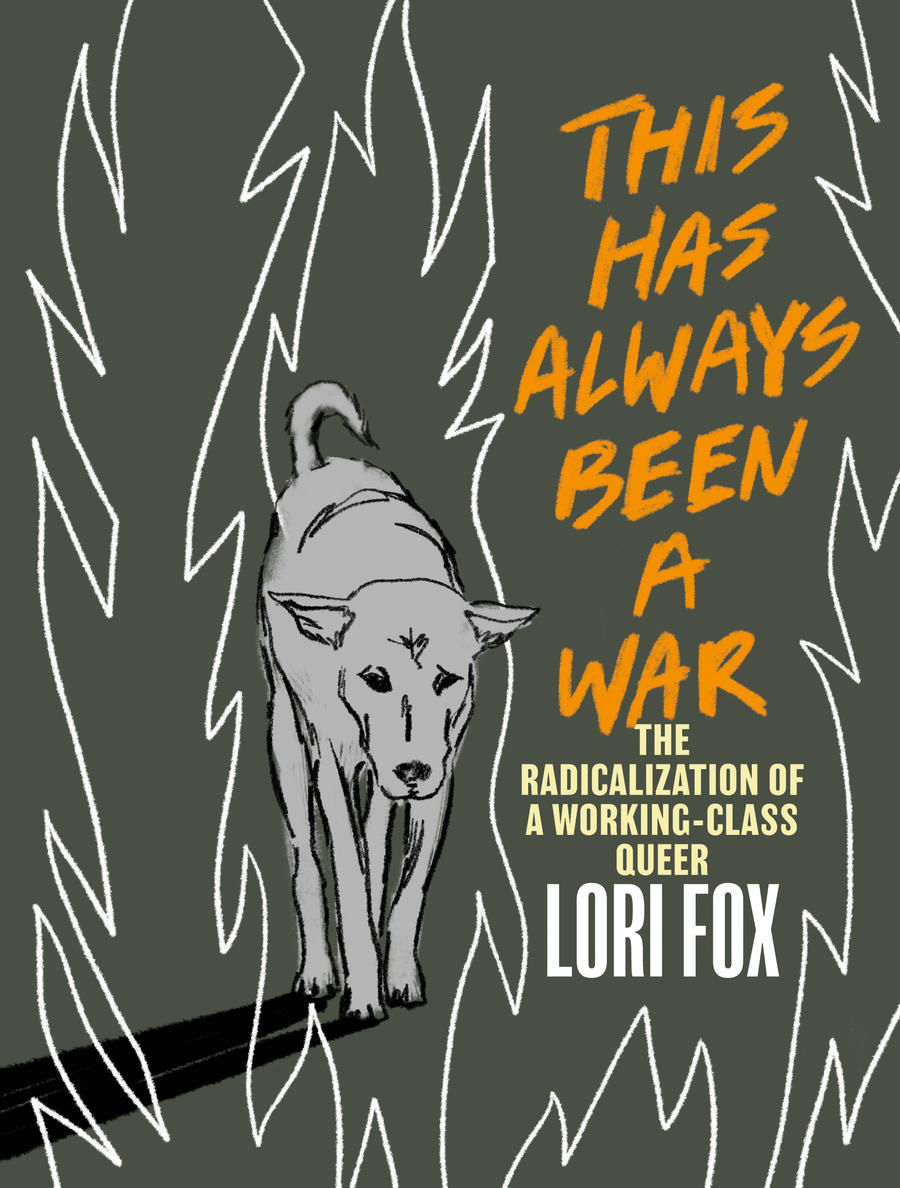

In the essay collection This Has Always Been a War, to be published next week by Arsenal Pulp Press, Laurence Fox takes on the capitalist patriarchy, making the personal political and the political personal. Fox, a queer non-binary writer and journalist living in Whitehorse, Yukon, mixes personal experiences, social and cultural criticism and a polemic style in an engaging prose—they sound like the best friend you met at a late-night party, the friend you never agree with until you do. In this excerpt from the book, Fox writes about current trends in feminist dystopian fiction and how queer and non-binary people are left out of the picture.

There is nothing more pleasing to me, more vindicating, more enrapturing, more sublime, than a woman who is absolutely fucking furious.

I love it when femmes lose their shit in bars, spitting insults and slapping unwanted hands away and throwing drinks in people’s faces. I love it when butches throw that hard-jawed, stony stare at some guy who calls them dyke, that look that means fuck you, breeder. I love the trans women calling out TERFs like J.K. Rowling, fanning the flames of the pyres on which the Harry Potter books burn, the literal smoking ruins of cisheteronormative mediocrity. If I could, I’d feed the wood stove in my cabin exclusively with second-hand copies of The Deathly Hallows, Dave Chappelle headshots, and yard sale Margaret Atwood novels—the only way to draw any warmth from the latter’s lifeless prose would be to burn it.

All our lives, we—and I say here “we,” because although my gender is androgynous, for most of my life thus far I have been treated as a woman and probably always will be by certain people—are discouraged from anger. Women are supposed to be “nurturers” and “caregivers,” which is man-speak for “physically and emotionally available doormat who never says no and always puts other people first, men especially.” An angry woman is a “bitch,” a “cunt,” a “hysteric”—but even if that’s true, so what? What’s wrong with being a bitch when being a bitch is called for? There’s so much suppression, so much malice, so much disdain and dismissiveness for female rage that our every justifiably angry word and wrathful act is an act of defiance and rebellion.

In some ways, the social censure of women’s anger seems to be loosening; the #MeToo movement has brought toxic masculinity and male privilege to the fore, with public accusations of sexual assault, misogyny and misconduct against big-name men like Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein, actor Bill Cosby and literary biographer Blake Bailey. And yet, even as women push forward, men push back, and push back hard. Abortion rights rolled back, vicious attacks on trans women, court cases against abusers lost or overturned, not to mention the COVID-19 pandemic, which has impacted women’s employment, earnings and careers disproportionately to their male counterparts. The misogynist culture of incels—increasingly and inextricably tied to racist, fascist, queerphobic movements and political ideology, as portrayed in Talia Lavin’s 2020 work, Culture Warlords—is becoming alarmingly mainstream and violent.

As Louise Erdrich says in her 2017 novel, Future Home of the Living God, men have become “militantly insecure.”

Basically, shit’s all fucked up and getting worse all the time.

With the way things are, it’s not surprising there has been a huge surge in dystopian literature, largely written by women, for women, about women’s issues in the last decade. As publishing reporter Alexandra Alter wrote in The New York Times, “This new canon of feminist dystopian literature … reflects a growing preoccupation among writers with the tenuous status of women’s rights, and the ambient fear that progress toward equality between the sexes has stalled or may be reversed.”

“I began to devour feminist dystopian novels, one after the other. I’ve always turned to books when I feel alone, and I was feeling very, very, very alone at that time in my life.”

I love dystopian novels. A good dystopian novel is a translation; something large and frightening and abstract is made personal. Dystopian fiction is both exposure therapy and catharsis, and in early 2018, healing from a recent sexual assault, frustrated and exhausted by the apathy and impotence of both the law and the men who make and enforce it, and just generally weary of the day-to-day misogyny having a pair of tits gets a person, I began to devour feminist dystopian novels, one after the other. I’ve always turned to books when I feel alone, and I was feeling very, very, very alone at that time in my life. It was vindicating to hear voices as angry, as frightened, as disturbed by the world as my own.

I started off with Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale—a natural choice, as in recent years Atwood has come to be recognized as the founder of the modern genre. In it, the once-United States becomes the totalitarian regime Gilead following a coup by right-wing Christian extremists dedicated to controlling women’s bodies in the wake of a fertility crisis. Later, I read The Testaments, Atwood’s follow-up novel in which a full generation has passed and grown up in Gilead, which is beginning to show cracks in its control, and The Power by Atwood’s protégé, Naomi Alderman, in which all the women in the world suddenly evolve the power to blast electricity from their hands, like electric eels, upending the traditional power balance between the genders.

I chewed through Leni Zumas’ Red Clocks, in which new draconian laws on abortion, IVF and adoption alter the lives of three women; and Helen Sedgwick’s The Growing Season, set in a parallel world where technology has “freed” women from physical pregnancy in the name of equality, but the company that controls it is keeping a dark secret from its users. Later, I read Erdrich’s aforementioned work, Future Home of the Living God, written as a series of letters from a pregnant woman to her unborn child in a near future in which creatures—humans included—are evolving backward, birthing long-extinct versions of their species ancestors, causing the government to begin capturing and imprisoning pregnant women.

More and more and more novels. I read and read and read. As I did, a pattern started to emerge, one which, as a queer person, as a working-class person, as a non-binary person, as a feminist, began to disturb me.

I felt I was on the trail of something, so I read some more.

In Sophie Mackintosh’s The Water Cure, a family sequesters themselves from a world torn apart by a mysterious disease carried by men that may or may not be imaginary, but which sickens women nonetheless, causing the women of the family to subject themselves to cruel and bizarre “purification” rituals levied and governed over by their all-powerful father, King. Later, I read Mackintosh’s second novel, Blue Ticket, in which women are either allowed or prohibited by the state to have children—with dire consequences for anyone who attempts to change their lot.

“One hundred hours of words in which queer people are almost entirely absent.”

I read Christina Dalcher’s Vox, in which a far-right Christian American government has forbidden women from working, reading or writing and fitted them with shock-collar devices to enforce a limit of a hundred spoken words a day.

On a road trip to Keno, Yukon, I chewed through Jennie Melamed’s debut novel, Gather the Daughters, in which an isolated island community, having fled a disaster on the mainland generations ago, forces girls to marry the year they begin menstruation, and men are granted complete authority over their households—even though the world beyond the island may not be all that they have been told.

I read ten books in all, most of them written in the last five years. I primarily consume novels as audiobooks, so I know exactly how much time it took: 100 hours of words.

One hundred hours of words in which queer people are almost entirely absent.

One hundred hours of nightmarish scenarios of incredible danger for women and female bodies in which no one bothers to explain—to think about, even—what happens to us.

One hundred hours of imagined futures in which we, apparently, do not exist—or perhaps, simply do not matter.

If this is feminist dystopian fiction, for whom is the “feminism” it depicts?

How can you have feminism without queer women and non-binary people?

Where the fuck are we in your dystopia?

To be clear, it’s not that I would expect all of these works to include a queer character, or even to mention queerness as a thing that exists in the world. Not every book has to be everything to every person. I’m the whale shark of readers, just swimming around out there in a blue-green sea of books, opening my mouth and letting them drift on in, and I love lots of books that are written by straight people about straight lives without even the whisper of queerness about them. These novels, however, are special in that they are designed—and marketed—as inherently feminist, i.e., about the rights and issues of women generally.

Only four of these ten novels, however, mention queer people of any gender, even in passing.

Only three feature lesbian characters, and of those, only one shows those women actually engaging in same-sex romance and sexuality.

None feature non-binary or openly trans women at all, in any context, at any time.

Once is an accident, twice is coincidence, three times is science, and this is a motherfucking phenomenon, baby.

What the fuck is going on here?

So, what are these books, these supposedly feminist 1984s and Brave New Worlds, about?

Universally, every single one of these books is about the way men, individually or as a gender, seek to control, confine and subjugate women and their bodies at a personal, social or government level—sometimes all three. Women in these (mostly) imagined worlds are held captive, sometimes against their will, as in Vox, The Handmaid’s Tale and Future Home of the Living God, sometimes without their even knowing that they are prisoners, as in Gather the Daughters, The Water Cure and Blue Ticket. Across the board, there is an inherent, innate fear of both religion and the state, as one or the other (and often, both) reach out to force women into submission. It is a fear which is well founded and with myriad historical examples, from the present Christian right’s attacks on women’s bodies through limiting access to birth control and abortion in the United States, to the biblical Ephesians 5:22: “Wives, submit yourselves to your own husbands as you do to the Lord.” The vast majority of these novels—eight out of ten—have pregnancy and children at the heart of their narrative: having babies or not having babies, getting abortions or not getting abortions, wanting children and not having them, having them and not wanting them.

Overall, these are novels in which women are afraid of men because men do bad things to women—dystopias rooted firmly in reality, because men, empowered by the holy trinity of capitalism (the state, the patriarchy and religion) do bad things to women (and non-binary people) all the fucking time.

For the purposes of this essay, for a novel to be counted as a work of feminist dystopian fiction, the story’s events and society must be fictional and focus on women (or assigned female at birth, AFAB) bodies as a whole. For example, I could have counted Miriam Toews’ Women Talking—in which the women of a Mennonite community debate whether or not they wish to remain after a handful of men in the community drug and rape several of them in their sleep, only for their leaders to admonish them into forgiving them, with no repercussions for the perpetrators—but I didn’t, because although it is both decidedly feminist and decidedly dystopian, the novel is based on real (if fictionalized) events and societies. Likewise, I could have included Ling Ma’s superb anti-capitalist novel Severance—in which a fungal infection turns people into hollowed-out zombies, and a young woman is held captive by a middle-aged man because he believes her child will be the start of a new world—but I chose to omit that as well, as the bodily oppression is happening to only one woman, not all women.

These works and, more broadly, the women who write them, as well as those who read them without a critical eye (in every single review I read of every single one of these books, none mentioned the absence of queer people in the narrative, nor the fitness of their representation in the scant instances they did appear), seem to quite mistakenly believe that the problems of cis-heterosexual women are exclusive to cisheterosexual women.

They are not.

As any dyke will tell you, being in a relationship with another woman does not preclude you from being objectified by some Kyle at the end of the bar who won’t quit staring at your tits.

As any enby [non-binary person] will tell you, presenting androgynously (or masc or femme of centre) does not preclude you from being sexually assaulted.

As any trans woman will tell you, being trans does not protect you from male violence.

That’s not simply my opinion, nor is it merely anecdotal—the stats bear it out. Bisexual and trans women (including bisexual trans women) experience significantly higher rates of sexual and intimate partner violence, with more barriers to access than cisheterosexual and even cis lesbian women. The numbers rise again for people of colour, especially Black bisexual women. For reasons that aren’t entirely clear (stigma is believed to play a role), bisexual and, in some cases, lesbian-identifying girls are more likely than their heterosexual peers to have an unwanted teen pregnancy in both Canada and the United States, and transgender youth are as likely to be involved in a pregnancy as their cis peers. The rates of same-sex couples raising children—pregnancy and child-rearing are an overwhelmingly common theme in these books—are rising dramatically. Almost half of all trans women report having been sexually assaulted at some point in their lives, and if they’ve done and/or do sex work, that number jumps to 72 percent.

Being a queer woman or trans or non-binary person doesn’t mean being immune from the problems of misogyny and patriarchy. It actually means dealing with all the socially ingrained misogyny all women deal with under the capitalist patriarchy, plus a whole bunch of other shit that comes with being queer and/or gender-nonconforming. Add in being a person of colour, or neurodivergent, or disabled or working class, and you’ve got yourself a pretty fucking potent cocktail of oppression—one that these gin-and-diet-tonic, middle-class, cishet white “feminists” probably couldn’t even pronounce to properly order, never mind choke down.

“Does that not sound like the life of someone who lives under the weight of misogyny and patriarchy?”

Personally, as a queer, non-binary person with a female-coded body who (very) occasionally sleeps with men, I’ve been sexually assaulted twice. I frequently get catcalled and shouted at—calls for sexual favours, questions about my gender when I walk home alone at night; even in my small community, I carry a knife, because I know men cannot be entirely trusted even at the best of times.

Does that not sound like the life of someone who lives under the weight of misogyny and patriarchy? And yet, not one of these books contains someone who looks like me, who exists as I exist; there’s not a single person in all ten of these so-called feminist novels who I could relate to.

Excluding queer women and non-binary people from these conversations, as they are excluded from these books, effectively erases and invalidates their experiences. It’s not as if I and people like me don’t fight and suffer alongside cis-heterosexual, even cis-bisexual women. We do; queer women and non-binary people have been leaders in the women’s rights movement since the days of suffragettes. It’s as if these novels are saying the part about you that matters most is whether or not you relate in a daily romantic, sexual way to men. Curious criterion for supposedly feminist novels.

To say the quiet part out loud, our exclusion from these “feminist” books says: you are not one of us.

Excerpted with permission from the book This Has Always Been a War by Lori Fox, published by Arsenal Pulp Press, 2022.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra