“I always hated ‘realistic fiction,’” announces the narrator of “Realistic Fiction,” the eponymous opening story in Anton Solomonik’s new collection. The narrator models his masculinity after his father, who reads police and spy novels; stories in which things happen, men take action and participate in global affairs. These novels are preferable, in the narrator’s view, to “slice-of-life writing in which … no one does anything, there’s no plot, no conflict.” After using money from his father to start hormone therapy, the narrator gets into weightlifting and goes on a date with a woman, even though he’s pretty sure that he is gay.

During the date, the woman’s vulnerability and disappointment when he exhibits a lack of interest end up propelling him into a new gendered dynamic in which he experiences his own masculinity in response to the woman’s “feminine instinct to please”—an instinct he knows well and strives to shed. His date’s self-consciousness, he realizes, means that he is no longer under observation. He becomes a sort of object instead of a person with “ridiculous, feminine emotional needs.” He relaxes, and the two of them have sex. Afterward, the narrator can, for the first time, imagine himself becoming his father.

The story ends here, winking at the fact that the reader probably expects more to happen after this important psychological revelation: “If this were a story, here is where the plot would be.” A story that undermines itself by presenting a strong case for its illegitimacy is a fitting opener for Solomonik’s collection. His protagonists, most of whom are trans men, obsess and fixate on both ontological and practical questions: How can one determine the reality of the world and its objects? How can one seize control of one’s reality? Is reality masculine? Is it possible to get a job in an open pit boron mine with no relevant work experience?

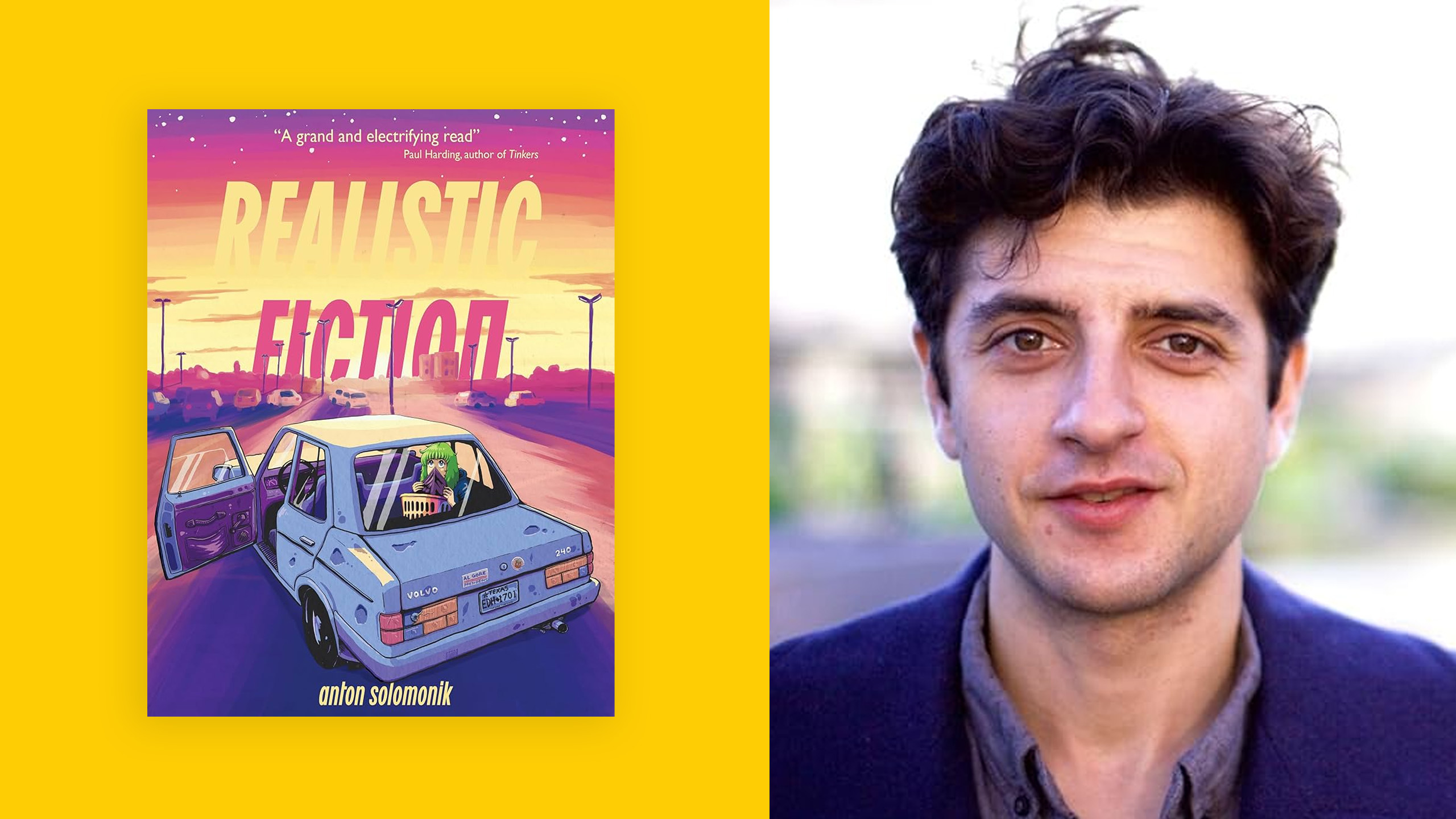

This is Anton Solomonik’s first book, though he has been active in the trans literary scene for some time; he and Jeanne Thornton co-host the World Transsexual Forum, a well-known open mic for trans and gender nonconforming writers and artists in New York City. Like Thornton, whose novel A/S/L comes out the same week as Realistic Fiction, Solomonik writes stories of trans life that upend mainstream notions of transness as a linear trajectory from one fixed gender to another. He refutes the comforting idea that all that’s needed for the well-being of trans people is acceptance by the straight world. His narrators, whether or not they understand their own transness yet, are marked by confusion, contradiction, selfishness, vulnerability and a vigour that is both off-putting and endearing. In the collection’s eleven stories, characters move to Boron, California; discover that finding a partner based solely on a shared worship of Ayn Rand might be ill-advised; run a grassroots campaign for Congress despite having no social networks; and briefly encounter gender euphoria by cross-dressing as the opposite (trans) gender. Throughout, awkwardness and alienation abound, transmitted to the reader by Solomonik’s blunt and often hilarious prose.

A question resounds through these stories: How should a man behave? The protagonists of Realistic Fiction often seek the answer to this question by studying the lives of historical and fictional male figures. In “Porn,” Lex carries around a copy of Rousseau’s Confessions and evaluates the appearance of men with facial hair, wondering if, under the beards, which Lex finds stupid, they might have classical European features like the eighteenth-century luminary. In “Complicity,” the titular character is fascinated by the homosocial relationship between two clergymen in the austere confines of Willa Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop. Complicity is impressed by the men’s ascetic commitment to reflecting on the flawed state of humanity, which to her is a positive contrast to her English teacher’s “alienating feminine energy.”

In “Moving to Boron,” Wolfscum, our narrator, and his friend Punk Skunk are obsessed with Sol Invictus, an anime about the life of Alexander the Great. Wolfscum persuades Punk Skunk that they should move to Boron, California, the site of the world’s largest open pit boron mine, in order to live in what he imagines to be a harsh and pitiless landscape. He recalls how Alexander the Great laid waste to Thebes at the start of his military career: “Sometimes you gotta put your own shit to the sword.” Throughout the story, Wolfscum chases a concept of masculinity that he has trouble embodying: he tries to get a job working in the mine, and when he is rebuffed for his utter lack of experience, he takes an unpaid position at the visitor’s centre, sorting tools, which he also proves unable to do. He analyzes and tries to emulate the men around him. On the one hand, he observes Punk Skunk, whose “unforced, informal manner of speech seemed to inspire confidence in people, despite the frequent incoherence of what he said.” On the other hand, his supervisor at the visitor’s centre impresses Wolfscum with his more rugged version of masculinity: “He moved so quickly. I wondered if I would ever be able to achieve the same mastery over space and objects.”

Seeking mastery over the material world is a recurring preoccupation for Solomonik’s characters. In “The Meaningful Ex,” the protagonist is impressed by a man he meets at a gnostic mass, who has “the conspicuously straight posture of someone who wanted to assert his will over material reality”—a posture that the protagonist strives to maintain in public. In “The Meeting of the Minds,” the narrator goes on a disappointing date with a guy who, like the narrator, loves Ayn Rand. “Sex was the logical outcome of two characters’ metaphysical compatibility,” according to Rand’s writings, but the narrator discovers otherwise. Geoff, the date, presents himself as the ultra-rational Randian man, which the narrator admires and seeks to embody as well; yet somehow, as the two discuss their shared love of Rand’s objectivism, the narrator becomes increasingly uncertain, and therefore, in their mind, feminized in the face of Geoff’s overbearing certainty. The unspoken problem for the narrator might be that transness is incompatible with objectivism. “You can’t say a car is a chair,” asserts Geoff; meanwhile, the narrator wonders whether the qualities of objects exist in the mind or whether the objects have qualities in and of themselves—what makes an object what it is? The unspoken question: What makes a man a man or a woman a woman? Can these categories ever be breached? Things are feeling dire for the narrator when, in a rush of reclaimed agency, they tell Geoff that he doesn’t exist, before kicking him in the shin and running away. The narrator proceeds to buy a Popsicle, which, though it looks as if it’s made of red meat, is actually “frozen chunks of real berries.” Reality, thankfully, is not so static after all.

Solomonik’s protagonists constantly question themselves, and yet they undertake determined actions in their own lives. These actions, often driven by prescribed notions of masculinity, do little to reduce the characters’ alienation from themselves and others; and yet, sometimes the humiliation of public alienation is the catalyst for forging new realities. In “The Meaningful Ex,” Origen, the trans son of Russian immigrants who has recently started asking his lover to make him eat dog food, wonders whether humiliation itself might be the path to a new reality in which humiliation does not matter. In “Cassandra,” Ashton, a trans man who is trying to run a progressive grassroots campaign for Congress, engages in an evening-long antagonistic flirtation with his best friend’s unnamed girlfriend, who is also trans. They end up encouraging and mirroring each other: the girlfriend decides to go to Ashton’s political event cross-dressed as a trans man, and Ashton follows suit, donning feminine drag and adopting “Cassandra” as a persona. Appraising them both in the mirror, the girlfriend pronounces that they look like “a fucking hot pair of transsexuals!” Out at a bar, Ashton/Cassandra finds that making his/her transness hyper-visible, rather than trying to pass, feels humiliating and therefore oddly freeing, a “cathartic outward expression of what was normally hidden in my relations with others—that desperate, shamefully feminine need for attention.” This need for attention is what initially bothered Ashton about his companion, but now he finds it attractive and embodies it as well, and the two end up gleefully hooking up in the bar bathroom before parting ways. The euphoria of having transcended the bounds of humiliation and the confines of (trans)gender is fleeting, but it was there. It was real.

Though the characters in Realistic Fiction are often hapless, at odds with the structures and rituals of the world they live in, they are also active architects of their fates. Solomonik’s stories are staunchly pro-discomfort. They brim with awkward encounters and ugly feelings, and they show us that discomfort can be a way to access a sense of freedom or connection with others. Interpersonal tension, and worrying about what others think of you, is “how you know you are really capable of caring and feeling,” as the narrator of “The Meaningful Ex” puts it. By rushing headlong into inadvisable, often baffling decisions, and refusing the confines of normalcy, the characters in Realistic Fiction remake the mundane world into one that is still realistic—because of and not in spite of its undeniable strangeness and endless changeability. Solomonik’s trans stories are not a plea for acceptance—they are bold and bizarre and tender and confrontational. They might make you squirm and will definitely make you laugh. His characters are sometimes annoying, often misguided and always compelling. In asking us to lean into the chaos and absurdity that exist beneath the veneer of normalcy, his realistic fiction turns everything inside out, even itself.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra