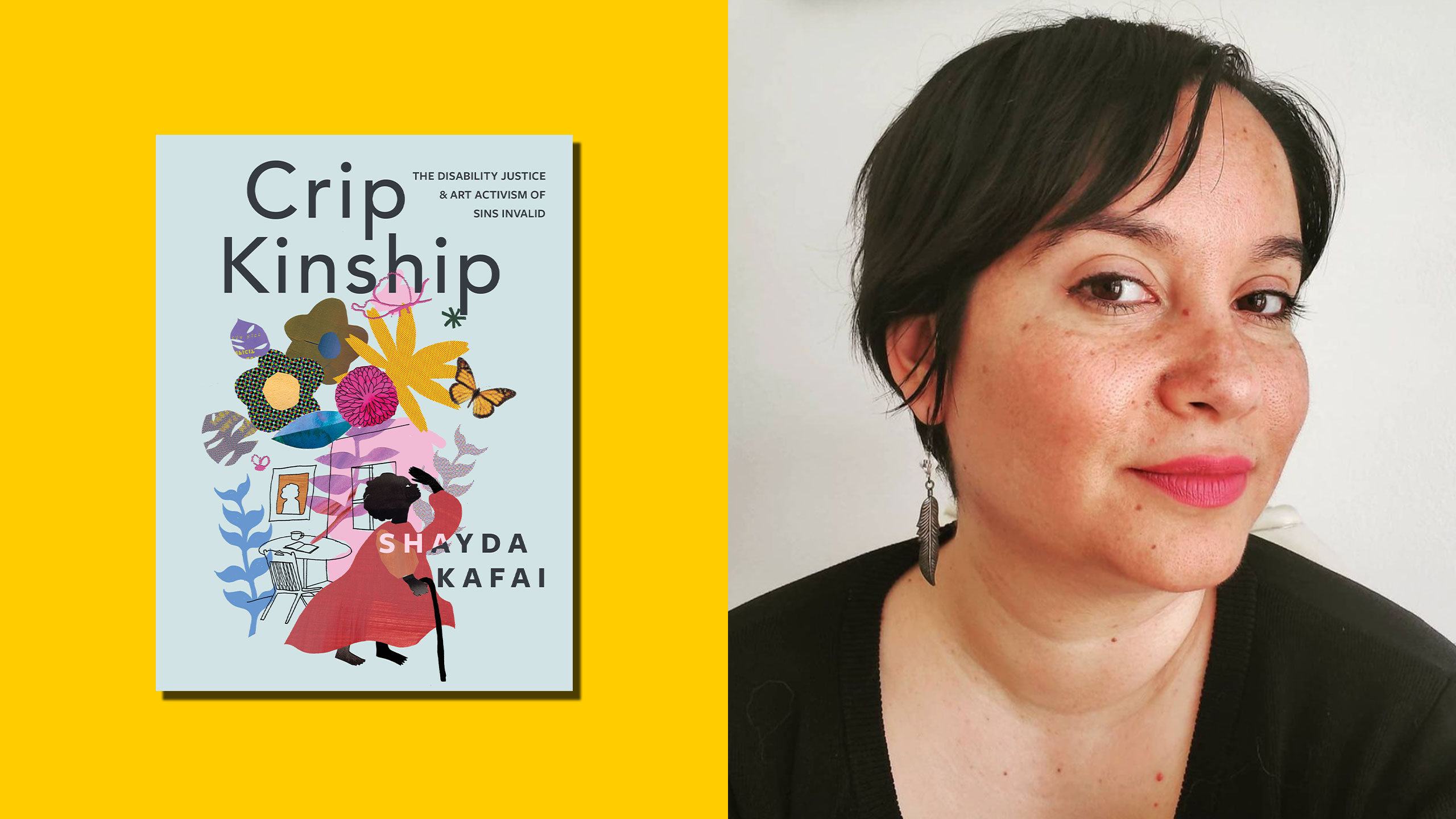

Since it hit in 2020, the pandemic has been considered by the disability community to be a mass disabling event, in which disabled lives were publicly declared as disposable, collateral damage in the name of saving the economy. In this context, Shayda Kafai’s new book, Crip Kinship, feels especially revolutionary. The book chronicles the formation and evolution of Sins Invalid, a collective of racialized and queer disabled performers who first came together as a performance project before going on to spearhead the disability justice movement in the San Francisco Bay Area and beyond; each chapter of the book is rooted in one of the 10 principles of disability justice on which the collective is founded.

Sins Invalid was formed when Patty Berne, Leroy F. Moore, Todd Herman and Amanda Cosler collaborated to form a performance arts space that was comprehensively accessible, not just to the audience but also to performers. Embraced by the community, they continued their project and developed primers on the principles and practices of disability justice.

Kafai’s look back on their work comes at a crucial time. “When I think about the current moment, it appears that ableism is doing better than ever,” warns founding member Berne in the forward. “As capitalism continues to define work, ableism becomes more and more entrenched in every generation.”

Crip Kinship was published in Canada in November, and will hit shelves in the U.S. on Dec 7. Ahead of the book’s American release, I got to sit down (virtually) with Kafai to talk about disability justice, crip culture and why we need to be centring queer, disabled, racialized bodyminds (a term that acknowledges how our bodies and minds can’t be separated) .

Can you tell us a little bit more about your introduction to disability justice and why you think it’s an important framework? How is it different from “disability rights”?

It started with me unlearning my own internalized ableism and sanism in undergrad. Finding community and talking to other amazing disabled folks helped me see what disability pride was. I learned about disability justice through the work of Sins Invalid in 2010. I was preparing to start work on my dissertation and I knew that I wanted to centre my community in my work. That’s when a friend introduced me to the collective. If disability studies, as a discipline, was not as white-centric (as disability studies scholar Christopher Bell alerted), then I can’t help but think that I would have more quickly arrived to QTBIPOC disability history, organizing and theory-making.

[The disability rights movement’s] focus on disability (particularly physical disabilities), whiteness, masculinity and legislation are very distinct from disability justice’s focus on intersectionality and the politicization of disability. Created by disabled folks of colour—who are also queer, gender nonconforming and transgender—disability justice acknowledges the intersecting oppressions that impact disabled folks. Racism, colonialism, white supremacy, classism, cis-heteropatriarchy—all of these systemic forms of oppression impact disabled folks, and disability justice reminds us that these too must be a part of the conversation.

I feel like it’s so necessary for me to be very clear and say that I wouldn’t be here in conversation with you today were it not for the labour and organizing folks from the mainstream disability rights movement. Yet, because of the issues around whiteness and heteronormativity, it took me that long to arrive at disability justice. Disability justice is important for two main reasons: one, that it centres collective access and liberation for all our bodyminds. Two, it is the first space I’ve been in where I’ve learned that I can express my needs without shame.

You mentioned it took you a long time to hear about Sins Invalid during your academic career. The group has been around for so long—why is it that more mainstream movements don’t know about their work?

Sins Invalid was first formed in 2005 by the amazing Patty Berne, Mia Mingus and our now ancestor Stacey Milbern. They were later joined by Leeroy F. Moore Jr. and trans disabled activists like Eli Clare and Sebastian Margaret. The community just kept growing and growing.

But the disability justice movement didn’t start with them. They name folks like Harriet Tubman and Frida Kahlo as origin points; part of the goal is to unearth, uncover and amplify the experiences of disabled folks of colour, folks whose names have been distanced from disability in our collective memory. I learned about how the Black Panthers supported the mainstream disability rights movement, and there was cross-movement building work there. Disability justice was the first time I learned about folks like Bradley Lomax and Johnnie Lacy, who are Black disabled activists who were a part of the mainstream disability rights movement.

The reason disability justice feels so new is because we are living in a non-disabled supremacy. The wisdom and the activism and the knowledge production of disabled folks is still incredibly marginalized and limited. Disability justice is also being co-opted by white scholars, white disabled folks. If the dominant discourse says that the knowledge of disabled folks is insignificant, then we’re not going to hear this magic, this wisdom, outside of the community, even though the work is being done by disabled, queer, gender nonconforming, trans folks of colour.

In the forward of Crip Kinship, Patty Berne speaks to an increase of ableism situated in capitalism, especially during the mass disabling event that is the pandemic. How do you see that playing out around you?

I’ve heard people say it’s time for us to get back to “normal,” and I consider that as one of the most ableist affronts. I think there are so many gifts from disability justice and the disability community—like principles of wholeness and sustainability, like mutual aid—that non-disabled community has been invited to exercise and engage with in the past couple years. As an educator and as a person living in the world, I want us to continue in slowness. I want us to centre our bodymind needs and engage with disability justice, not just as this beautiful framework, but as a practice.

What would a “culture of slowness” look like to you?

It would mean embracing disability justice and the idea of sustainability. That involves honouring our bodymind needs without shame, and being able to ask and communicate our needs as a political act. The work of antiracist, anticapitalist activist Tricia Hersey [creator of The Nap Ministry] is a great example. She says that naps can be a form of antiracist work and anticapitalist work because they are pushing back against this mandate of capitalism that we have to earn rest. Hersey is saying no, we deserve rest. I’m thinking about the racialized sleep gap and how folks of colour sleep less because they work more.

It would also mean embracing love. I think of bell hooks and her love ethic and how we really need to centre love for ourselves and love for community if we want to get free. And I see rest as this extension of love for self and love for community. Because if we’re centring rest for ourselves and for others, then we can really embrace our needs and those of community and kin.

In Crip Kinship, you speak to a lot of activists who are foundational to organizing the disability justice movement as we know it. What was it like to be in conversation with these activists and share in that knowledge?

It was fucking humbling that I could build connectivity with community living all over the U.S. and Canada. It was also humbling having really tender conversations [virtually] with Patty. There was a moment, for example, where we were talking and Patty’s assistant was creating these beautiful buns out of the curls on their head. Patty was drinking boba on screen, and so I felt empowered to pause the interview and say, “Hey, I need a food break too.”

The creation of the book was really dictated by the stories gleaned from the activists I interviewed. Because of the kinship, I very much felt in my moments of most profound self doubt of writing this [that] I was being held, like everybody was behind me in the room. So it was a very lovely experience.

You mentioned that the book took years to create. Can you tell me a little bit about the seed of Crip Kinship and how it grew into what was eventually published?

I first learned about Sins Invalid in 2010. I decided I was going to write about Sins Invalid in my PhD dissertation. It was completely different then than what the book became, which I think is actually lovely. In 2016, after reading a lot about very tangible, violent forms of crip erasure in the news, I realized that I was in desperate need of not just crip wisdom, but evidence that we exist and that our bodyminds are worthy of existing. I really wanted this to be a book for everyone, so it was important to cut the theoretical frameworks out that I needed for that degree. I really wanted the stories to guide the construction of the book.

You’ve spoken before about the erotic as pleasure-centred rather than sexual-based on works like adrienne maree brown’s Pleasure Activism. Can you describe what that means to you?

adrienne maree brown said that we need to align our pleasures with our values. I read Pleasure Activism first, and then I read the second edition of the disability justice primer that Sins Invalid put out, which also discussed the intersection of disability, erotics and sexuality. I was very much curious about how disability justice politicized sexuality. I was also thinking a lot about beauty and pleasure, mainly because it’s been so distanced from disabled folks of colour, disabled queer folks.

And because it’s so distant, it’s an incredibly radical, transformative act to say that we too are deserving of pleasure. The focus on pleasure is important for me and for Sins Invalid because it holds space for expanding what sex means and what the joy of that means.

It’s really queering the idea that pleasure—and sex as an extension—looks a certain way. And it’s holding space for all folks, including ace folks. And it’s something that is not regulated by the mandates of ableism and sizeism and racism in the same ways that our contemporary understandings of sex and beauty are.

I also want to take a second to ask about your use of the term “crip,” and specifically how you’re using it in terms of cripping sexuality and beauty.

“Crip” is an activist term, so it has similar lineages to “queer” in the sense that it was a term that had derogatory roots, but was reclaimed and reappropriated by community. It’s short for cripple, and the first time I heard disabled folks using the word crip was through the work of Sins Invalid and other San Francisco Bay Area activists. It’s a rebellious identity. It’s an identity of pride.

As an identity term, I think crip has a lot of potential as a verb. The word queer is a verb, right? It troubles, it expands; it renders messy all the norms that we consider in terms of pleasure, sex, beauty. And so one of the things Patty was sharing in an interview was that there is this idea that everybody has to mimic non-disabled sex, non-disabled pleasure, in order to have access to this thing we’re calling sex and pleasure. But if we’re cripping these two spaces then we’re literally rendering them messy and troubling, and challenging them. And, wow, such a huge universe then opens up if we have capacity to do that and if we imagine that as a way to move forward.

When reading Crip Kinship I felt—and this is something that Alice Wong speaks about—that storytelling is an act of love. This work does really feel like it comes from a place of love. Was that really intentional for you when you were writing it?

In the introduction, I frame [the book] as a love letter—both to folks that are searching for lineage and for their histories, and a love letter for myself, who was looking for community. It’s also a love letter offering our genealogy to folks that are in the movement.

There’s a section on care and compassionate reading in the introduction and the end [invites] the reader to write the next book on disability justice, and the next book and the next, and so from the way it was framed in the beginning to the end, yeah, this was most certainly intentionally a gesture of love.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra