I love matching books to people; identifying the perfect story for a friend in need right now is one of my love languages. I adore finding just the right protagonist in a novel to offer a dose of courage. My nerd heart swells at offering the best fitting research material for an obscure subject. And the part of me that just wants to wrap everyone in a giant, soothing hug is delighted every time I find a genuine, realistic, heartwarming read. It’s not about being saccharine—it’s about meeting the ups and downs of life directly, with compassion and grace.

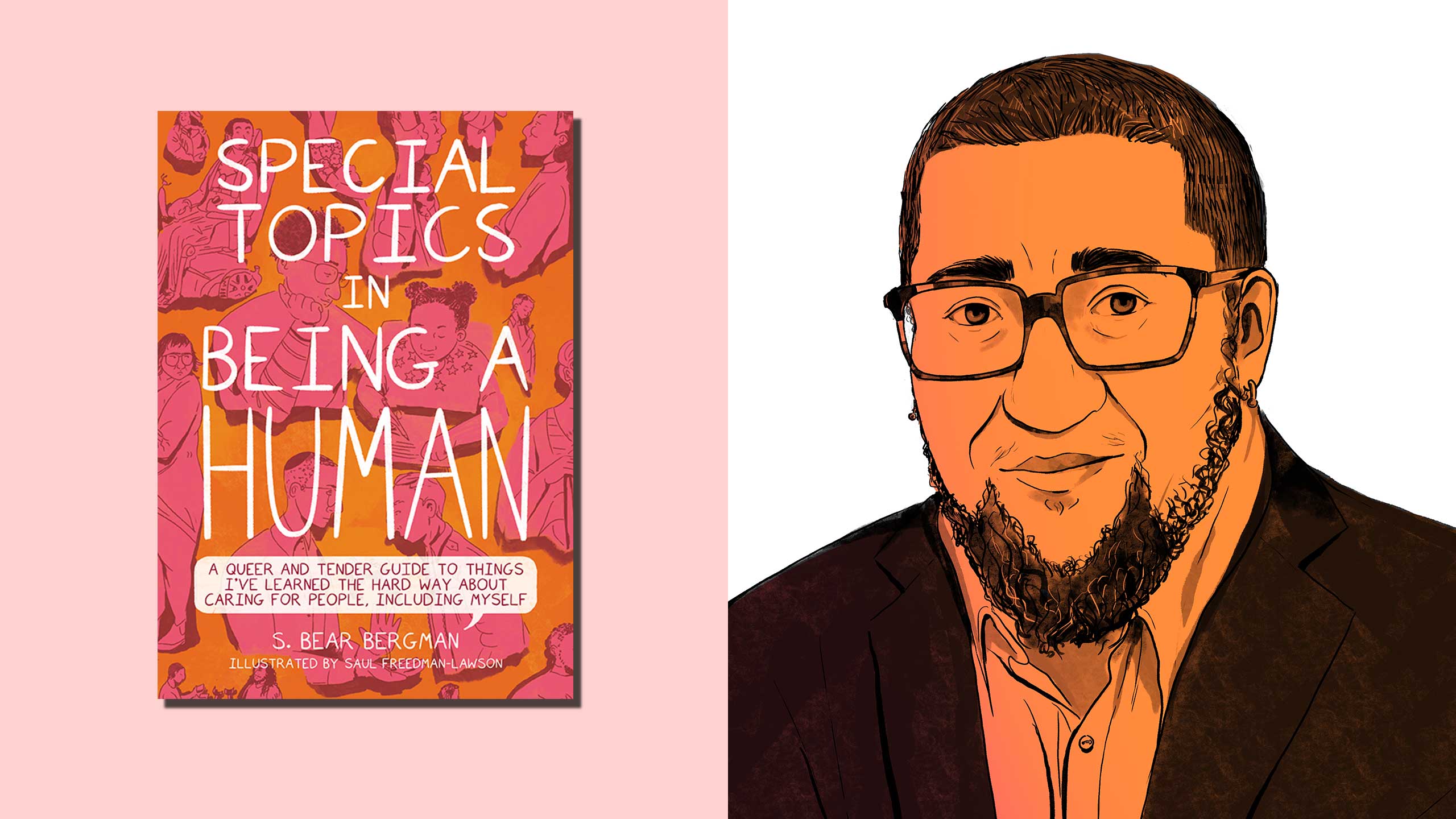

So I was thrilled to read author and Xtra contributor S. Bear Bergman’s new book, Special Topics in Being a Human: A Queer and Tender Guide to Things I’ve Learned the Hard Way About Caring for People, Including Myself. It’s the hug and the cup of tea you’ve always needed from a street-wise and kind-hearted queer uncle. For example, the chapter titled “How to Love Someone with Your Words, Actions, and Priorities (in Addition to Your Feelings, Which I’m Sure Are Very Nice)” reminds us that love is something you do, a kind of magic that grows through taking concrete steps to care for each other. Special Topics is beautifully illustrated by Saul Freedman-Lawson, and the art brings the advice to life in a breathtaking way (it’s worth getting a physical copy of the book).

Xtra caught up with Bergman about the process of creating an illustrated advice book, the frustration of receiving “just be yourself” as advice and the power of intergenerational queer friendships.

How did you arrive at the title Special Topics in Being a Human?

It honestly started as a bit of a joke. I have the advice column “Asking Bear” that I’ve been writing for about five years. You know how it is when you have a regular column to write: you keep a file of anything you make or come across that you think might be useful to you. I had this one outlier I had written as a favour to a friend who was struggling with something that I really struggle with. This outlier became Chapter 5, “How to Avoid Getting Your Upset All Over Other People When You’re Feeling Out of Control.”

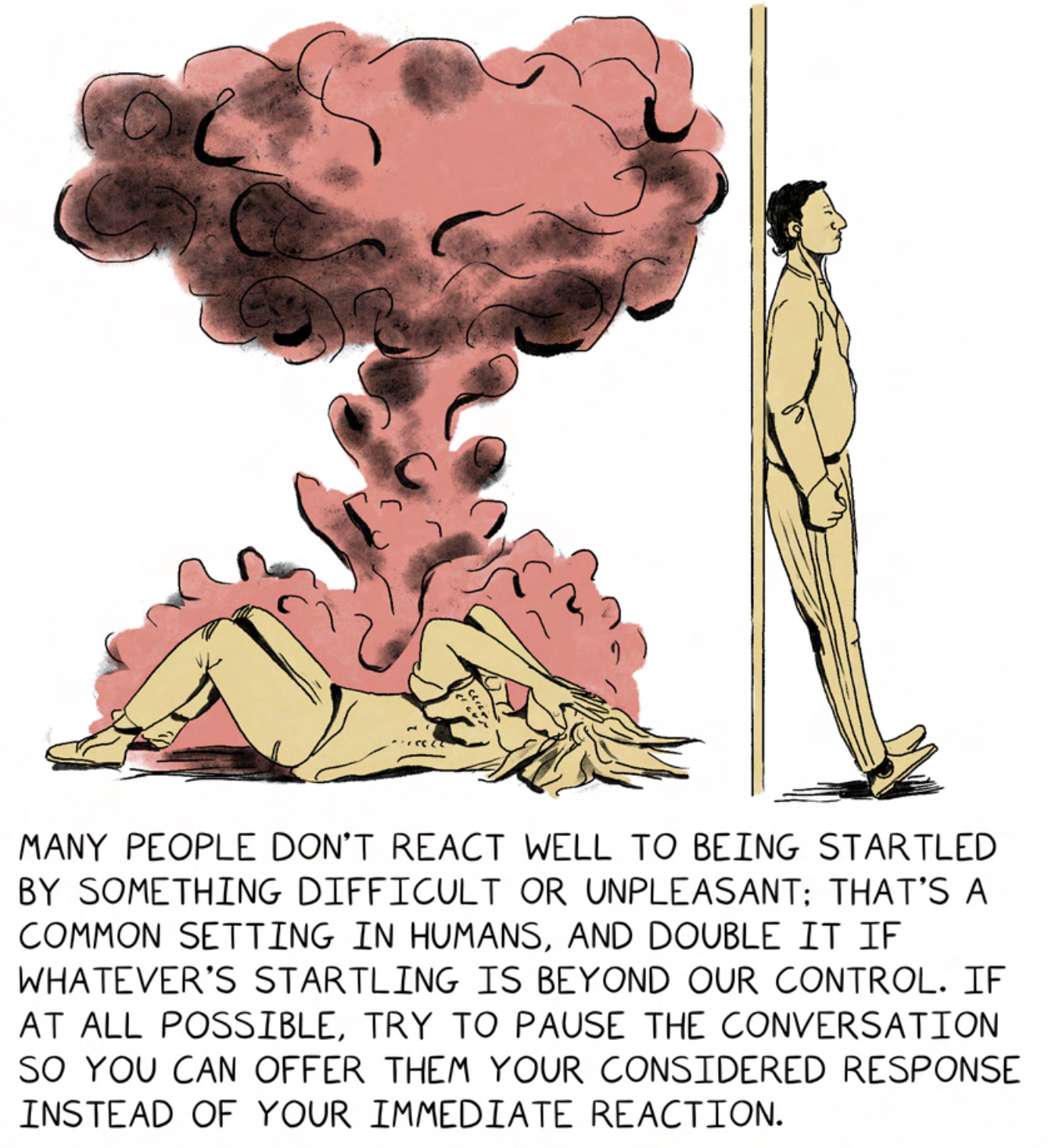

Then Saul, the illustrator, was over for dinner, and my husband was doing work about how when you present difficult or potentially challenging information with illustrations, it lowers people’s resistance to it. The art invites a sense of playfulness or curiosity that can be hard to access under other circumstances. On a whim, I said to Saul, “I have this one piece I want to put in the advice column, but I can’t figure out how. Would you be open to giving a try at illustrating it?”

I imagined writing plus illustrating would be like one plus one equal two. But when Saul came back with the illustrated piece, I thought, “One plus one equals 11 in this case. This is amazing.” So I put it up on the website, and I needed a name for this genre of post.

Off the cuff, I said, “Let’s call it ‘Special Topics in Being a Human’”—the way advanced university classes will have that as a title.

People were wild about it. It got such a great reaction.

And I was like, “Hey, do you want to do another one?” And he said, “Yeah, absolutely.”

Credit: Courtesy of Arsenal Pulp Press

What did it feel like for the two of you doing those first ones?

I didn’t give any instructions or illustration notes at all—we were just playing. He’s a talented illustrator and he’s familiar with my work and my audience.

That’s basically how we did the whole book: I would write things, I would send them to Saul, he would illustrate them. As you now know, having read the book, my talent in the visual arts is minimal at best.

“How to Be Bad at Things but Do Them Anyway” was a favourite chapter because it’s so common to go, “I can’t do that. I’m bad at that.” It was wonderful to have you two switch writer and illustrator roles in that chapter.

Thank you. It was definitely a challenge for both of us. I’d gotten a letter from someone who wrote, “My co-workers are going to a wine and painting night where we’re supposed to drink and paint pictures. And I’m a terrible artist and I don’t know how to go and have fun without being self-conscious the entire time.”

I had written a response saying, “We have to be bad at things before we can be good at them. And that’s hard to do as an adult, but it’s worthwhile. So give it a try.”

I said to Saul, “I think we should do a chapter where we switch jobs and I’ll do the illustrating and you do the writing. And it’ll be about how to be bad at things, but go ahead and do them anyway.” And we both put it off until the last minute.

We were both like, “Maybe I will magically become a better artist if I just wait a little longer.” Which, as you can clearly see, did not happen, but it still felt valuable to put it out.

Exactly. And it made it relatable. I was like, “Oh, I can draw like that too.”

I mean, all the drawings are recognizable. That’s probably the most you could say about them. Lynda Barry, the cartoonist, is an absolute genius. In her book, she recommends that if you draw a cup of coffee and you’re not sure it’s clear, just put an arrow and write coffee.

I think of visual art as akin to magic. With Saul, I was like, “Oh, you just go into the magic cave of talent and you make things look on the page like they look in real life.” I felt no desire to try to say, “You should draw it like this,” because I know that I don’t know. So I was just like, “Have fun. Good luck.” Like, I’m dropping my kids off at school. “Love you, enjoy. Whatever happens, happens.”

Are there any other chapters that really surprised you or stood out to you along the way?

The chapter “How to Be Yourself.” It came very slowly and it changed a lot while I was writing it. It was one of the earliest ones that I started and one of the last ones that I finished because I found that I kept wanting to say more.

I feel like I’ve been told “just be yourself” about queer stuff and trans stuff as long as I’ve been out, which is now a very long time. But of course, you can’t always just be yourself. That’s not actually how the world works. It’s a nice idea, but we can’t really always do that.

That chapter ended up being very different than what I initially expected or intended. I feel very tender about it because it’s a big piece of work the chapter is asking people to do. But I’ve heard back, now, from some people who’ve tried it, and it turned out to be good for them, which was great.

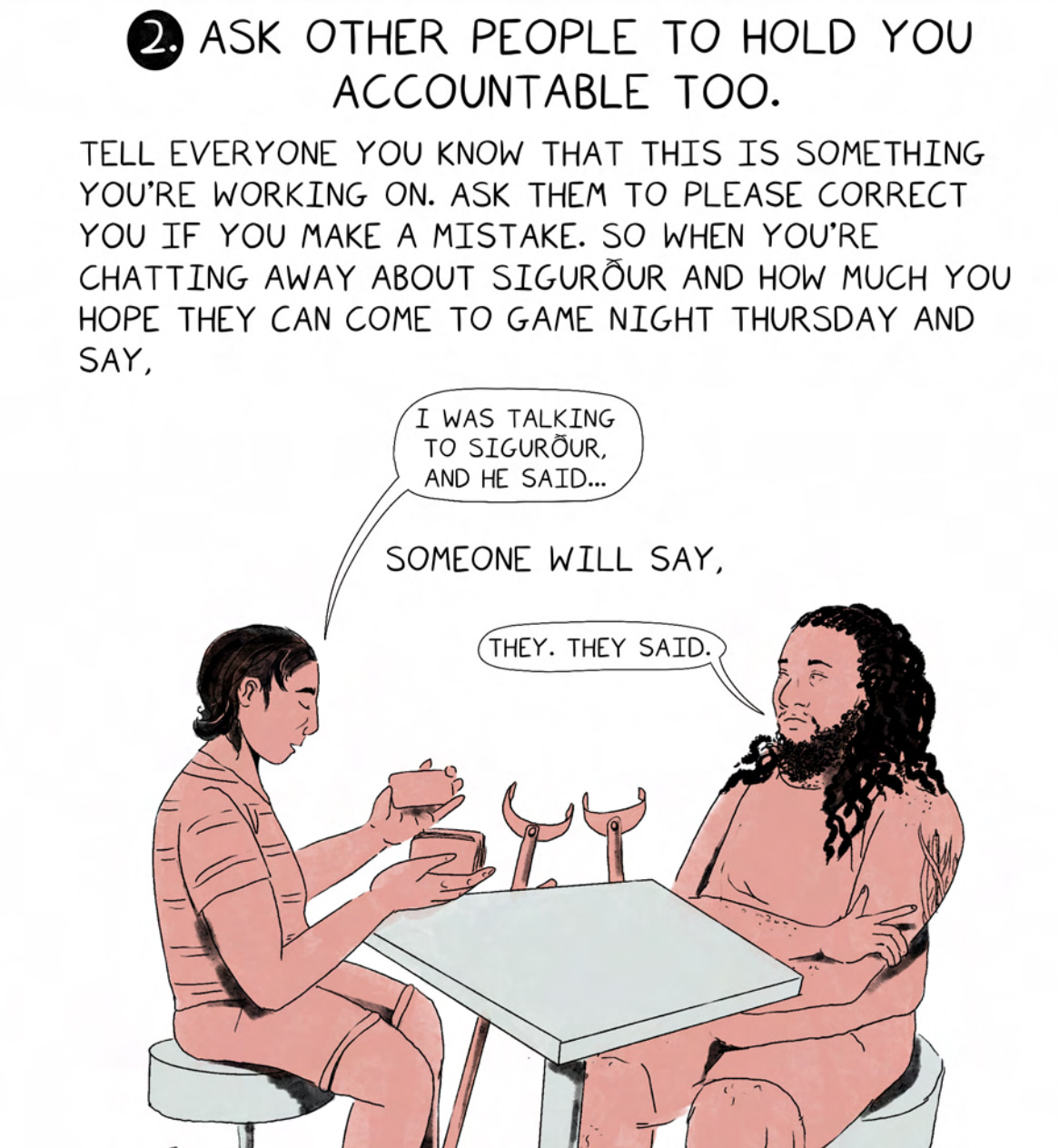

It’s a little difficult, right? It’s like asking: Who’s your favourite child? I’m fond of all the chapters in different ways. But some of them are emotionally not very complicated, like the one about how to give the right kind of help. Even though it’s something that I definitely mess up, often, it’s also a piece of advice that I’ve had a lot of opportunity to share with people. First, validate, then give credit, then problem solve—but not too soon. I’ve talked about that for literal years in my advice-giving and in my private life. That one came out easily, all in one piece, right at the beginning. Same with the chapter about pronouns.

Some of the others, especially “How to Be Yourself,” developed more slowly. And that process for me was like, “Oh, this is a little hard, but not unpleasant.”

It’s like a warm hug. It’s like saying, “Hello, baby queer, baby trans, baby person, I see you, I believe in you, it’s all going to be okay.”

I love that. I didn’t want to be like, “I, a person who is wise, will now tell you, a person who is not, what you should do.” Instead, it was more like, “Oh, look at all of these mistakes I have made so you don’t have to.” That was almost the subtitle of the book. And then it became A Queer and Tender Guide to Things I’ve Learned the Hard Way About Caring for People, Including Myself.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about intergenerational queer and trans friendships. It’s just beautiful to have artifacts in addition to conversations.

Yeah. I came out quite young for the early ’90s. Back then, it was a lot less common to have out 16-year-olds. I came out into a much more intergenerational, multi-identity mix of people than the 16-year-olds of today do. My queer friends were largely older and had a wide variety of identities within or beyond queerness and transness. It enriched my experience and made me continue to seek out a wide variety of people. And it helped that I did a lot of travelling to work and speak, and made friends who were not all of my age and stage.

I think a lot of people are hungry for more intergenerational and cross-identity conversations, but we struggle to know how. How do I, as a 47-year-old, make friends with a 25-year-old? How do we reconcile wildly different worldviews of what the world was like when we came out, what our struggles have been?

That’s reflected in the book because Saul is 20—he’s literally less than half my age. He’s part of my found queer family.

I wonder if that’s a thing people are able to mobilize as much as we used to. I don’t know.

“I think a lot of people are hungry for more intergenerational and cross-identity conversations.”

Just before the pandemic, I went to New York to see the play The Inheritance. It was six and a half hours of theater in two parts about the beginning, the middle and the current moment of the AIDS crisis. I invited some friends who didn’t know each other and who would have interesting perspectives to come with me. We spanned four generations: one person in their 30s, me in my 40s, one friend in her 50s and then another friend in her 60s. Everyone was queer, politically engaged, super smart.

The conversation at dinner was so fascinating. We were like, “I remember it like this.” And then, “Oh, I didn’t join that until this thing.” It was this lovely cross-pollination, getting a clearer sense of each other’s context, how we each arrived a certain way into queerness.

I enjoy all the opportunities that I have to be with multiple generations. And I think a lot about how to make more of that happen when we can see each other again.

Has Special Topics taken you anywhere yet? We’re still in weird pandemic times.

Not yet. I’m hoping that we’ll be able to tour in the spring, but it’s not clear. I have three kids, two of whom are still too young to be vaccinated. I mean, I’ve done some great online events—one with Kai Cheng Thom from Xtra and one with the writer Alicia Elliott—but I haven’t had the chance to do in-person events.

In the fall, I wrote an article for Vice about queer bookstores, and I talked to a bunch of people who are opening new ones. And I was like, in my secret heart, I really want to do events at all of these new queer bookstores—and all the ones that I already know and love from having been a writer for, whatever, a million years—but especially all the bookstores that have recently opened up.

That would be like a housewarming blessing for them.

I mean, for me too. I’m so happy that there are more queer bookstores opening. There used to be so many and then high-speed internet porn happened and then Amazon happened, and then nobody needed their local queer bookstore anymore.

Credit: Courtesy of Arsenal Pulp Press

I still make pilgrimages. I saw your book in Bluestockings and I pulled it out and I was like, I get to read this one and I get to do an article about it and I’m so excited.

I love them over there.

Is there anything else you want to talk about book-wise?

The subtitle is A Queer and Tender Guide, and the book is for everyone, but the queer lens does a portion of the work.

We get all of this information from the macro culture about how we are supposed to conduct ourselves. For some of us, it doesn’t suit, it doesn’t fit what we need. Mainstream messages are actually not serving very many people. As a queer person, as a trans person, I learned really early on that I couldn’t rely on media to figure out what to model my relationships on. I couldn’t rely on “Dear Abby” [Abigail Van Buren] or Ann Landers to give me good advice. Their advice wasn’t going to be applicable to my complicated queer relationship situations.

[The book is] also very queer in the illustrations. We did a lot of work to make sure that lots of people would see themselves reflected. It’s not just couples. There are triads and other polycules. A lot of different people’s experiences are visually represented as well as represented in the text.

I think that’s part of what makes it feel so warm, that I could see myself in my constellation of lovers, friends and chosen family in there. I didn’t have to explain myself or try to adapt advice that’s geared toward a straight, monogamous couple to me and my life.

Yeah. I mean, that’s the goal. I’m super glad to hear that it went well for you.

I still feel very, very tender about the book, partly because it’s not like anything else and partly because I reached for a lot of stuff while I was writing it. So every time someone says, “I read this and it was really helpful,” or, “I read this and I felt seen,” there’s a way in which, more than any of my other books, I feel like, “Ooh, I helped.” I love that news.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra