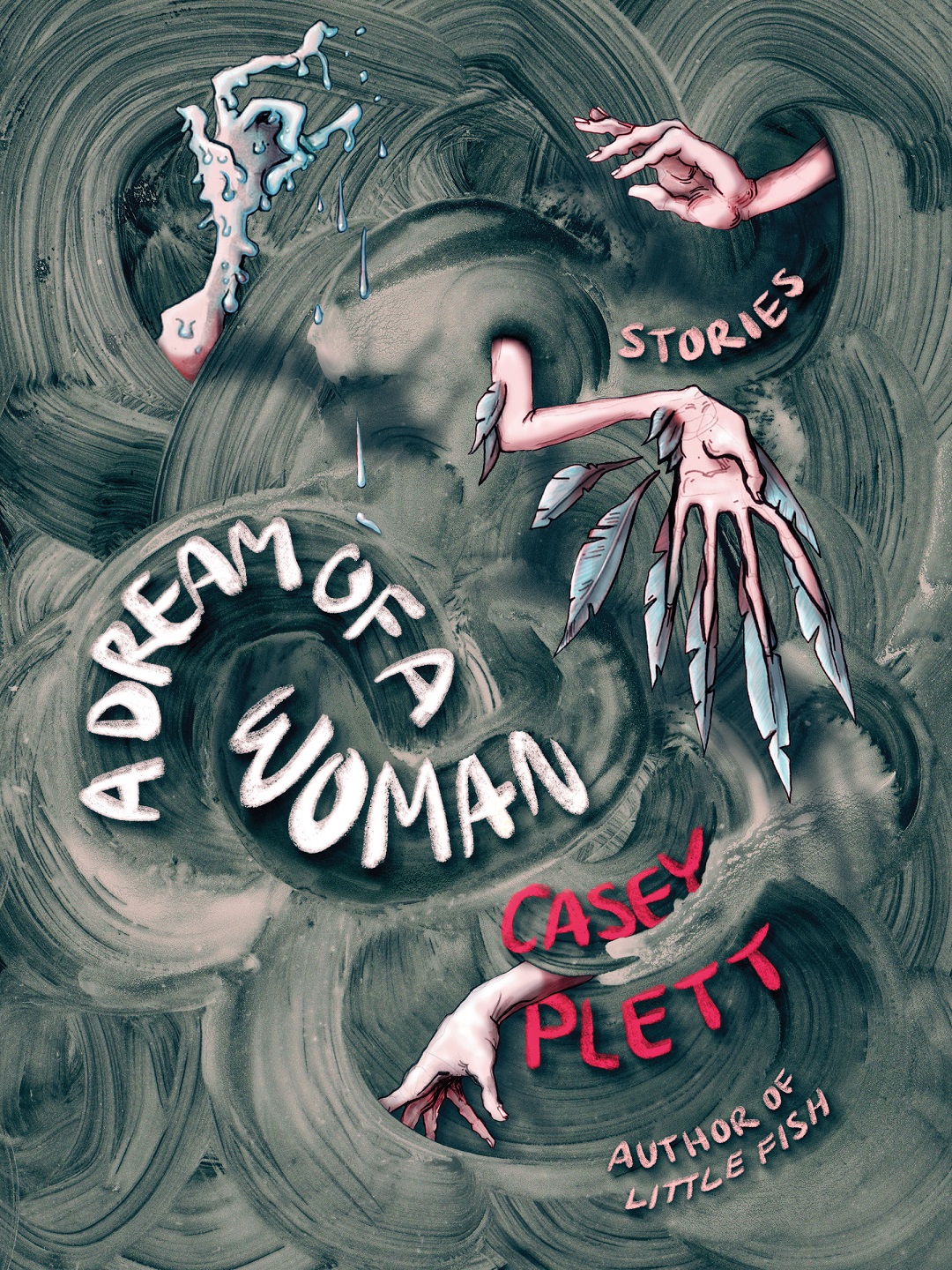

I admit to being nervous to interview Casey Plett. We’re talking over Zoom, her in New York and me in my home in Toronto. Ostensibly, we’re gathering to discuss her new book, A Dream of a Woman, a collection of short stories centring trans women. In all of her work, including her most recent novel, the award-winning Little Fish, she has made trans women the focus, both emotionally and physically.

Winnipeg-born Plett has become a trans lit icon, her name carefully written on notes passed to newly-out trans girls that say “To Read” at the top. Her career has had its lens focused on trans lives, drawing attention to the angles and sides we don’t always see.

Credit: Courtesy of Arsenal Pulp Press

It’s a delicate line to walk, telling trans stories. One step over the line and you run the risk of universalizing the trans narrative, reducing trans women to simple platitudes. Plett’s stories place her characters on unique paths, drawn over maps of cities well lived in. Blink and you might miss a passing reference to an old SAAN store, a now-defunct chain of Canadian department stores that sprang up in Manitoba before proliferating out to small towns nationwide. Small details make the worlds in Plett’s stories feel both wildly unique and immediately accessible, a tendency she picked up at a young age.

“I remember reading Philip Roth. When I was 13, I read Portnoy’s Complaint,” Plett tells me, “which is all about the life of an American Jewish man growing up in New York City in the middle of the 20th century. And I had no reference for almost anything that he was referencing. This book came out in 1969, you know, very much of the zeitgeist of the time, or at least from my understanding, but I didn’t really need to because it was so specific. And it was so personal. And because it was so lived in.”

Plett’s career has long been about creating worlds filled with details—large and small—for trans women to exist in. Her remarkable debut, A Safe Girl to Love, was published by the now-defunct Topside Press. It’s a collection of short stories about the lives of trans women, which won a Lamda Award for best transgender fiction in 2014. With the collapse of Topside, the book has gone out of print, though it lives as a free PDF on Plett’s website.

Following A Safe Girl to Love, Plett wrote Little Fish, a story about a trans girl from a Mennonite family in Manitoba who discovers that her deceased grandfather may have been trans himself. It’s an enthralling and hauntingly beautiful novel that drove home the idea that Plett is a writer with a powerful voice rooted in the soil that nurtured her. It also cemented the idea that trans writers can write to much success for their own communities, even when those communities feel small.

“That book is very much about the city [of Winnipeg] and, in a pretty big way, it’s also a very trans book,” Plett says. “Trans women who have lived in Winnipeg, that’s a very small number of people, right? And yet writing it, I would love to think of that person as the reader. And even though it’s a very small group of people, that felt so nourishing and worthwhile.”

“Relationships are built and falter, people struggle with addiction, boundaries are tested and sometimes broken—all elements of the runaway train that is growing out of your 20s.”

A Dream of a Woman is a return to the short story format, but we are now witness to trans women as they approach and struggle with adulthood. The stories focus on individuals navigating adult lives they never fully prepared themselves to have. The opening story, “Hazel and Christopher,” introduces us to two childhood friends as they reconnect and navigate love after transition, while “Couldn’t Hear You Anymore” is a reflection on trauma and the distance it creates between people over time. Through the eight stories in A Dream of a Woman, relationships are built and falter, people struggle with addiction, boundaries are tested and sometimes broken—all elements of the runaway train that is growing out of your 20s.

Central to the collection is “Obsolution,” a story in five parts that cuts in and out of the other stories, weaving its narrative around the lives of the other characters living in the text. “The protagonists, I think, share a lot of dispositions and trouble and foibles and struggles,” says Plett. “I think of the book as having two separate tracks that way. ‘Obsolution’ is one, and the characters of all the other stories are all another.”

Where the collection’s other stories focus primarily on trans women in their 30s, we meet the protagonist of “Obsolution” when she’s young; in every iteration of her story, she has aged since we last left her. “I’m intrigued with the idea of the recursiveness in trans lives,” Plett says. “All of a sudden you wake up and you’re like, ‘This thing has been the same for the last 10 or 15 years.’ What the fuck is up with that? Maybe some things look so incredibly different and you think, ‘Holy shit, I never could have imagined that.’ Some things, if you had told me I would still be dealing with them 15 years ago, what would I have said?”

“The number one thing I would want for any trans writer is to be able to write whatever is moving you, whatever is compelling you, without necessarily needing to feel like you’ve got to either wedge or not wedge your transness to whatever degree you don’t want.”

Often, Plett’s character never imagined themselves inhabiting the spaces in which their bodies now stand. In “Perfect Places,” Nicole is a trans woman questioning her desirability while in a difficult, fetish-based relationship with a man. Nicole is understood to be a trans woman, but it’s never spelled out so bluntly. “Transness is an important part of the story and an important part of her, but also lots of pages can go by without it necessarily coming up or without me feeling like I need to really address that as an author,” says Plett.

I ask her about where we are in the history of telling trans stories, if we’re in a place where we no longer have to shout “trans” from every page. “The number one thing I would want for any trans writer is to be able to write whatever is moving you, whatever is compelling you, without necessarily needing to feel like you’ve got to either wedge or not wedge your transness to whatever degree you don’t want,” Plett says.

Both Little Fish and A Dream of a Woman have narratives about addiction, where characters drink alcohol and opine about the nature of their relationship to alcohol. In “Enough Trouble,” the character Gemma frankly discusses the on/off nature of alcohol addiction. She tells her lover: “Stopping again is always an option, and that keeps me sane. Just like when I’m not drinking, I know starting again is always an option, and that keeps me sane, too.”

“When I really wanted to start talking about addiction, I started feeling very frustrated,” says Plett. “Every story that I saw ended up with these very bifurcated endings, that either ended with someone being sober and happy—both had to be one and the same—or not sober and dead or dying. And every day people who have addictions wake up and don’t necessarily fall into one of those two categories. I want to talk about it in ways that felt more complicated and nuanced than the usual media portrayals.”

“The pain is just a by-product of wear in a life that belongs only to the bearer.”

Plett’s characters work because they are whole, made so by their flaws and downturns as much as their triumphs and successes. Her treatment of her characters shows us clearly the cracks and the scars that have made them. Of course, it’s easy to see the pain in trans lives when, far too often, mainstream portrayals of transness suggest pain is all there is. Yet, in the stories that Plett lays out for us, the pain is just a by-product of wear in a life that belongs only to the bearer; a comfortable pair of Italian leather boots that started life so rigid and unbearable, but softened to become cherished and beloved.

Like so many tall girls before me, I was given a note with “Casey Plett” written under the words “To Read.” It was her work that gave me hope in the early days, as I read stories of characters that felt like precious gems with minor chips and scratches on them. Beautiful and wondrous, but never wholly perfect.

I’m nervous on this call with Plett because who could be calm when talking to someone that helped make your life feel real, even the parts you thought were broken? Through my own struggles and hardships, she answered my desperate need for stories that reflected the reality of my life back at me, instead of selling me an idealized version of trans life. Plett tells beautiful stories of trans women as they exist in the world: tangible, fallible, tender and hardened.

A Dream of a Woman will be published by Arsenal Pulp Press on Sep. 21, 2021.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra