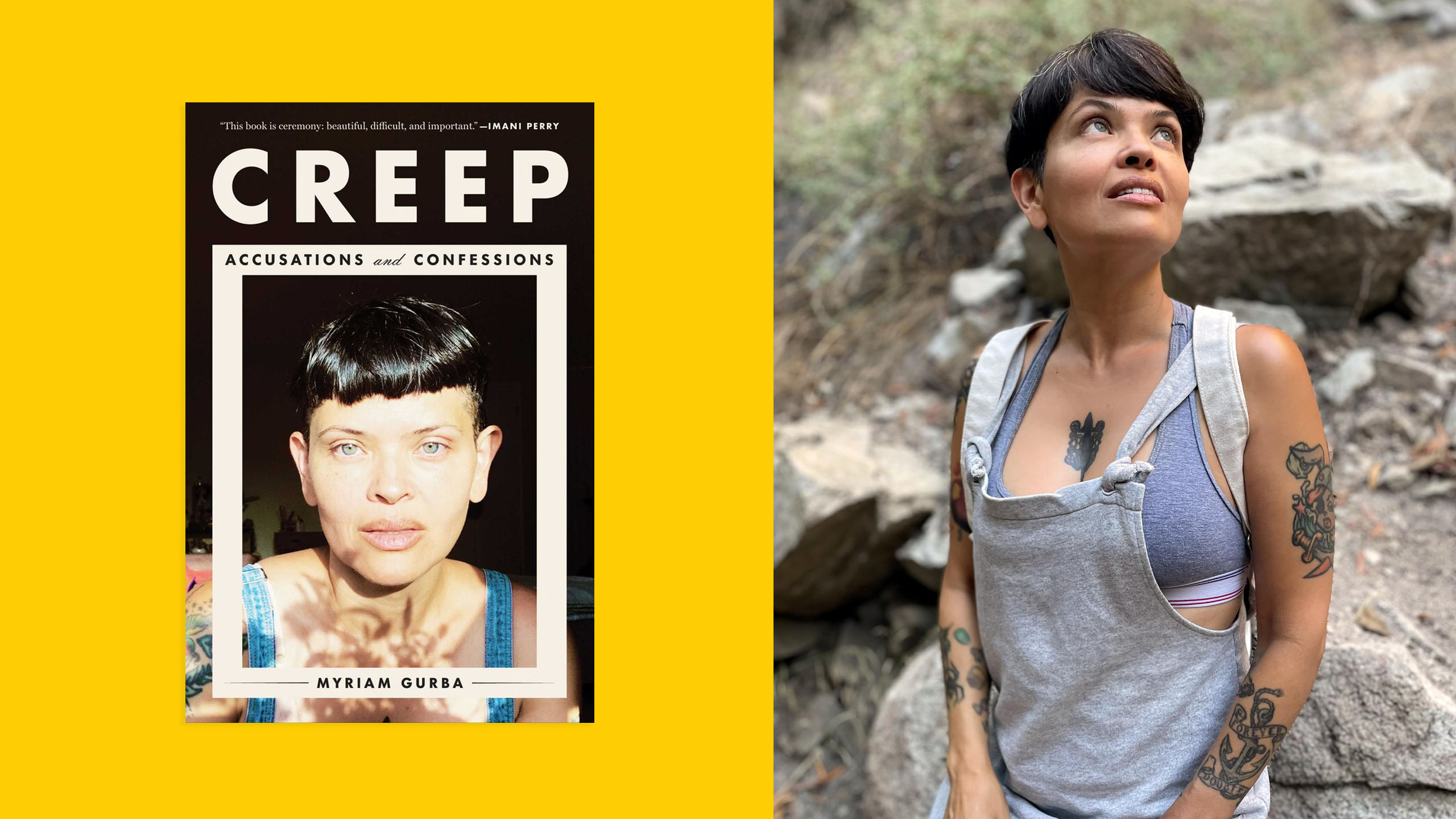

Every so often, a writer reminds us that humour and pain are indelibly intertwined, that using hilarity and linguistic playfulness to write through and about trauma and to transmit scathing analyses of rotted power structures is valid, necessary and an act of resistance. Often, these writers are queer. I’m thinking of Brontez Purnell, Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore and Rabih Alameddine. Myriam Gurba is top of the list: this was obvious to me ever since I devoured Mean, her 2017 true crime memoir—a memoir in fragments about growing up queer and Mexican in California in the 1980s and ’90s, about sexual violence and the ghosts it leaves behind. You know it too if you follow her on Twitter, where her takes are always spot-on, or if you read her precise and devastating takedown of Jeanine Cummins’s infamous white-saviour-migrant-trauma-porn novel American Dirt, included in her new essay collection for your enjoyment—I love a literary pan, especially when it points to the glaring hypocrisies of so-called diversity in publishing.

Don’t get me wrong. Creep: Accusations and Confessions is also an incredibly generous, warm and sensorially rich text. The 11 essays are maximalist in their approach, packed with detail and startling connections that will have you seven layers deep in a Wikipedia hole and scribbling wildly in the margins as you read. Gurba springs easily from one topic to another, from historic figures to Gurba’s own memories: from California to Guadalajara, from Chavela Vargas to the origins of magical realism, from the carceral state to high school classroom banter and the domestic violence that haunts the centre of the book.

The concept of the creep anchors the collection: who is the creep, how does the creep operate and which structures enable the creep to exist and to maintain power? In these pages, the persona of the creep is embodied by a wide array of figures: William S. Burroughs, revered for being a renegade queer beat writer, less often recalled as an abusive husband who shot his wife Joan Vollmer in the head as a party trick; Ricardo Leyva Muñoz Ramirez, the Mexican-American serial killer known as the Night Stalker, who terrorized California neighbourhoods in 1984–85, including Gurba’s grandmother’s town; Tommy Jesse Martinez, a teenage serial rapist who attacked Gurba in her hometown and later murdered another Mexican-American woman, Sophia Castro Torres (these attacks were one of the central subjects of Mean); and, perhaps surprisingly to some, Joan Didion, the white literary queen of California, whose pervasive and reductive “racial grammar” Gurba convincingly takes to task. Gurba addresses the nature of each of these creeps, while also writing about her own family, her visits to her mother’s home city of Guadalajara, and the reality of being Mexican-American and dealing with the structural and personal effects of the U.S.’s anti-Latine racism while still reminding readers that Mexico is itself a settler-colonial state.

Literary gossip and references abound: in addition to the juicy dismantling of Cummins’s ill-conceived novel, Gurba writes about her grandfather’s “frenemy” relationship with none other than Juan Rulfo, the celebrated Mexican author of Pedro Páramo, which arguably launched the genre of magical realism; Didion is compared to a white onion—“very white, very crisp, and even in death, she makes people cry;” and both Alice Sebold’s and Maggie Nelson’s writing on rape is contextualized within the structures of white supremacy and the carceral system.

Much of this is weighty stuff, but Gurba, as mentioned above, is also bitingly and frequently hilarious. Comedy is one way to cope with being a survivor of rape and other forms of abuse, she writes. Although humour is often seen as taboo when addressing sexual assault, and can of course be used by abusers themselves to minimize their actions, Gurba writes that when setting down her own experiences, she “started to think of what had happened to me as a practical joke” or “a misogynist prank.” She conceives of sexual assault as a joke that only one party is in on. “Using humour to fashion my prose would be tasteless, but not more tasteless than rape itself.” She reflects on the ways in which humour can provide a necessary distance between survivors and their experiences due to its ability to “anesthetize,” while paradoxically allowing survivors to approach and address what happened to them. “Those of us who think about [rape] a lot need to get near it,” she writes. “How close do I want to creep?”

“Of course, ‘creep,’ in addition to being a noun, is also a verb—it is what fog does, and fog is an excellent shield behind which abusers can act with impunity.”

Of course, “creep,” in addition to being a noun, is also a verb—it is what fog does, and fog is an excellent shield behind which abusers can act with impunity. In the harrowing titular essay, which Gurba effectively saves for last, like a massive wave hitting the shore after building for the duration of the book, she forensically dissects a three-year-long physically, sexually and emotionally abusive and coercive relationship that she survived. During this relationship, she continued to teach high school and also wrote Mean as a way to wedge open some space for herself. She describes the emotional fog that enveloped her during that period, which she only identified afterward. She recalls the fog that would creep through the Santa Maria Valley, where she grew up, billowing and obscuring, making driving dangerous and also providing convenient visual protection for her early queer experiences with a neighbourhood girl. The fog of domestic violence held no such stealthy queer excitement.

Gurba’s forensic approach to laying out the various escalations of violence and coercion that she experienced with Q, her partner at the time, serves as a generous reminder that domestic abuse can happen to anyone. In expressing surprise that a smart, educated queer woman can find herself trapped in an abusive relationship with a man, she observes how we effectively draw a line between “battered women and everybody else.” This notion that “strong” or “smart” people can’t be drawn into abusive relationships compounds the shame that people feel within these situations, which makes it all the harder to leave them. Q used Gurba’s bisexuality against her, accusing her of only objecting to his increasing physical abuse due to not understanding what it’s like to date cis men; throughout early adulthood until her late 30s, she had been married to a woman, and had only dated other queers. This, and other insidious tactics, steeped in misogyny and queerphobia, were how Gurba’s partner “lured [her] into the fog.”

The first object he used in violence against her was a pillow over her face—soft, swaddling and potentially deadly. She describes feeling confused by this choice of object, how “Q used something soft to harm.” After he lets Gurba go, he begins to whistle. “He was acting as if he hadn’t done anything weird, like asphyxiating a girlfriend was a normal thing to do.” Gurba also describes how Q would urge her to read him the glowing reviews of Mean, acting friendly and supportive, then suddenly turning violent once she was done. “When he feels small, someone must pay. If I make him feel small, he charges extra.” Being a queer woman and a celebrated writer did not protect Gurba from abuse; instead, these personal attributes deeply informed Q’s coercive tactics.

After she leaves him for good, a terrifying ordeal in itself, Gurba gets a restraining order against him, and asks the HR department at their shared workplace to make sure he doesn’t work around women or kids anymore. She is treated with suspicion and disdain: Q is well liked, she is told, and it’s hard to believe any of her allegations against him. Thus, she writes, creeps may appear to act alone and often in private, but they are in fact heavily supported by power structures that ignore or even encourage their violence: “Embedded within these systems of family, friendship, and community, these creepy men may appear harmless, their evil obscured by a benign collective presence, a fog of sorts. This softness swaddles and protects them. This fog abets.”

In her recently published “A year in reading” piece for The Millions, Gurba lists two books that she says were instrumental in helping her understand her experience of domestic abuse. People who batter their partners are not complicated, she writes: “By controlling women, batterers enrich themselves. They steal our money, time and labour. Now that I’m free, I’m able to devote my time and labour to writing books that I hope help set others free.” Creep is already a discerning, unflinching, loving—and yes, funny—contribution to the project of freedom, for women and queers, for survivors of rape and abuse, for Mexican-Americans and other racialized and Indigenous people living in white supremacist settler-colonial states. By illuminating and enumerating instances of abuse—of intimate partners, of incarcerated people, of positions of power steeped in Eurocentric worldviews—Gurba’s essays begin to dispel the fog that swaddles so many North American institutions and interpersonal relationships.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra