For two decades, one man had the last word on Kay Dick’s career. After the London-born author died in 2001 at age 86, journalist Michael De-la-Noy wrote an obituary for Dick that read more like a gossip column. He disparaged her as prioritizing “personal vendettas and romantic lesbian friendships” over writing books, catalogued her trail of lost friends in an unmistakably catty tone and claimed that her talent had been dissipated in “avenging totally imaginary wrongs.”

Yet between the 1940s and the 1970s, Dick was a luminary of the London literary scene. The first female director of an English publishing house, she worked on George Orwell’s Animal Farm and wrote seven well-received novels of her own. She was close friends with many of the best authors of her day—among them Olivia Manning, Stevie Smith, Ivy Compton-Burnett, Brigid Brophy—and was also openly bisexual, living with her partner Kathleen Farrell from 1940 to 1962. Her autobiographical novel The Shelf captures much of the everyday homophobia she experienced as an openly queer woman decades before any formal queer rights movement.

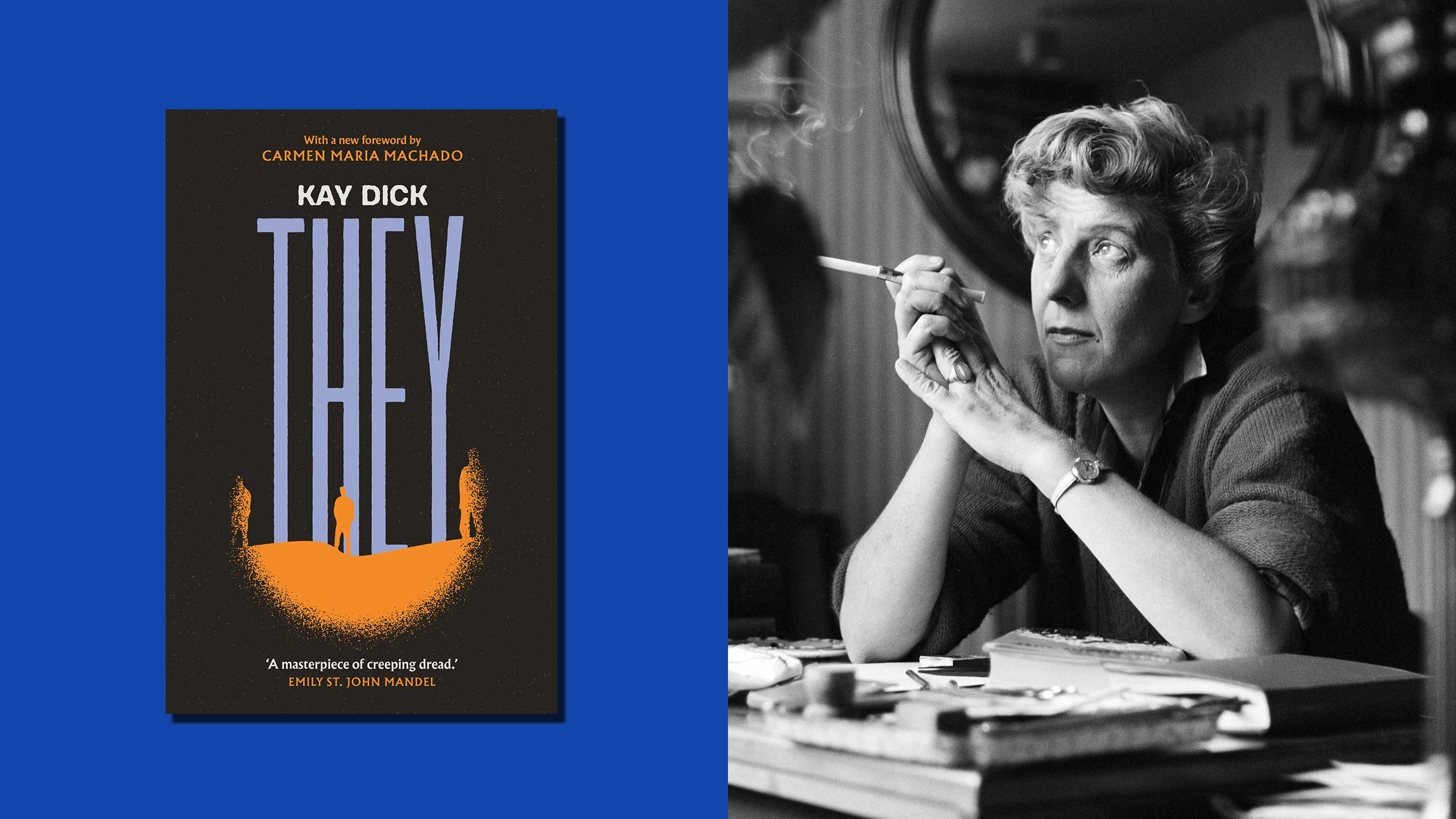

Despite Dick’s work being acclaimed and winning literary prizes in her lifetime, it never sold well, and she was in financial difficulties throughout her life; until this year, De-la-Noy’s damning obituary had been the last widely circulated word on her career. But Faber’s upcoming reissue of Dick’s book They, a strange and mesmerizing “sequence of unease” that won the South East Arts literature prize in 1977, marks a reevaluation of her legacy.

“Resistance consists of small acts of defiance and beauty.”

They is a slim, spare, quietly brutal novella (or a collection of linked short stories, depending on your perspective) that takes place in a Britain menaced by a faceless collective, the titular “they,” that seeks to prevent the expression of art, culture and identity. We see them indistinctly, through an oppressive haze of surveillance and fear, broken by flashes of extreme violence: a poet with her arm held over an open fire; a lobotomized woman staring into space. The protagonists, a cluster of artists on the Sussex coast, try to survive and furtively make art, but there is little sign of “their” control being challenged. Resistance consists of small acts of defiance and beauty.

Dystopian novels are tricky to pull off. How do you strike a balance between being ham-fistedly obvious and being so vague about the object of your anger that it becomes almost meaningless? “Metaphors are easily abused,” points out Carmen Maria Machado in her introduction to the new edition of They, “you have likely heard your ideological opposite invoke 1984 in their own defence, making (you are sure) the opposite point the author himself was making.” Anything from terrifying acts of state surveillance to the most basic civil rights protections can be denounced under the same moniker: “Orwell’s nightmare.” They is beautifully written and economical with its prose, but it’s also a striking example of a dystopia that manages to tackle this ongoing problem by being specific without being too overt.

In “The Visitants,” the narrator, a singleton, is visited by Lou and Jed, a couple who are part of the collective. Jed is violent towards Lou, while Lou is passive, watchful and admits a love for flowers, which Jed responds to by striking her. They practice a disturbing facsimile of sex, after which Jed pushes Lou away. In other chapters, there are similarly strange interactions with the collective: “they” leave a seaweed crucifix on a person’s doorstep; “they” practice a strange group routine in which they entrap people, who die of fear. You cannot hear them coming because “they” do not wear shoes.

“The book’s paranoia feels very queer: the collective is always watching you.”

There are marks of personal haunting here. The book’s “heroes” are mostly middle-aged, independent artists based in Sussex, the county where Dick died. They’s queer sensibility is consistently evident: the “dedicated single” status of some of the book’s characters, the collective’s harsh performances of conformity and misogynistic heterosexuality, the indistinct gender of the narrator. The explicit romances in They are straight ones, but the book’s paranoia feels very queer: the collective is always watching you, taking books off your shelves, punishing expression that goes “beyond the accepted limit.” “Non-conformity is an illness. We’re possible sources of contagion,” a character says, darkly. “We’re offered opportunities to—integrate.”

But They is compelling beyond directly queer readings. The book feels startlingly contemporary in how it depicts a hazy, omnipresent fascism, one that makes it hard to think, let alone understand. The idea of a world in which a hostile force with an incoherent and violent ideology has stealthily taken over the country, keeps people under constant surveillance, turns up at your door, eats your cake and considers strangling your dog, is far more prescient than I would wish.

They is an excellent depiction, at least, of what it is like to be a white, well-connected queer artist under conditions of fascism. The characters live in fear, but are also given certain leeways and licenses. There is a continuous sense that more violence is going on somewhere, elsewhere, but little sense of who it is happening to, or who is most likely to be holding the knife. The lack of explicit descriptions as to who is in the collective and why means that we can’t cleanly designate ourselves as “not them.” But the limited range of protagonists does impede our ability to gain a full sense of what They’s world is like for people more marginal than self-supporting Sussex intellectuals.

“It can feel like the protagonists are shielded from fascism purely by virtue of being artists.”

If there is one thing I would change about They, it is that this particular cluster of protagonists seems immune to becoming part of “them.” The collective’s strength is in their numbers, but we don’t see what it’s like to be lured in by them, only what it’s like to be surveilled and violently punished by them. Because its main characters are mostly independent artists, it’s easy to view this as a book where painters and poets are morally inviolable and are set upon by philistines who can’t appreciate a good Yeats verse. The book does subtly reject this polarity in some ways—a ringleader of the collective tells a musician character whose music was burned, “Pity about your music, I rather enjoyed it,” suggesting that the destruction of art is a deliberate oppressive tactic rather than coming from fear or ignorance. But without seeing anyone be “turned,” it can feel like the protagonists are shielded from fascism purely by virtue of being artists.

Nevertheless, the paralyzing atmosphere and strange, lovely interactions in They have stuck with me in the weeks since I first read the book. The book holds a blade to a nerve—not cutting, just pressing. Queer artists have been using apocalyptic and dystopian writing for a long time because it takes something all-consuming and elusive and makes it visible: the currents of bigotry, cruelty and disinterest that manifest in eerie silence, your losses of work and money, your persistent feeling that you are going mad. Whenever I talk and sense that people are not listening because I’m trans, I can feel that invisible hand around my throat. But I can’t ever confirm that it’s there. That’s the paranoia.

Dick writes paranoia masterfully, but De-la-Noy did her a great disservice by only characterizing her as a bitter, vengeful paranoiac. She was a colourful and spiky figure: a host of legendary dinner parties, a key figure in the introduction of the public lending right (so that authors receive royalties when their books are borrowed from public libraries) in the United Kingdom, an acclaimed study of the commedia dell’arte, a hot butch and (most likely) a bad friend. Almost none of her books are still in print.

Meanwhile, the prose of Dick’s partner Farrell, who was also a writer and also dismissed by De-la-Noy in his obituary of her, is currently only visible on a blog by a dedicated researcher of underread British women writers.

Like so much else in queer history, texts like They have remained mostly inaccessible, waiting for someone with enough luck, time and power to stumble upon them and bring them back into the public eye. In Dick’s case, Paris Review editor Lucy Scholes chose last year to profile They, while, coincidentally, literary agent and editor Becky Brown was intrigued by a copy of They she found in a charity shop—their interventions helped kickstart the reissue. It doesn’t often happen. This time it has. They is a troubled, troubling, excellent little book, out of print for over 40 years, and its overdue re-publication places Dick’s legacy firmly back in her own hands. May far more queer authors receive the same.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra