black music and hastening its decline.”

The topic of Carey’s race and the struggles she faced because of it are a central theme in the book and come into focus over the evolution of her career as she works to affirm her music in its Black roots. Despite much of Carey’s repertoire being perceived as adult contemporary pop ballads, Chan describes her songs as genre chameleons that don’t fit neatly into one music category and are tinged with pop, R&B, gospel, soul and hip hop.

Although Chan provides fans with more insight into the pressures Carey faced and the backlash she received from the music industry, his book isn’t intended to be a tell-all. At 145 pages, it pales in comparison to Carey’s 350-page memoir, and its brevity makes it almost impossible to fully assess a career as massive as hers.

While there are a few juicy tidbits like industry snubs and a few sentences about a rumoured feud between Carey and long-time collaborator Walter Afanasieff, the book doesn’t go deep into the weeds and at times appears apathetic to the gossip, even when there is the possibility for more exploration.

For example, in reference to Carey’s feud, Chan simply writes that Affanasieff “had been the man behind several of Mariah’s hits, but for reasons that have never been fully disclosed, their relationship was fraying beyond repair.” Then later in the book, returns to Affanasieff, but only for a brief moment to mention how he was “swapped out” for Hollywood hitmaker Dianne Warren, but that is the last we hear of him, even though there is more to the story.

Take, for instance, an interview that Affanasieff did with RadioTimes.com in 2018, where he bitterly bashed Carey for dismissing his input on their hit, “All I Want for Christmas Is You.”

“She doesn’t like to acknowledge other people,” he explained before calling her jealous and insecure over his work with other artists like Céline Dion and Barbra Streisand. “It doesn’t matter how many interviews she’s done or when she’s on stage, she’ll never ever say, ‘Here’s the song that I wrote with Walter.’”

Moreover, the book makes no mention of Carey’s fraught relationship with handlers like powerhouse celebrity publicist Cindy Berger, who dropped the singer from her client list in 2015, or her turbulent relationship with former manager Stella Bulochnikov, whose 2018 lawsuit is alleged to have turned Carey’s hand into publicly revealing that she lives with bipolar disorder.

While these stories are minuscule in the grand scheme of Carey’s life and career, they could have added more colour to Chan’s book, which mostly relies on research from secondary sources like books and newspapers. It’s unclear what new information readers would gather if Chan had posed questions directly to Afanasieff, Berger or Bulochnikov, but his lack of first-hand interviews becomes apparent as he glances over details that are discussed among lambs and otherwise would have had readers glued to their books.

Notwithstanding the innate gay urge to gossip, there are more queer themes sprinkled throughout the book, including Carey’s foray into the realm of remixes. Midway through the book, Chan explains how Carey found creative freedom and made inroads into the gay club scene through collaborations with DJ David Morales and producers David Cole and Robert Clivillés, the men behind C+C Music Factory.

“House music may have represented the margins for a singer of Mariah’s eminence,” Chan writes. “But to its fans, it was the centre of the universe—and Mariah gave it the reverence it deserved.”

These small love notes to queer readers are dropped throughout the book, but Chan’s focus stays fixed on Carey’s extraordinary voice, her metamorphosis from ambitious ingenue into a showbiz heavyweight and the impact her music has on legions of loyal lambs, the latter of which is most poignantly displayed in the final passages of the book where Chan writes:

“As much as romantic commitment, professional ambition, or familial duty, the sound of a voice can be a source of inspiration to keep on living. I can’t separate my love for Mariah from the belief that her voice has saved lives, including gay ones like mine.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra