I came across Vivek Shraya when I began my Ph.D. dissertation. Shraya’s She of the Mountains (2014) was one of the main texts for my chapter on the representation of trans people in South Asian Canadian fiction. What immediately drew me to her work was the way her unnamed narrator effortlessly embodied a fluidity of gender and sexuality while intersecting with a somewhat queer representation of Ganesha, Hinduism’s ubiquitous elephant god.

As someone still trying to articulate their genderqueerness as well as their bisexuality, Shraya’s novel was a gateway for me to access the vocabulary for who I had always been inside. Since then, both as a part of my doctoral research and my personal interest in her evolution as a writer and artist, I found myself ardently keeping tabs on her work spanning multiple genres—photography, writing, theatre, music, film—invigorated as an emerging writer by her constant reinventions as she represented the trans woman in her works.

Her 2020 sophomore novel, The Subtweet, pushed the boundaries of trans representation even further through the creation of the character Rukmini, whose transness is present but not called attention to. Unlike cis South Asian writers like Anosh Irani, Arundhati Roy and Megha Majumdar, Shraya’s organic, non-voyeuristic representation of Rukmini transcends the obvious trans tropes; themes of trauma, transitioning, gender dysmorphia or bringing constant attention to the character’s trans identity are noticeably absent from Shraya’s narrative.

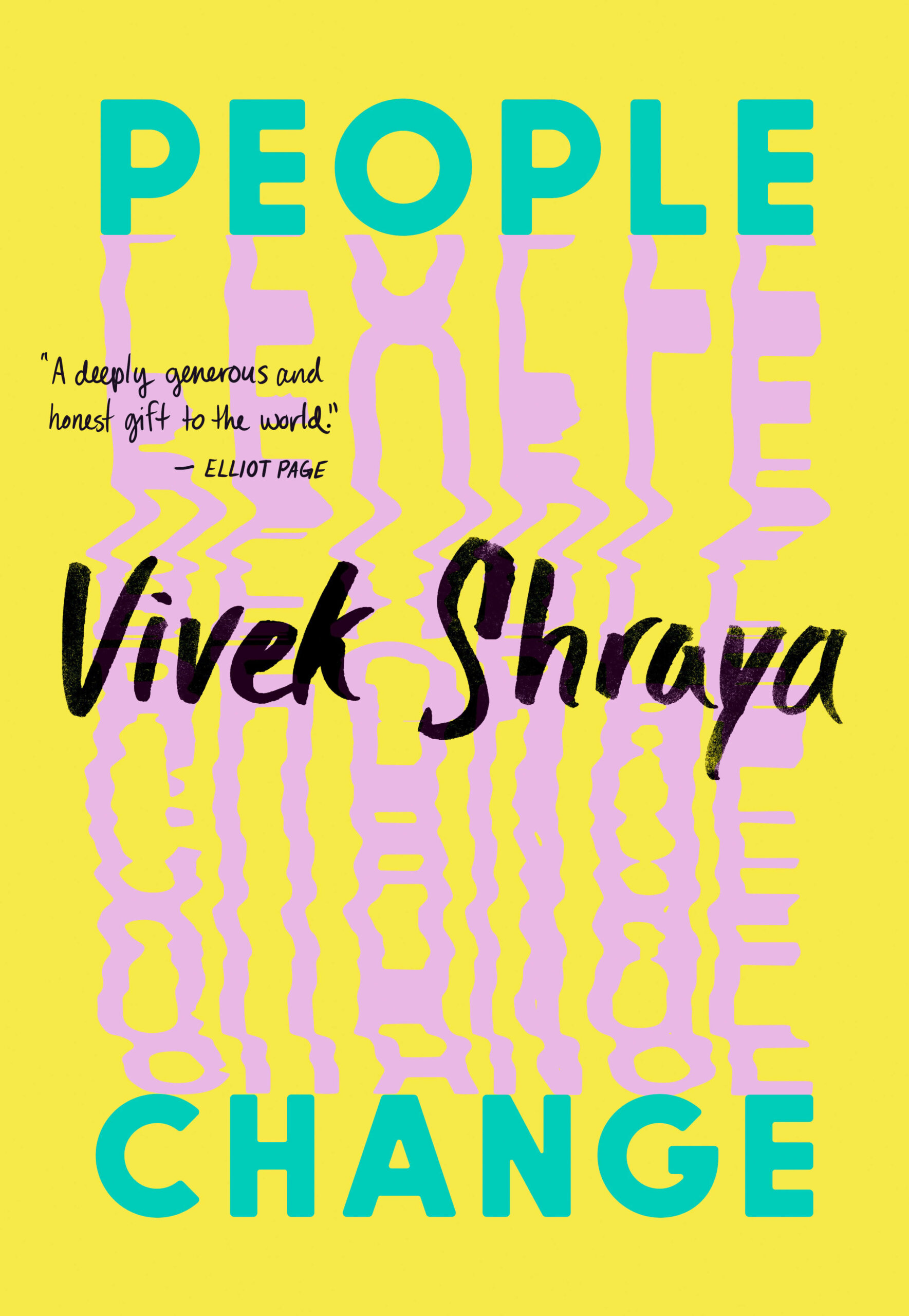

In People Change, Shraya brings together themes she has explored in her multifaceted cultural output over the past decade, with living as a trans woman being at its centre. In this self-revelatory collection of short essays that lies in the intersection between spirituality and queer/trans identity, Shraya examines “reinvention” through multiple lenses and contexts, from Sathya Sai Baba to Madonna. She forces us to self-reflect on our desires for change and question stagnancy through her deepest personal stories and cultural commentary.

Xtra talked to Shraya about her most confessional and radically revelatory book yet.

People Change lies in the intersection of spirituality and queer identity, like your earlier books God Loves Hair (2010) and She of the Mountains (2014). In some places, the themes overlap, like equating the queer self with the divine. Can you speak to your inspiration for this book? Why this book, and why now?

The project originally was supposed to be called “Armour,” and it was supposed to look at the ways in which women or female-identified and gender nonconforming people use our presentations, the way we put ourselves together as a form of protection in the world. I started working on the book, officially, at the beginning of the pandemic. But I found myself really questioning the motivation or the ability to write a book about fashion when we were in the midst of a global crisis. That’s not to undermine the power of fashion, but it was something I really struggled with. And I found that the more I wrote about the exterior, the more it seemed to be about what was happening on the inside. And so I think the book sort of ended up taking a more broad examination on change and reinvention.

To go back to what you were asking, the intersection of spirituality and queer identity overlaps in my work. There’s also a really strong overlap with my play, How to Fail as a Popstar. Right before I started working on the book, I was working on the play in 2019. [The director and I] ended up having conversations about reinvention and my relationship to reinvention. A lot of that got taken out of the play; those initial conversations really planted the seed for this book.

I see the ghosts of all the works that came before in this book. Even though you are reinventing yourself as an artist and your evolution is happening, there’s obviously something that is inherently “you” that you’re thinking about long-term.

One of the things I’ve always struggled with are the ways in which artists tend to “repeat” ourselves. We’re all drawn to similar themes. But marginalized artists are critiqued for it more than white [artists]. I look at Martin Scorsese. In a lot of ways, he’s made the same movie over and over again, but just [from] a different perspective. And I felt so conscious of [this repetition]. But the longer I make art, the more it’s kind of exciting to think about projects being in conversation with each other, and building on top of ideas. It’s very exciting that people are going to be able to, if they’ve engaged with my work before, see the ways in which some of these ideas have evolved and grown. So, yeah, it’s definitely something that I’ve felt subconsciously insecure about, that I’m trying to embrace the ways that you build off of each other. And ultimately, as much as there are times where I’m like, “No more writing about your mom,” or “No more writing about Sai Baba,” or whoever it is, these are things that haunt me. To use your language of ghosts, these are ghosts in my life, right? There’s a part of me that is sort of reconciled to the possibility that they might be my ghosts forever.

You write that in Hinduism, our bodies “are mere shells and our soul aches to be free. This is where homophobia and religion strangely, dangerously overlapped. Both implied that there was something inherently wrong with me, and that reformation could be accessed only through death.” Can you elaborate on what you mean by that?

I’m speaking to my childhood analysis of Hinduism and growing up with very devout parents. It’s never about what you’re doing now—the present only matters insofar as how it connects to the future. The future goal is liberation, or moksha, right? What you want is to be free of your body. I think there’s something really interesting about the ways in which I was learning at home—your actions, any time you do something negative, you’re somehow setting yourself back. You’re constantly being critiqued, and whether or not you can reach the final goal has to do with every single action and word. Even your thoughts matter. And similarly, I think that homophobia, what I was learning in school, was that also that my actions, words and thoughts mattered, and in ways that I didn’t even understand. One of the first times I asked somebody why I was getting called “fag” all the time, they said, “It’s the way that you use your eyes.” And I remember at the time being so, so undone by this revelation. I couldn’t imagine it, a young teenager, trying to figure out what is it about the way I used my eyes that screamed “gay.” And so there’s something about my experiences of homophobia at a very young age; I was abnormal and I shouldn’t exist. And again, my childhood impression, or translation of reincarnation, and Hinduism, was that [my] body shouldn’t exist.

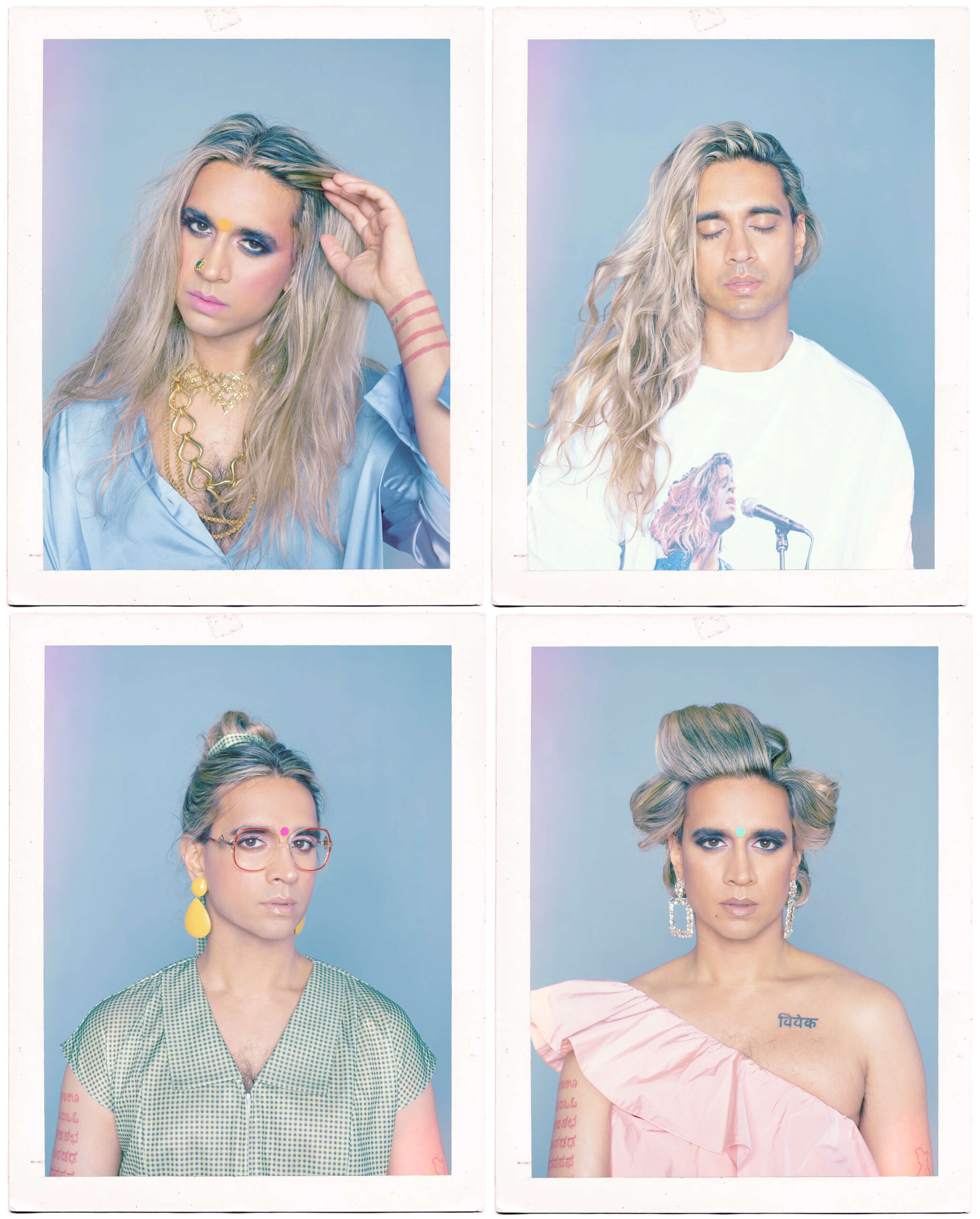

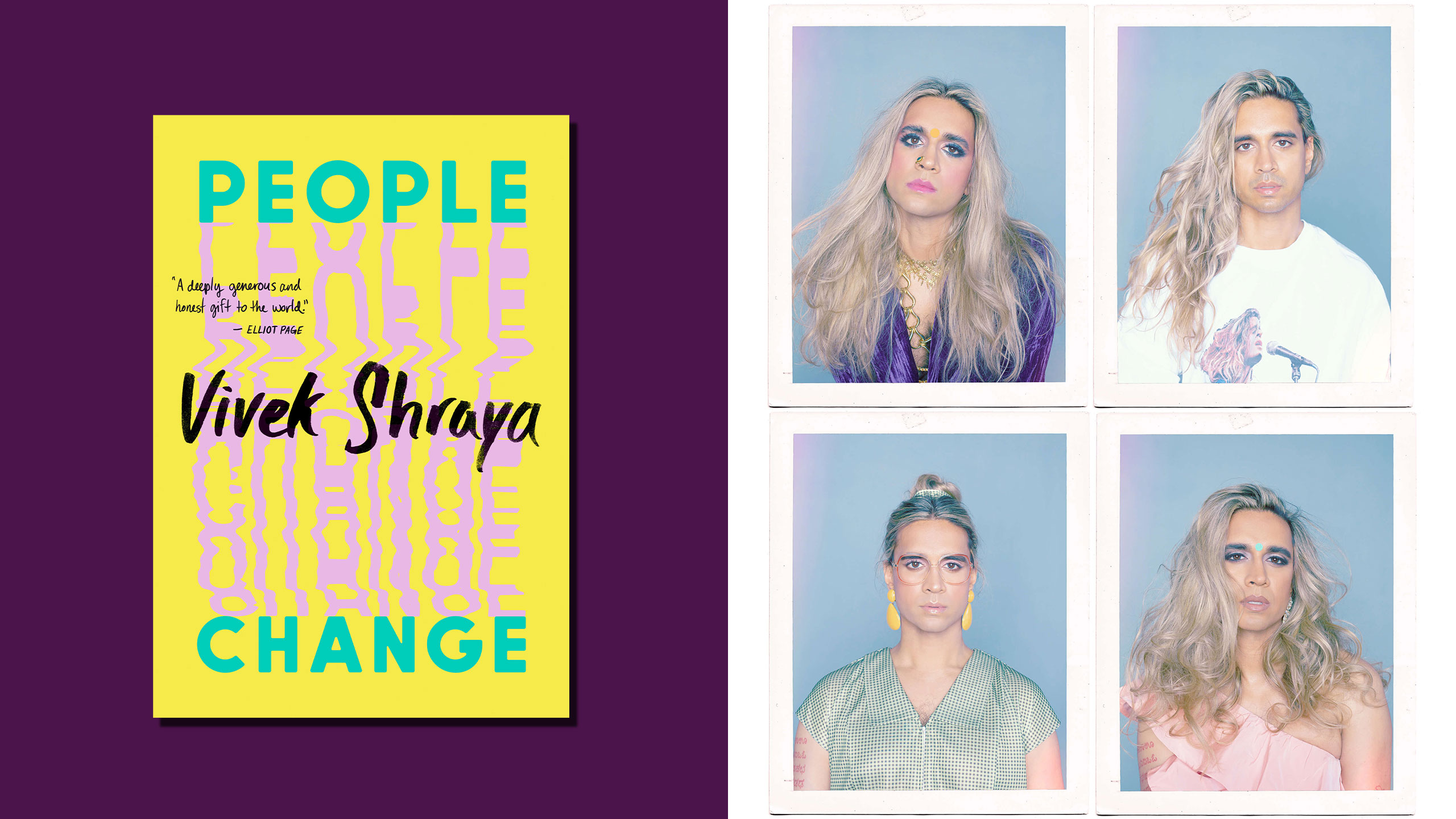

You write that to transpose someone else’s aesthetic onto yourself and create something new is “like a style Frankenstein.” You have four different photos on the back cover with four different aesthetics. Can you speak to that physical aesthetic of transposing someone else’s aesthetic onto you and creating something new?

On a superficial level, I love fashion, and I’m really interested in putting myself together. But I think there’s something really exciting about the ways in which changing your appearance or attire or look can reveal something new about yourself—not only to yourself, but to the outside world. I am constantly learning things about myself every time I explore a different aesthetic. It’s not just about mimicking—mimicking is sort of seen as a negative, culturally. But I draw a lot of inspiration from a range of artists, including Beyoncé and Madonna. And it’s not about being them, per se, but how does it feel invoking that kind of energy? It opens you in a different way. I don’t know how much of this goes back into religion. In Hinduism, one of the interesting things is you’re presented with myriad different gods and different aesthetics, and my understanding of that as a child was that it gives you many entry points, and your relationship to one god or another brings a certain kind of energy out of you. It goes back to this idea that I grew up with, that the body is just a shell and to think about how to use the body, the exterior, in multiple ways instead of just a singular way. For so long, I really saw myself as just a musician, but I’ve learned more things about myself by being able to be creative in other ways and build community through those different kinds of ways.

Keeping with the idea of aesthetics, you write about adopting “Miss” before your name so that you’re referred to as “Miss Shraya.” Miss becomes “a talisman,” much like your teaching uniform—a white dress shirt and black leggings—became a talisman when you were teaching writing at the University of Calgary. Can you speak more to these deliberate adoptions?

When I first started teaching, I was really nervous. The classroom for me is very much the site of trauma, and it’s where most of the homophobia and misogyny that I experienced as a child happened. I never changed my name when I transitioned, which is not a necessity but certainly a rite of passage for a lot of trans people. But for me, giving myself the prefix “Miss” in the classroom felt like a gesture in that direction, where I felt it allowed me to reclaim a kind of femininity that I didn’t get to access. But it also reframes who I am, in a different way, in the classroom. And so, it was kind of an experiment, to be honest. I wasn’t really sure how the students would react. And, it’s been incredibly healing to teach in the province that I grew up in and have young people use my name “Miss Shraya” in the classroom. Part of it is that everyone wants a name. But at the same time, I think it is genuinely coming from—for the most part—a place of wanting to respect who I am in the world. It also allows me to sort of separate a particular aspect of my work. I love teaching, and I feel very passionate about it. But I’ve seen the ways that institutions can essentially hijack your life if you don’t create boundaries. This name has also allowed me to create a boundary between that particular kind of work.

Even when I tour, I usually have a tour uniform. So whatever project I’m touring, I like to have a uniform, because it just means having to pack less. But I do think that there’s a specific kind of gaze, and also expectation on trans feminine people to portray a certain kind of high femme aesthetic all the time; it’s kind of tedious. Embracing a uniform allows me to breathe a little bit, to not take on that pressure. As cliché as it sounds, some of it’s also about safety, right? When I travel to campus and I’m taking public transportation, I can blend in a little bit better if I’m wearing leggings and a white T-shirt than if I am wearing a long dress.

Credit: Ariane Laezza

You write about the “perplexed gaze”; how by being at the front of the classroom, your job “inevitably involves being looked at, but when you’re gender non-conforming, you’re also prey to a particular kind of omnipresent fixation, a perplexed gaze.” Can you elaborate?

The most common microaggression that I experienced as a trans feminine person is staring. It sounds really minimal, probably on the lowest part of the ladder or whatever. But after a while, it really starts to take a toll. When I’m on stage, I want people to face me. But when you’re doing your job or when you’re out and about, there’s a particular kind of way that people look at you. And sometimes it’s just curiosity, sometimes it’s even admiration. But often, it’s confusion. It’s something I definitely encounter in the classroom, especially on the first day of school, and sometimes it’s not even in the classroom but when I’m walking from my office to the classroom, in the hallway, people doing the staring thing. I’ve learned to be hyper-conscious of that kind of gaze because that kind of gaze can sometimes lead to other forms of violence.

I am interested to know more about your idea of how reinvention can subsume pain. When someone is reinventing themselves, they can use pain to become someone new. Can you speak more to this idea of transformation?

When I think about popular uses of reinvention, so much of it is centered around capitalism, a new, improved and better version of yourself. In that context, there isn’t a lot of room to acknowledge the hardship that you’ve gone through to become that person, unless you wield it in a weird capitalist way. One example is the way we celebrate weight-loss photos; the way it’s popping on Instagram, some of it feels to me, as an outsider, kind of performative. For me, reinvention should have space to hold who you were, who you are and who you will be next. I have found that often when I am going through a transition phase—I’m using “transition” broadly—those are the hardest times. I have always found those are the hardest times to access support, because culturally, you are not supposed to reveal [your hardships].

Let’s talk about the malleability of gender. You write, “sometimes I have called myself a trans woman because I know that this will be clearer than saying trans feminine person of colour or even just trans. But which one am I? Gay? Queer?…Trans woman? Trans femme? Non-binary? I am whichever makes sense for the particular moment and social context I’m situated in. I am all of these identities and none of them.” Can you expand on the dynamism of gender?

Since coming out as trans, I have experienced a certain kind of pressure to at all times embody a very mainstream understanding of “trans woman.” The more that I look back at any of the identity labels I have embraced, embracing them has been secondary to the oppression I have experienced. I don’t know if I would have embraced “queer” as an identity label if I hadn’t experienced homophobia. That section is the scariest thing I wrote because even within the queer and trans communities, there is such a pressure to uphold these identities. One of the reasons this section made me nervous is because I really can’t stand when people from dominant groups, like cis people, straight people, white people, say stuff like, “Who needs labels? We are all human.” I hate that argument so much because it refuses to recognize the disparity of power and privilege, and it also makes the person less accountable. But as someone who’s occupied many different identities at this point, I see the ways in which these labels also ultimately limit me and hold me back. As much as queerness is supposed to be about a kind of fluidity, what I have found in queerness and often in queer communities is a kind of rigidity.

For you, reinvention is relationally “tethered” to how it’s received by others. You write, “Every time I present a new version of myself, those around me are also called upon to change.” It’s almost like a ripple effect.

That’s a really great way of reframing that. It’s very much a ripple effect. In my life, there’s been so many times when I’ve wanted to make a change but I’ve been held back by the ways in which the people around me, including loved ones, want to see me or want to hold me. As a settler, I feel very privileged that I’ve been able to move across this country. But I often feel like even moving away from Edmonton, which is where I was born, was essential for me to grow into a new version of myself. Because after 19 years of being in the city, I was so limited by what the people in my life wanted me to be, including my parents. My relationship with my parents actually got better once I moved away because it allowed for some distance, and through distance I think they were able to appreciate the changes that I was making as a human being. I think pronouns are one of those weird things where I don’t use my own. Sometimes I misgender myself because I never have to refer to myself as she/her in third person. But it’s something that requires people around me to use. And sometimes that feels frustrating, that this change that I’m trying to embody requires other people to hold and acknowledge and use. So, reinvention ultimately is dependent on other people. And I think, conversely, the exciting thing about it is that when people do come along for the ride, when people do embrace your changes, it can awaken different things in them as well. It can change their own perspectives on their own ideas of self—whether that’s about their gender, about their sexuality, about their own feelings about adulthood. The beauty of change is that once you accept and embrace someone else’s change, it can actually invoke growth in you.

Speaking of growth, I was taken by your statement that some “friendships need to die.” You also write about friendship breakups in relation to your divorce in 2016, which you didn’t consider a breakup but the end of a certain phase in your relationship. You still name your former wife, Shemeena Shraya, as your inspiration and thank her in all of your books. Can you elaborate on the generative power of such a friendship?

Sometimes I have found that long-term friendships are the hardest friendships to evolve in. We are really attached to people being a certain way in our lives. We get comfortable with each other, we want our friends to stay consistent, we want our friends to reflect back what we know, and that has made it really difficult for me to grow [as a person]. The central question I am grappling with is, how do you grow in long-term relationships? I look at my relationship with Shemeena and I hold it as a really great example of a relationship that has evolved and grown in such wonderful ways. It has been a long and, at times, painful and challenging journey, but both of us have always wanted to keep each other in our lives. That [desire] has always been at the center of the motivation to grow together.

I think queer people in general have done a great job reinventing the breakup. What Shemeena and I have done is actually very queer. I love her today more than I loved her when I met her 20 years ago. I think there’s something very queer about our evolution. I feel like I wouldn’t be who I am without her in my life. And, if you have supportive people in your life, your evolution can be transcendent.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra