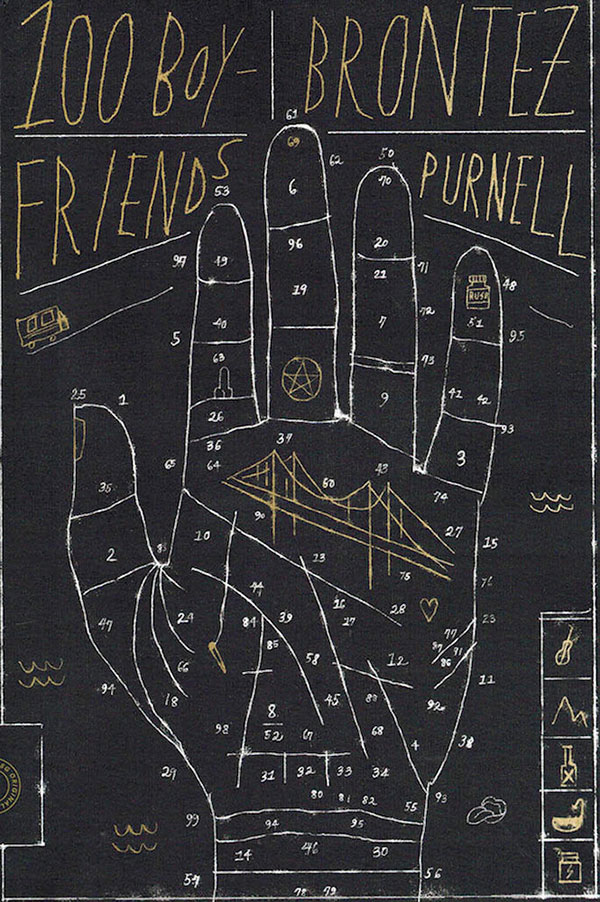

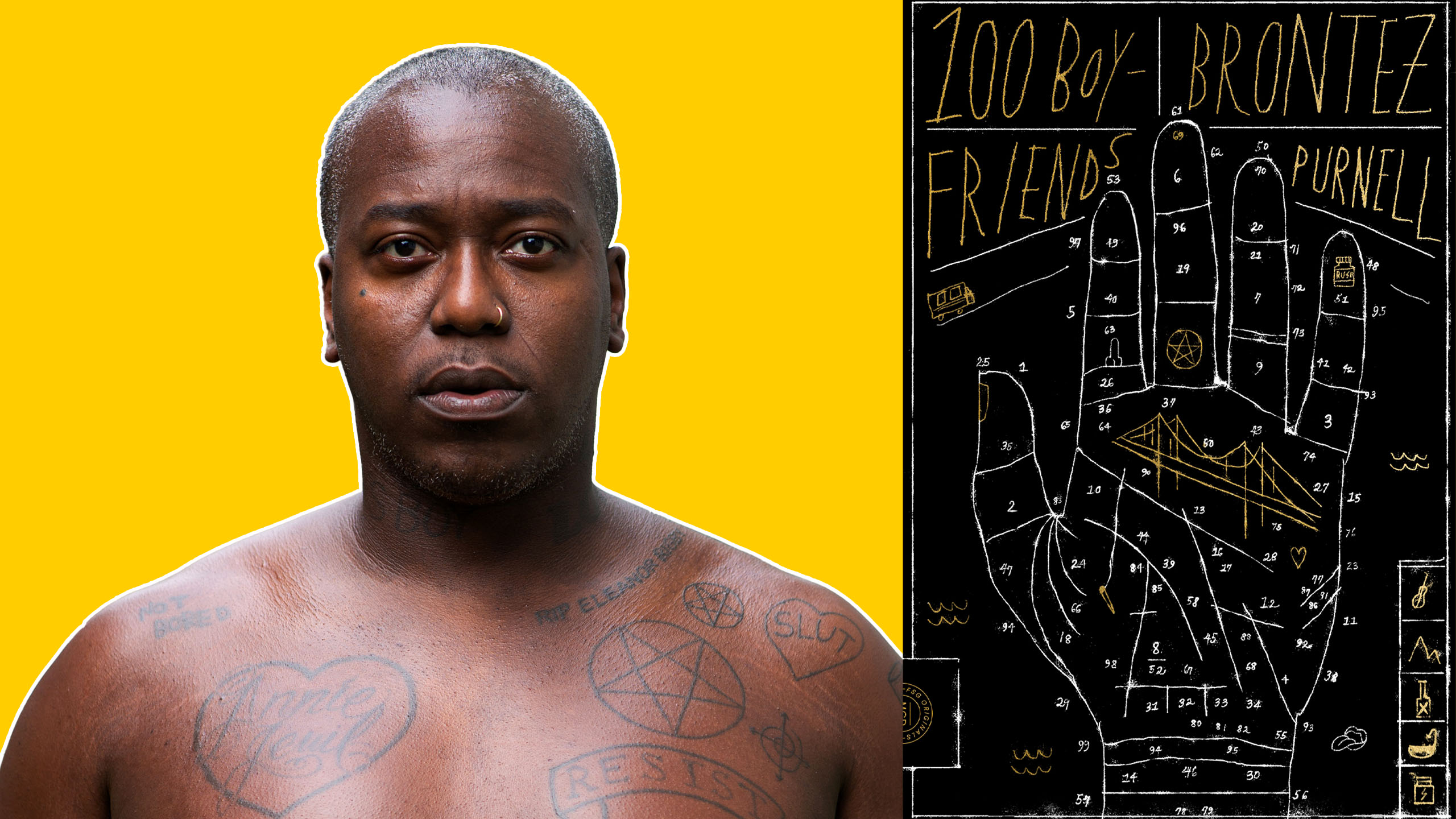

“I really think some people really hated it,” Brontez Purnell says about the response to his book 100 Boyfriends. Since its February 2021 debut, the tantalizing collection of short stories that chronicles the messy and chaotic lives of Black queer men as they get older has been a polarizing text, to say the least. On one hand, it has received critical acclaim, including a nomination for a Lambda Literary Award, the winners of which will be announced June 11. On the other hand, some readers on review sites like Amazon and Goodreads claimed they couldn’t relate to the non-traditional storytelling structure and the stories about hooking up, casual sex and drug use. And certainly the book was a lightning rod for anti-Black trolls who admonished the book.

To me, though, when I first read 100 Boyfriends, I found it thrilling, having located a familiarity in the slutty characters, some of whom are HIV-positive. I also identified with the spectrum of sex and relationships depicted, ones that were sometimes good, sometimes weird or otherwise unsatisfying, dangerous or complicated. Upon a second read, however, I developed an even deeper understanding of 100 Boyfriends as a book ultimately about love and how gay men treat and care for each other as we age. I also recognized how so much of the criticism the book has received is less about what’s actually on the page and more about an unfamiliarity with the world that the author is writing about, and where to place it in relation to other stories.

When I think about the space that Purnell’s book exists in, a video by the artist Derrick Woods-Morrow comes to mind. Titled Much handled things are always soft, and commissioned by Visual AIDS in 2019, the video is an intergenerational conversation between Woods-Morrow and Patric McCoy, an art collector and long-term AIDS survivor. They work together to construct a monument to cruising and public sex culture as they discuss the history of how Black men found sex in the parks of Chicago at the height of the HIV/AIDS crisis. At one point in their conversation, McCoy discusses how even though cruising was largely condemned because of shame and homophobia, the community still thrived. Woods-Morrow suggests that he’ll continue working toward a mainstream acceptance, a comment that makes McCoy chuckle and admit that Woods-Morrow is on his own in that crusade. “You’d rather it stay hidden?” Woods-Morrow asks. McCoy responds, “I’d rather it stay at a level [that’s] sittin’ right on the horizon. It’s not hidden.”

It’s that same horizon from where Purnell’s work grows and where his characters exist. It’s not a hidden space—if you’re looking for it, or are already part of it, you’ll see and be able to identify with it. But if not, perhaps one might find the work confusing. Or perhaps the complexity, necessity and importance of the characters Purnell writes, characters who may be Black, gay, HIV-positive, poor, drug users or, as he describes, part of a “criminal class” largely under-recognized on both a literary and a societal level.

Ahead of the Lammys, Xtra caught up with Purnell to discuss 100 Boyfriends’ reception and love and relationships. We also discuss how his film and performance work connect to his literary work, and the ghosts he writes for.

I’ve been thinking about the title of your book, and how “boyfriends” being plural might suggest going through relationships quickly, or polyamory or non-monogamy, which some people might misconstrue as frivolousness. But I read this book as a book about love. What was your intention?

I feel like so much of our language, especially now, is to name everything as clinically and as coldly as possible. There’s something about this book that I think is totally even beyond polyamory, beyond non-monogamy. There’s, like, monogamy, right? Which we all just grew up with, but we didn’t have a strong basis of what that is. It’s like “if you look at my boyfriend, I’ll fucking cut you.” Yawn! Whatever! But there’s this idea that polyamory and non-monogamy are just these carefully contrived choices that we make, and that we make the point to talk to everyone we’re involved with about everybody else we’re involved with and it’s so scientific and so fucking boring.

But beyond that, I feel like—especially as I get older—there are lovers I’ve had for years where it would be so complicated at this point in my life to just find one person and walk off into the sunset with them forever. Because in a marginalized sense, in a weird queer sense, my life was always dependent on my needs, and also the network of people needing to depend on me. There are boys whom I’ve been in love with since my 20s where we’ve never had sex once, but they know I’m in love with them and they lean on my emotional labour intensely. We’ve made this dynamic. How exactly do you describe it in a polite way? In a concise way? You can’t. But the paradoxes exist because we exist. There are my straight girlfriends—I’ve totally married them because all the men we know are garbage and we’ve had to stick together and be each other’s emotional backbone. When we talk about being queer, it’s a lot of messy things that are just not easily explainable. Essentially, I do feel like I am a boyfriend to 100 people. It’s not just an acquaintance. I have to be accountable. I have to be on point. I have to be emotionally available. If something bad happens to that person, I might have to be monetarily available. You know what I’m saying? I hold this space, like a partner, for lots of people in my life who don’t have one. In a system that leaves us all single and vulnerable and easily exploited, we need that. So I like to talk about these kinds of perilous lines of love and how hard they are. But then also, how exhilarating it is, when you really think of, in the purest sense, the network of people looking out for you.

The book has this three-act structure and there’s an epilogue. I’m interested in the differences between these three acts and why you made the decision to structure it this way?

The first act is Army of Lovers and it’s like the Sacred Band of Thebes: an army of lovers can’t be defeated. The second act [100-Page Breakup Letter] was based on Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis. So it’s like, Army of Lovers is about men you love. 100-Page Breakup Letter is about men you hate. And then the [third act] is the manifesto, No New Boyfriends, and it’s about the boyfriend within. But also keep in mind, all of the stories are interchangeable under those umbrellas. I just like threes and trilogies and the three-act structure was always compelling to me. Plus I annoyingly have a theatre degree, so I’m always thinking in those terms. It was a way to just finally get that out of my system for once. I’ve always wanted to write a piece structured like that. It was the only real way to separate the light text and dense text.

I know that you’ve done a film series called 100 Boyfriends Mixtape. Can you talk about that work and the relationship between that film and the book?

I like to explore one idea in a plethora of contexts. The monologue from that video [100 Boyfriends Mixtape (The Demo)] was actually from a performance night I did with my dance company [Brontez Purnell Dance Company]. The middle piece [of the performance] is what you saw in the 100 Boyfriends Mixtape (The Demo). That video is actually number two [of the mixtapes]. The first 100 Boyfriends Mixtape is with Naked Sword [the gay porn platform]. I was in this indie rock porn movie called I Want Your Love years ago and Naked Sword liked the job that I did, so they asked if I had a script. In 2014, I turned 100 Boyfriends Mixtape number one into a video for Naked Sword. The second one [you saw] is also available on the Criterion Channel. The third one was commissioned by Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, where it hasn’t had any type of actual release, but it’s in that silo]. There was something about the idea of episodic performance videos that went all over the place that I liked. I liked that it pivots between Naked Sword and Criterion and it’s kind of like, “What the fuck?” But I feel like it’s separate because the written word just becomes so different to me. Writing about something is so isolationist, whereas every other piece of art I do is communal. I really depend on 12 other people when I want to make music or when I want to make a dance, or when there has to be a performance. Of course, the themes are brought up, but the films are a character study that I think is so very specific. Whereas 100 Boyfriends, the book, really contains a wider swath [of storytelling]. Writing is really two-dimensional. Writing always gives the illusion that there is order. For instance: “I burned my hand on the stove. Ow! I need to soothe that. Where’s the ice?” These thoughts automatically become a line, as opposed to when it actually happens, all of those thoughts are racing together at once. All those thoughts racing together at once is better contained, I think, in a movie or something, because you can get to that a little better. With writing, there’s just no real way to do that.

You mentioned that some people didn’t like the book and weren’t into it. I’m assuming this means that you’ve read some of the reviews ….

Anti-Blackness is so real. If somebody gives you a five-star review, here comes that white troll right under their leg that’s like, “Well, what makes this book so special? I think blah blah blah! I think he’s all over the place!” Essentially, they’re going to sit there and explain why you aren’t writing like their favourite white writer. I don’t expect everybody to like me. But I’m also not going to sit there while you play me out for some dumb reasons. As a person of colour, as a fringe artist, I have been told that I don’t know shit about my experience, my entire fucking life. Every time somebody comes at me over material that’s this sensitive—specifically gay, Black faggotry—every time someone outside my fucking very close bubble tells me that I did a bad job at this, I’m always in my head like, “Okay, well. Who the fuck was supposed to write this—you? You tell me what this was supposed to be like.” I’m an artist and I’m sensitive about my shit. I want to be able to accept critique graciously, but I also know that it’s not always coming from a gracious or generous place.

Once work steps outside the realm of the community or spectrum of people written about, I often wonder if those critics actually know what they are critiquing. Not to be mean, but I do wonder if they have the range for it. I’m really starting to think that they may not.

They might not have the range for it, but will swear up and down the day that they do. And like, there are a lot of fucking criminals in my writing. I’m writing about a criminal class. It’s all a very sensitive spot and I’m very very protective of it. I feel like what I’m generating from and what we’re talking about is a class of people who are very, very unprotected. So I can be damn right bloody about their right to exist and this writing’s right to exist.

When we last spoke, I asked you a question about who you have in mind when you write and you said that you write for ghosts. For me, “ghosts” implies a particular haunting and stories about ghosts often revolve around unresolved issues. Is your writing trying to figure out an unresolved issue? Is there something in the topics or even this title that you’re still trying to reconcile or figure out?

I wouldn’t call it unreconciled. At this point, I would call it irreconcilable. It’s a problem that you kind of just don’t really fix. I don’t know, maybe this is the work, or this is the practice or this will always be the case. I was writing from that sense.

I think drama is there to create questions and go to questions about conflict. Deep, irreconcilable conflict. I think it’s something that we will always be confronting. I think if drama writers had solutions to all these problems, we would be writing self-help books, not drama.

I feel like it’s always this line in the sand that you’re constantly drawing and redrawing and repainting and re-sketching. There’s something about it that feels like an openness of sorts. It’s kind of like Mary J. Blige’s music. It’s only up until the third or fourth record that she’s singing about how men treat her bad because by the time you’re in your 50s, talking about men treating you bad just doesn’t hit in the same way. You saw how she [pivoted] to “My life’s just … / Fine, fine, fine, fine, fine, fine, ooooh.” I feel like there comes a point where you’re supposed to be aiming toward that. You sit in the deep trenches of whatever question it is you have about reality and after you ask the hardest fucking question, there should be some sense of resolve, some kind of moment, some type of movement toward peace or a light at the end of the tunnel. Or maybe it’s a return to darkness? It feels like after this kind of fever pitch, there’s a pivot somewhere. So right now, I’m at that stage of being like, where does it pivot to?

One of the reasons why I think this particular book is so special is because when we talk about queerness or gayness, the dominant stories tend to be very stuck in this place of coming out—baby queer people in their 20s learning to be themselves and be free, and it’s a bit of a party. I love that, but I think you take it a step further to where it’s the next day and the party’s over.

It’s post, post, post-Euphoria girl, right? It has not felt euphoric in a minute.

Yeah. It’s sort of this weird space of having to negotiate what life looks like and what the experience looks like. I’m asking myself, like one of your characters asks himself, “Am I really choosing to be this person?” That’s what is special about this book, it’s about figuring out the person you’re going to be, with all the inevitable baggage and stuff that you’ve accumulated across a life.

And who you’re going to be with when you’re being that person. Totally.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra