For the better part of the last three decades, Rick Mercer has delighted audiences from coast to coast with his signature blend of comedy and political satire. But at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, Mercer, who decided to step away from television after 15 seasons of hosting his eponymous comedy series, was shocked at how completely useless he felt in the midst of a global emergency.

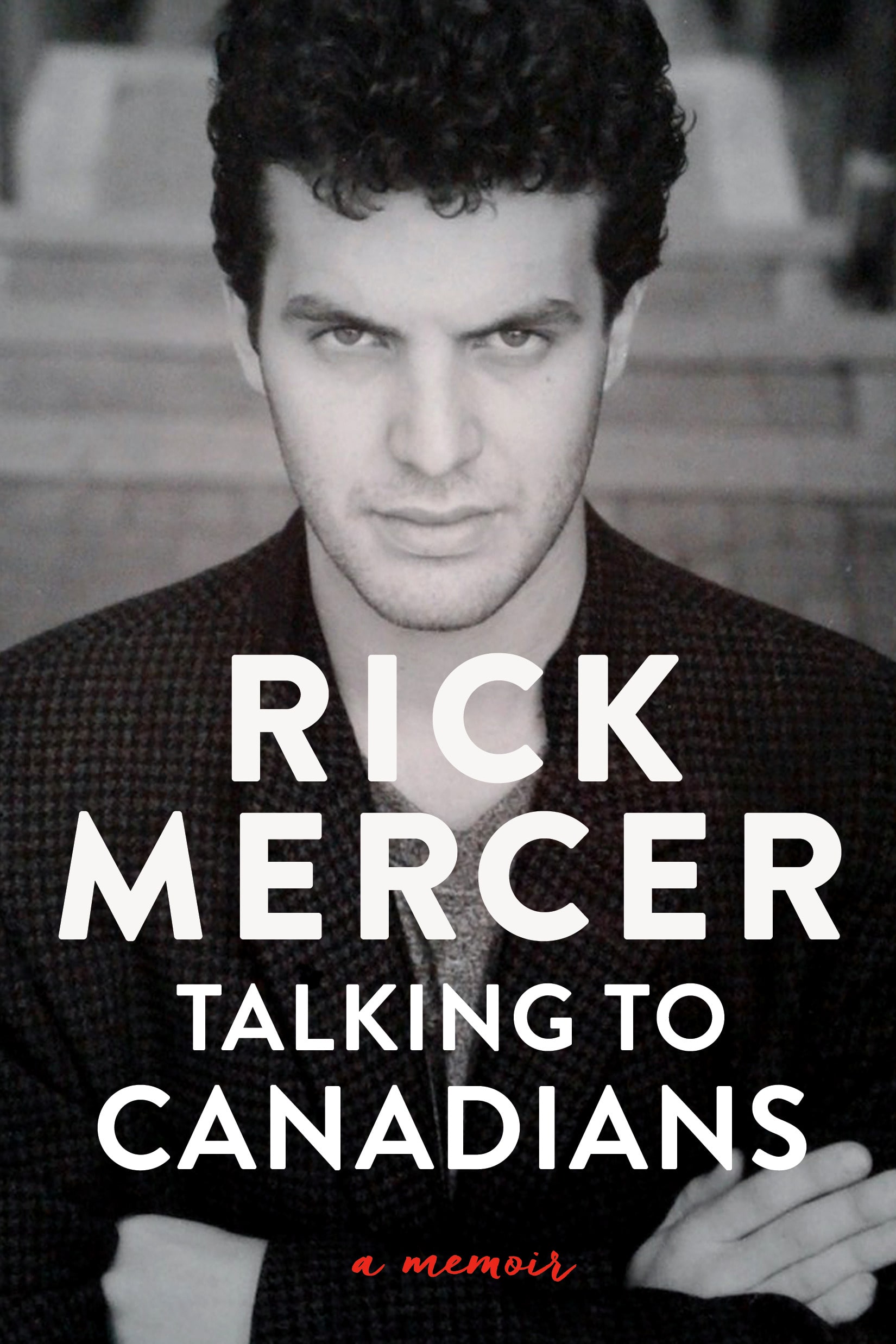

After years of shining a light on people from all walks of life in his TV shows, the 52-year-old comedian decided to turn the spotlight on himself. Told in riveting, anecdotal style, his memoir, Talking to Canadians, published last November, chronicles his rise from unpromising schoolboy in Newfoundland to the heights of Canadian television. In it, Mercer pulls back the curtain on the defining moments of his career—which include his acclaimed one-man show Show Me the Button: I’ll Push It (or Charles Lynch Might Die) (1990) and his work on This Hour Has 22 Minutes (1993-2001) and Made in Canada (1998-2003)—as well as his long-standing relationship with the producer Gerald Lunz, whom he calls his “partner in life and in business.”

In a recent phone interview, Mercer spoke candidly with Xtra about his relationship with Lunz, the delicate balance of working with (and poking fun at) politicians and how he thinks the world will reflect on this era of sociopolitical change.

When did your own education and interest in politics begin, and when did you decide to combine that with comedy and satire?

Politics has always been of interest to me. My father and I talked about it a lot around the kitchen table. Newfoundland had a very colourful political scene. I had a godfather [Hugh Shea] who was very good to me, who was a very colourful character, who was involved in politics in Newfoundland, and he was fairly eccentric. He was elected as a Conservative during a very contentious election that resulted in a tie between the Conservatives and the Liberals, and he crossed the floor that night. He would go on to run for the leadership of the Liberals and the Tories. He was just always great to me. He was one of those adults who would have serious political conversations with a 10-year-old, and I always appreciated that.

It was just my “baseball.” Other kids were into baseball, I wasn’t. I liked provincial politics—I don’t know why, but that’s just the way it was. When I started doing comedy, I didn’t originally think that there would be much politics involved. But when I did my first one-man show, I really took a deep dive and did a show about the Meech Lake Accord, which was a Canadian constitutional crisis. You can’t think of a more boring subject—it’s hard to believe that anyone would decide to write a comedy show about it, but I did and the public really had an appetite for it. The show became a game changer for me, because I ended up touring the country, and a light went off and I saw the way forward. So, from then on, politics and comedy were always meshed.

I really loved the story of how you first met Gerald, who originally wanted to fire you from your job as a theatre technician for your friend Cathy Jones’ play. How would you say you have grown not only personally but also professionally with him since that fateful first meeting?

Credit: Courtesy of Doubleday Canada

Well, I was 18 years old when he wanted me fired, and rightly so. [Laughs.] I was hired to do a job that I was woefully under-qualified to do and one that was very important and required real skills—none of which I had. Plus, I was lazy. It was why I was such a poor student; it was why I never belonged to anything. It was only when I discovered the theatre and comedy that I developed a work ethic.

I wouldn’t suggest to everyone that you work with your partner in business or in the arts—it doesn’t always work out (look at Sid and Nancy, for example). But there are those certain creative relationships that just work. Because we have a personal relationship, I had, in my corner, an expert in artist management and the greatest producer in the country. He wasn’t in it for 15 percent or 20 percent. He was in it for the long haul. Because we were in a relationship together, that obviously made all the difference in the world. I can’t tell you how many people in show business have said to me over the years: “I wish I had a Gerald!” It’s a different level of commitment to one another.

You also touch on your own coming-out journey, and the trepidation that you felt as a closeted young man, even if you were part of a liberal arts community in a pretty progressive part of the country. When did you first realize that you felt different from others?

I was one of those people who always knew I was gay. Some people say, “I realized I was gay in the first year of university.” I’m like, “Really? I think I figured it out at five.” But I just put it on the back burner—I’m not suggesting that people do that, but it was a bit of a different time. There was no gay-straight alliance in my high school, but there was a drama club, which is why I went there.

The important thing to me was, once I came out, I was out by all standards that anyone can be out—meaning my family, friends, co-workers and people on the street knew I was gay. But I certainly didn’t go out of my way in the early years to make it part of my public persona. I developed a public persona because of the comedy show and because I was on This Hour Has 22 Minutes. The only thing I promised myself was that if anyone asked me about being gay, I would never deny it, certainly. But the question never came, whether it was because of politeness or because of the times—you just didn’t ask a question like that—and then eventually I decided that it was important to be public about being gay because of the issue of representation.

I remember the day I heard that the weatherman was gay on CBC in St. Johns, when I was 15 years old. I thought, “Wow, Karl Wells is gay? And he lives with a man, in a house, in the suburbs? This is insane!” That was a real game changer for me. I realized that I just had that same responsibility to be a Karl Wells to some gay kid in Saskatoon who might go, “Oh, my parents are watching a TV show. Hey, he’s gay, mom! What do you think of that?” [Laughs.]

Your Harvey’s run with Prime Minister Jean Chrétien in 2007 deserves to be its own Heritage Minute. You’ve been fortunate enough to interact with so many leaders over the years in what you describe as a “mutually parasitic relationship.” How were you able to walk the line between getting and maintaining that access while also continuing to poke fun at them?

Well, it’s a very fine line. And in fact, it’s something I stopped doing. The Mercer Report intentionally didn’t do that. Yeah, sure, prime ministers were on the show, and Bob Rae was on the show when he was running for the leadership in the Liberal Party, and Jagmeet Singh was on the show when there was a lot of talk that he might leave provincial politics and run for the federal leadership of the NDP. But months and months and months would go by before we had a political figure. I was more likely to have a farmer or a fisherman or a nurse on the show than the political figure.

That was in part because I knew, if it was happening all the time, it’s very hard to maintain any kind of balance, because you start to develop a personal relationship with them, and I didn’t even want a personal relationship with any of those people. Once you’re friends, you’re no longer an independent observer, that’s for sure. It’s very easy to like these people because they’re very personable. The vast majority of them are very personable, because if they weren’t, they wouldn’t have gotten elected. At the end of the day, it’s all about knocking on doors in most markets and you have to sell people. They’re generally the type of people whom you would enjoy having a chat with, so you have to be very careful about that.

You write glowingly about the Christmas specials that you were able to do for Canadian soldiers. But is there a piece that you are most proud of?

When it looked like the Alliance, which is now the Canadian Conservative Party, were really making inroads in Ontario and they had this notion of a citizen-initiated referendum, I knew exactly what it was. It was all about gay marriage, it was all about the death penalty and it was all about limiting access to abortion, and no one was talking about it because it didn’t seem like a sexy issue. To me, it seemed like the most pressing issue of the election, but it just wasn’t getting any attention.

We came up with a way to illustrate how easy it would be to get 350,000 signatures and initiate a citizen referendum on an issue like gay marriage, and we did it by launching a petition to force Stockwell Day, who was the leader of the party, to change his name to Doris, which I loved because it was just funny on its own. I knew that as a person who was incredibly active in most of his career to limiting gay rights and any progression of the gay community, it would drive him to complete distraction, that people for the rest of his life would call him Doris. I was particularly proud of that one, I got to say, if I had to look back. [Laughs.]

I can’t speak with you without bringing up Talking to Americans, because my Grade 10 history teacher actually introduced me to your work with that segment. Was there ever a time when you felt you had pushed the envelope too far when it came to your lies about Canadians?

Every time I went down I thought I was pushing it too far, because as the piece progressed, I had to get increasingly absurd. Once you can get people to say, “Congratulations, Canada, on legalizing insulin” or “50 miles of paved road” or you convince people that Canadians are going to drill into the heads of the presidents at Mount Rushmore to extract plutonium from their skulls, it’s tough to figure out, “Okay, what am I going to do to top this?” And every single time, I thought, “Oh, I’m just going to come up with a question that’s going to get me a punch to the head.” But it never happened. It never ceased to amaze me, their lack of knowledge of Canada, but it was a great, great gig.

I was on a hit comedy show, and then out of nowhere, I had a segment on that show that people were demanding week-after-week. And in order to do that, I would fly to a great American city—San Francisco, New Orleans, Chicago, New York. I would work for five or six hours, we would pull this thing off, and then we would go to a ball game or we’d go tour a museum, and then go to dinner and come home. It was literally the best thing that has ever happened to me. [Laughs.] It was wild, and then it culminated with this special, which, to this day, at least twice a week, someone will stop me on the street and talk to me about. And quite often, it’s someone like you who watched it when they were kids in school, which I love.

Since you left TV, the political divide that exists between people in the Western world seems to be getting bigger and bigger. How do you think we will look back at this era of social and political change?

I hope that there’s some sort of light at the end of the tunnel, because there’s just so many hurt feelings and so much anguish and so much anger. And I’m not saying that people don’t have reasons to feel hurt or afraid or any of those things, but it just seems to be unboxed right now, and it doesn’t seem to be sustainable for the long run. All I know is, in the last four years, I’ve never seen anything so strange in my life. It’s gotten to the point now if I wake up tomorrow morning and flick on the TV and they say, “Oh, alien spaceships are now hovering over nine major cities in the world!” I would think, “Well, of course!” [Laughs.]

“Everything happening in the States in the last five years would have been impossible to comprehend 10 years ago.”

Everything happening in the States in the last five years would have been impossible to comprehend 10 years ago. And throw a pandemic on top of everything else and the level of social upheaval that has been happening? It’s completely bonkers. Every single time you turn on the news when it comes to the climate, it’s like the start of every disaster movie, so it’s a lot to take in!

What’s next for you?

I’m going to go out and do another stand-up tour with Just for Laughs, because I really enjoyed that and stand-up has a lot to teach me. Maybe it doesn’t make a lot of sense on paper to be doing that at this point in my life, but that’s what I want to do, so I’m going to do that.

Everything I’ve written other than my sitcom, Made in Canada, has been about standalone items that are three or four minutes or 90 seconds, so it was a real learning curve to write [Talking to Canadians], something this long-form, and just work in the shed on a document that no one read for an entire year. It was completely different, but I can’t say I didn’t like it, so maybe I’ll tackle something else like that, but it won’t be part two—at least not right away.

The book ends with the start of the Rick Mercer Report, so will there be a second book about your experiences during that show?

Oh, for sure, and that would be a very different book. [Talking to Canadians] is an origin story, and it’s about the ’80s and so many different things, and I’m really happy with the fun stories. A book about 15 years of being on the road with the Mercer Report would be very different because this book doesn’t have run-ins with famous people, but the Mercer Report has loads of that. So it would just be a different project, but one that I look forward to doing someday, because I love telling those stories.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra