The University of Rochester is home to one of the largest collections of AIDS posters in the world. Donated by physician and medical historian Edward C. Atwater, who died in 2019, the collection currently encompasses more than 8,000 posters spanning 40 years. Ahead of an in-person exhibition next spring at the Memorial Art Gallery, the Rochester Institute of Technology Press (RIT Press) recently published Up Against the Wall: Art, Activism, and the AIDS Poster, edited by Donald Albrecht and Jessica Lacher-Feldman. The book dives deep into the collection with reproductions of 171 posters accompanied by a wide range of essays from authors like Anthony Fauci, Alex McClelland and Kyle Croft. Some essays are longer overviews of subjects, like the history of AIDS or how the collection came about, while others are shorter pieces that speak to a particular poster (two of those are reprinted below, along with this excerpt from “Worlds of Signification,” an article on the uniqueness of posters as sites of outrage, action and education).

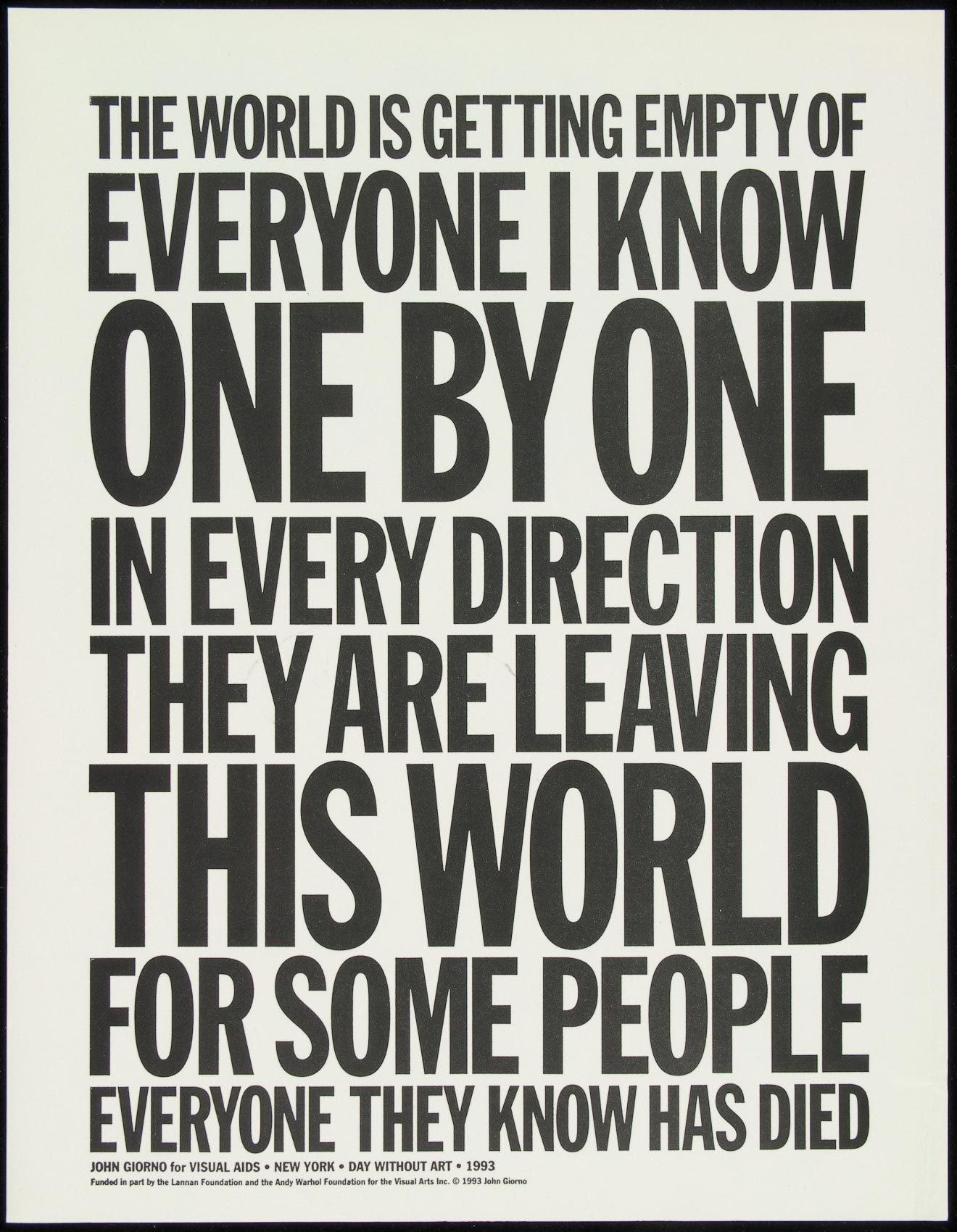

We all live with AIDS. Some of us live with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, in our bodies. We face attempts to control and surveil our actions and behaviours. We sometimes receive care and treatment for how the disease affects us. Some of us live with AIDS outside our bodies. We experience the cultural and sexual effects of AIDS, whether that includes how we navigate healthcare systems or conceive of and negotiate notions of risk. While both groups can, and sometimes do, choose to ignore AIDS, only people who believe they are immune can do so with impunity. The AIDS epidemic has affected, and continues to affect, everyone on the planet. No one has been immune to the seismic social, medical, and political impact of AIDS during the past 40 years. We all live with AIDS. We can all fight against AIDS.

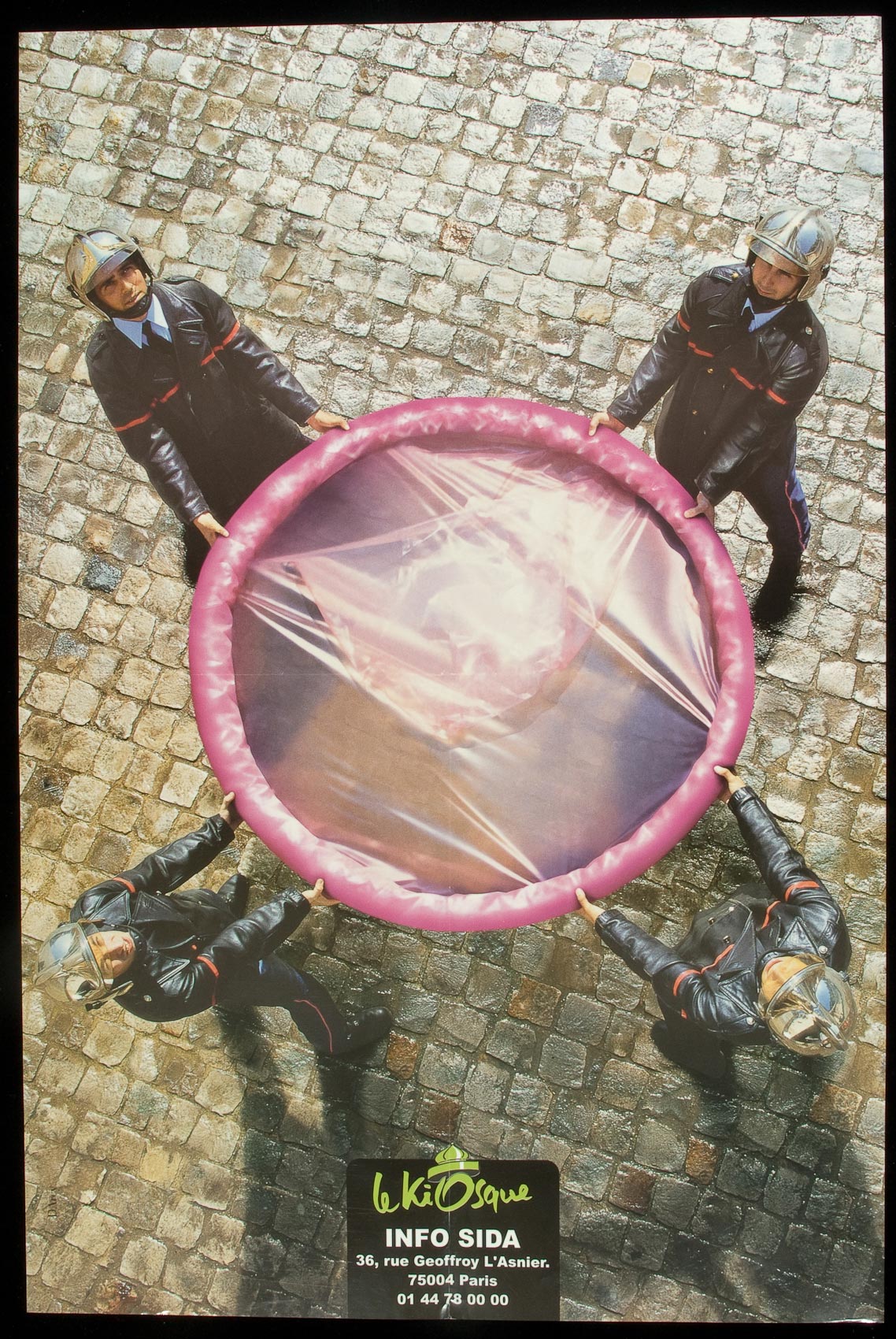

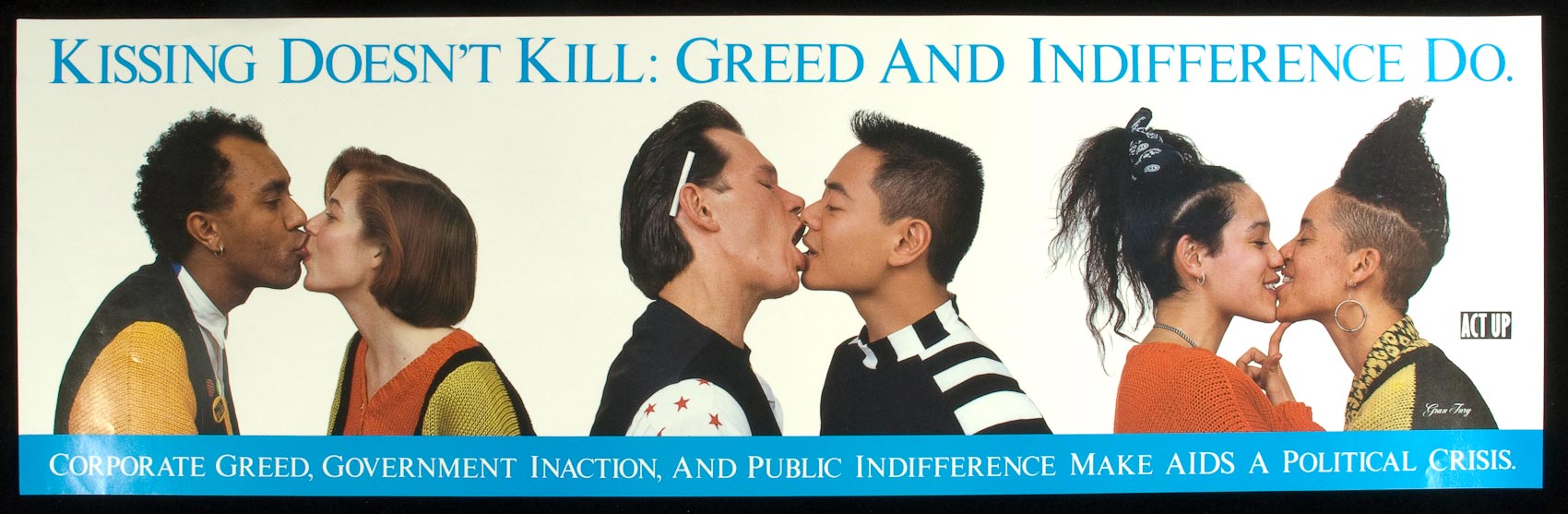

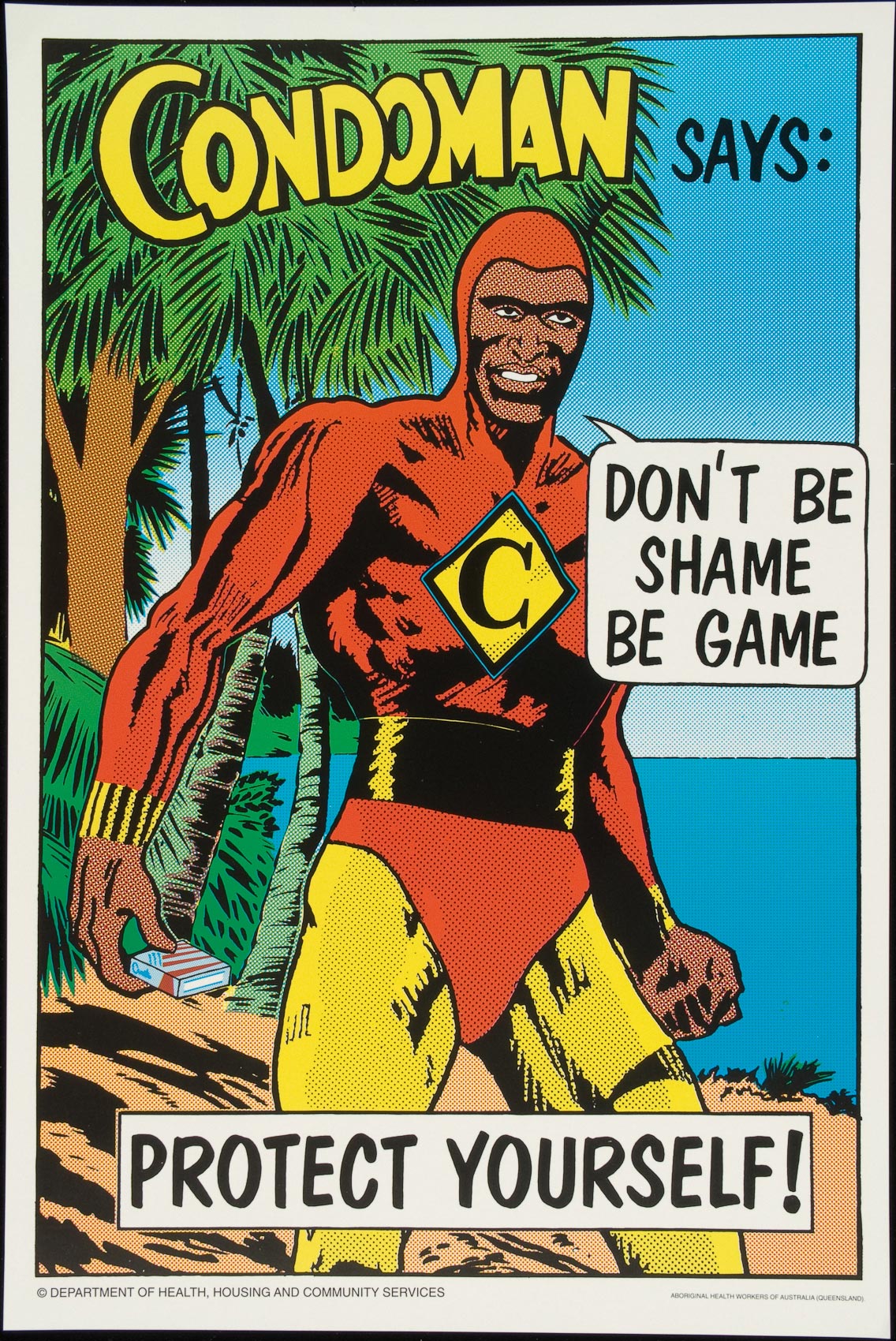

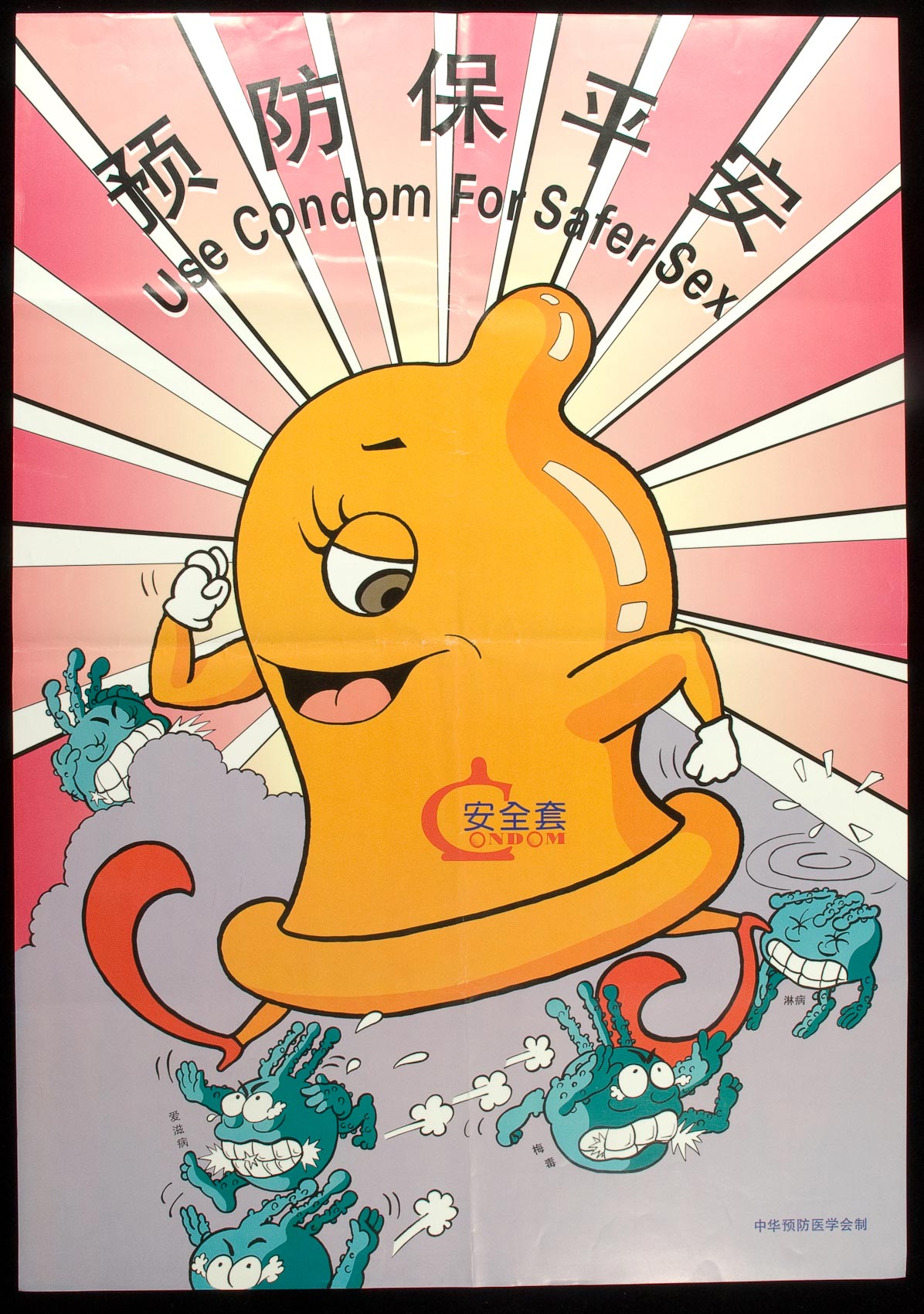

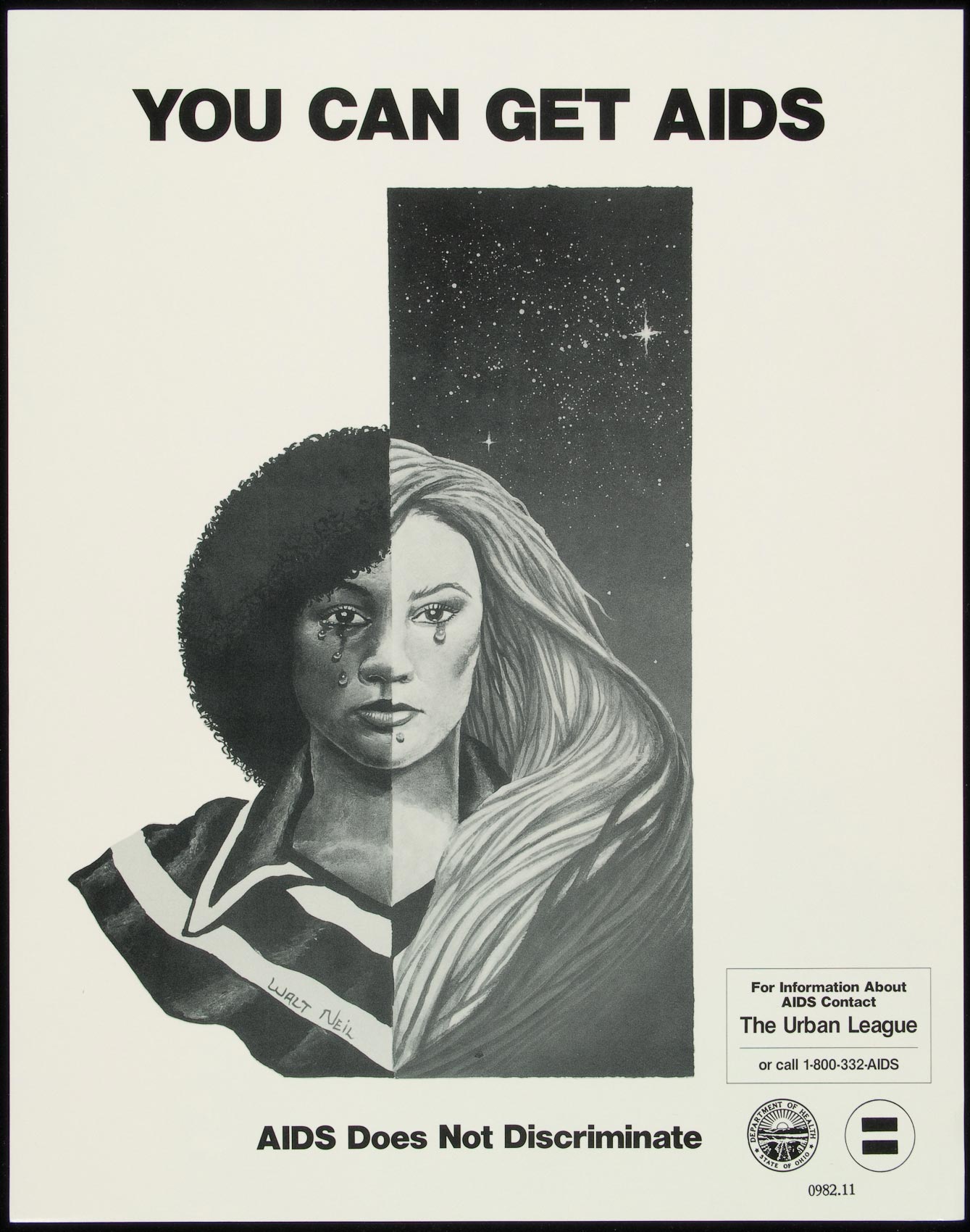

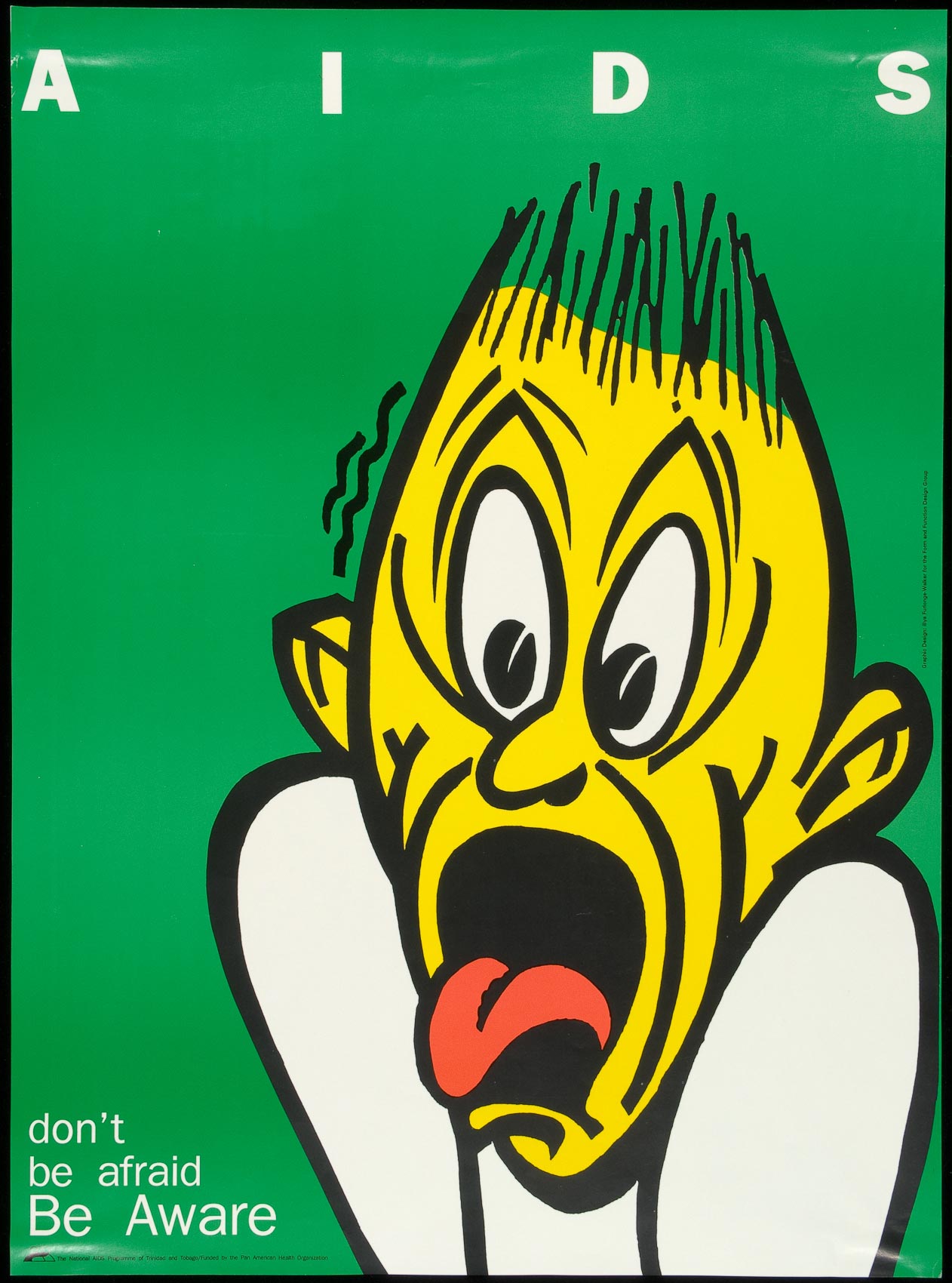

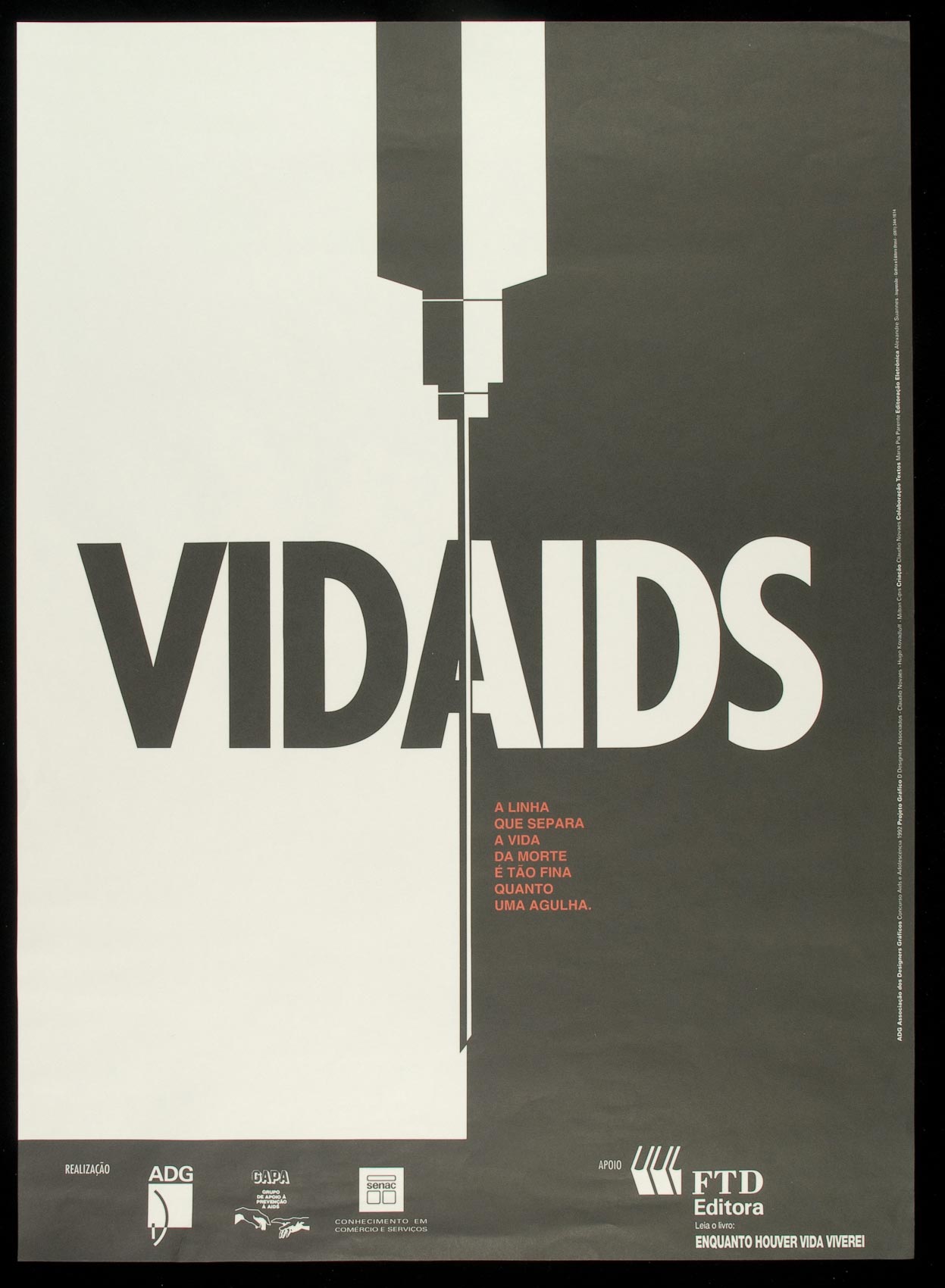

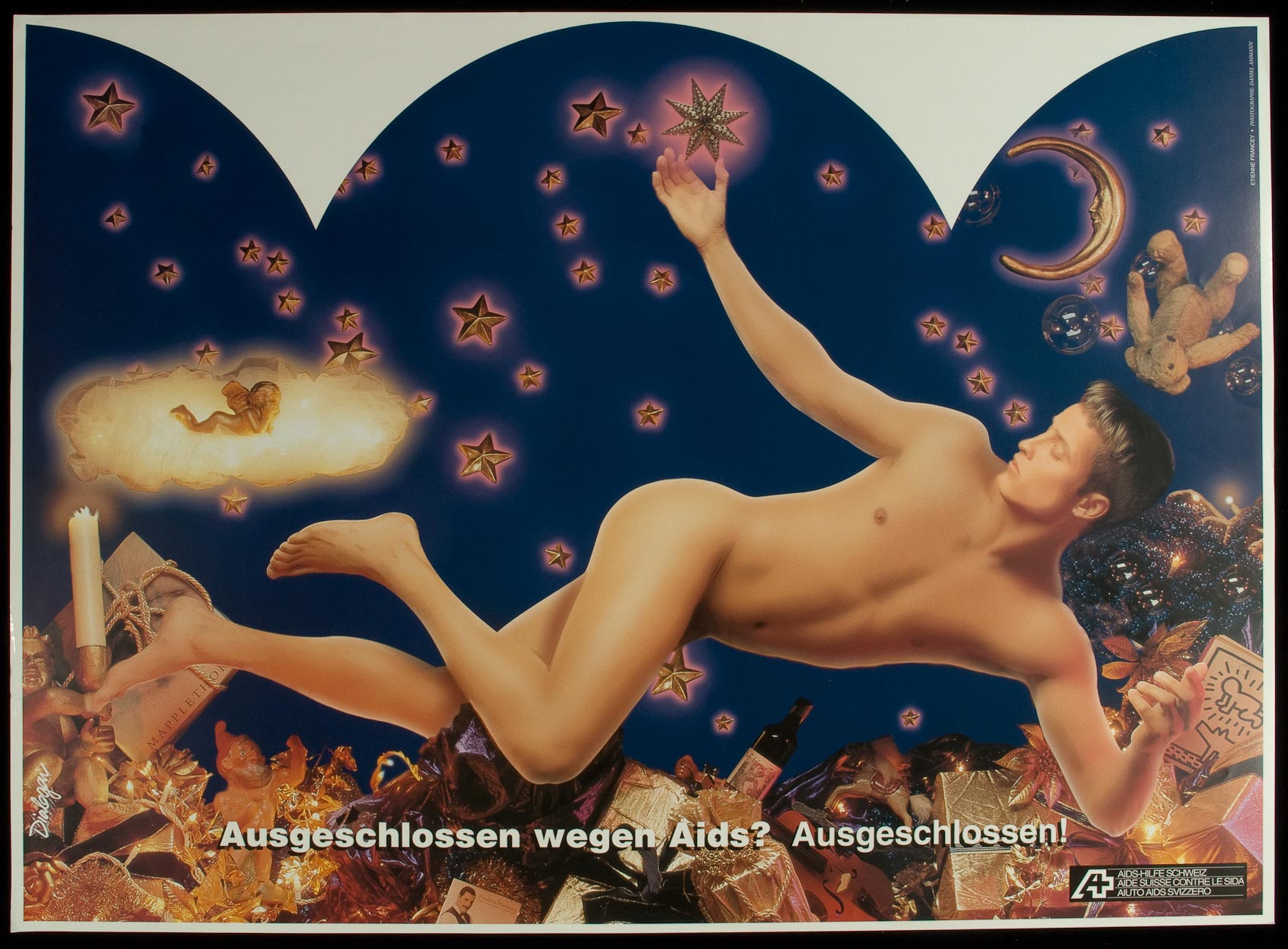

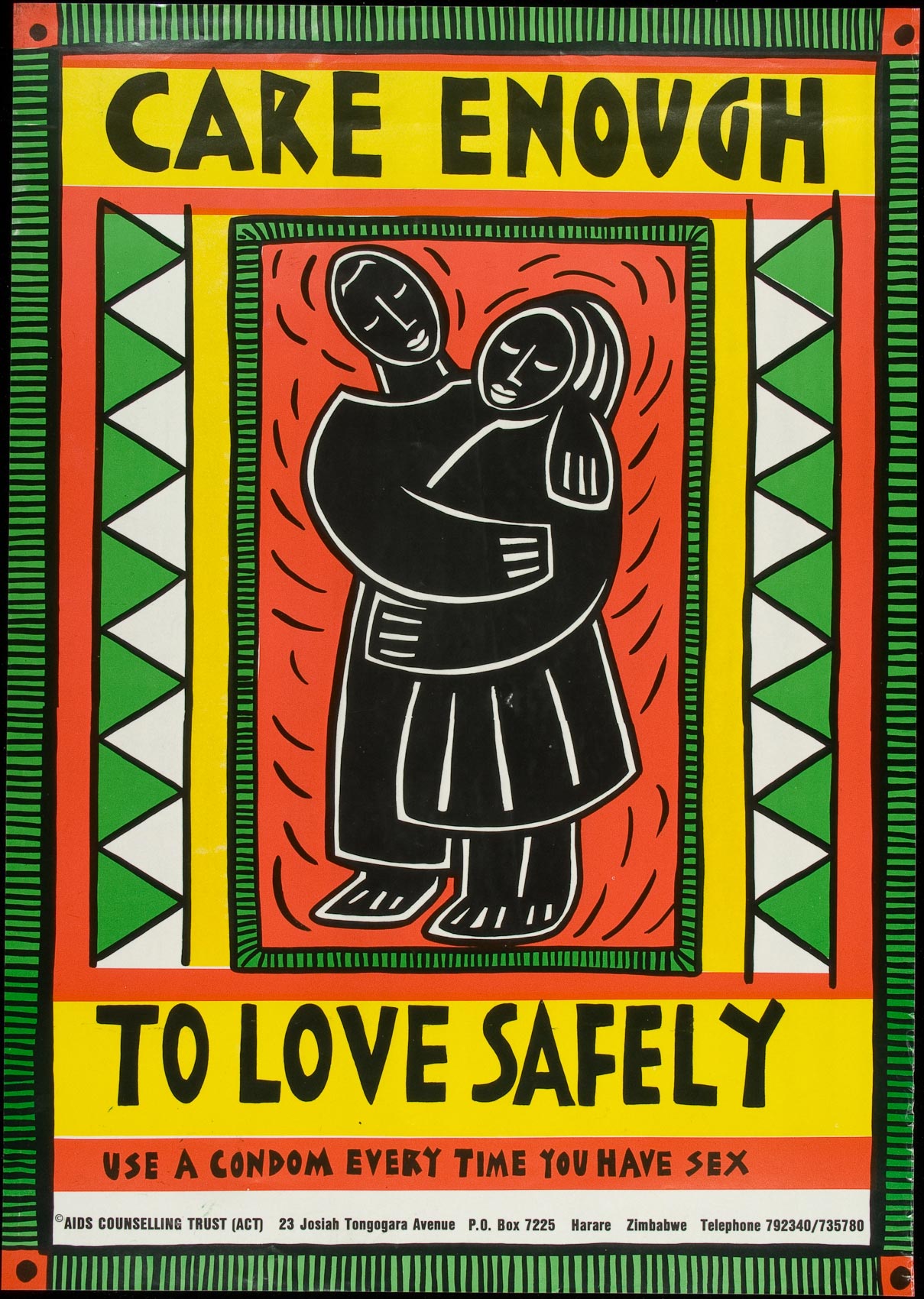

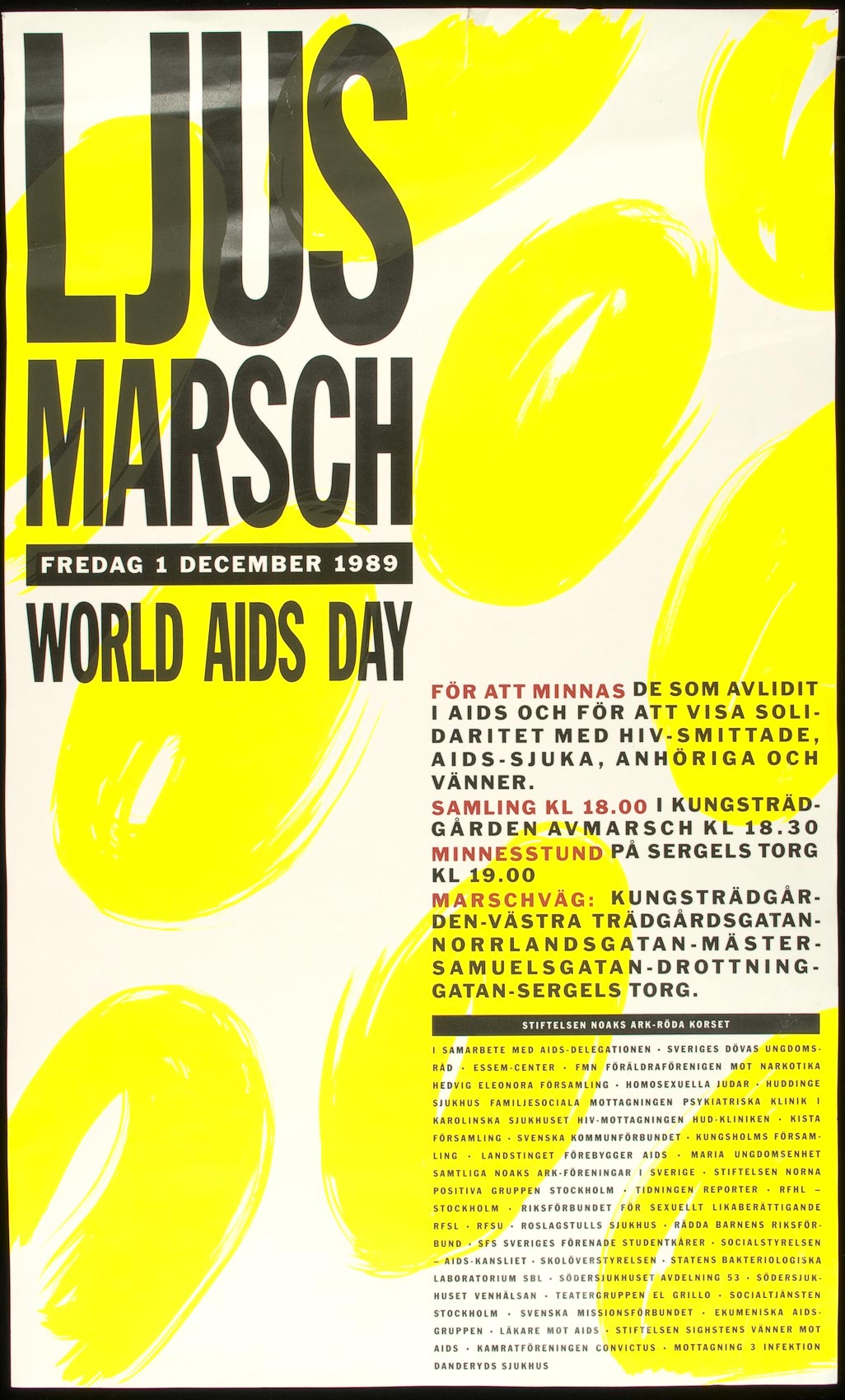

The images presented in Up Against the Wall are from a collection of more than 8,000 posters and related ephemera held at the University of Rochester. The posters are a visual record of the complex ubiquity of AIDS. They produce a kaleidoscope of visual information—moral instructions, prescriptions for imagined and real behaviours, calls to action, identity-making metaphors, cultural markers, and more. As individuals, each poster attempts to describe some aspect of an impossibly sprawling subject and provides a unique and discrete constellation of ideas, metaphors, and cultural encodings. Each poster produces meaning, whether by calling forth new patterns of individual behaviours in the form of “safer sex” or no sex at all, naming “the state” as a key actor in a process of making citizens healthy, generating new metaphors to experience or comprehend AIDS, or imploring direct action and protest in response to AIDS.

Many of these posters were made in the 1980s and ’90s, just before the Internet fundamentally changed how we access and understand images. They were designed as physical objects made for physical spaces—on the walls of bars, health clinics, and doctors’ offices, and in public spaces such as urban streetscapes, on mass transit, and even pasted on scaffolding marked “post no bills.” They were meant to be seen and interpreted in person, at a specific place and time.

Just as no two posters are identical, the AIDS epidemic is multifarious. Studying this collection confirms what cultural theorist Paula Treichler meant when she described AIDS as an “epidemic of signification.” In coining this phrase—one that has been taken up in most subsequent historical texts on AIDS—Treichler wanted us to see that “the AIDS epidemic—with its genuine potential for global devastation—is simultaneously an epidemic of a transmissible lethal disease and an epidemic of meaning or signification.” She called out the “chaotic assemblage of understandings of AIDS,” all of which are attempts at “making sense” of it. By now it is practically axiomatic that AIDS is a social construct in which meaning is constantly produced and reproduced. Each poster in this collection creates its own world of signification.

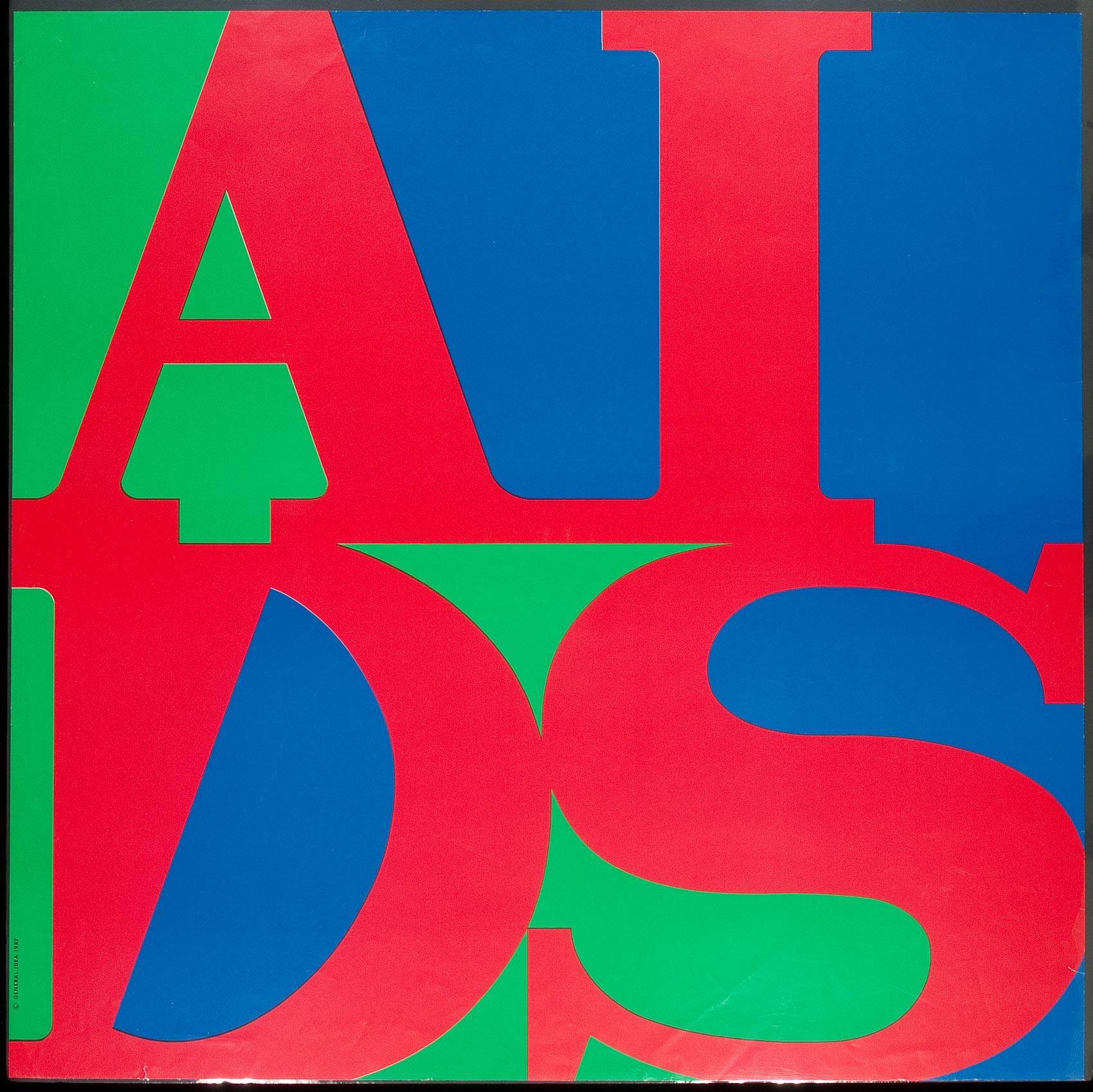

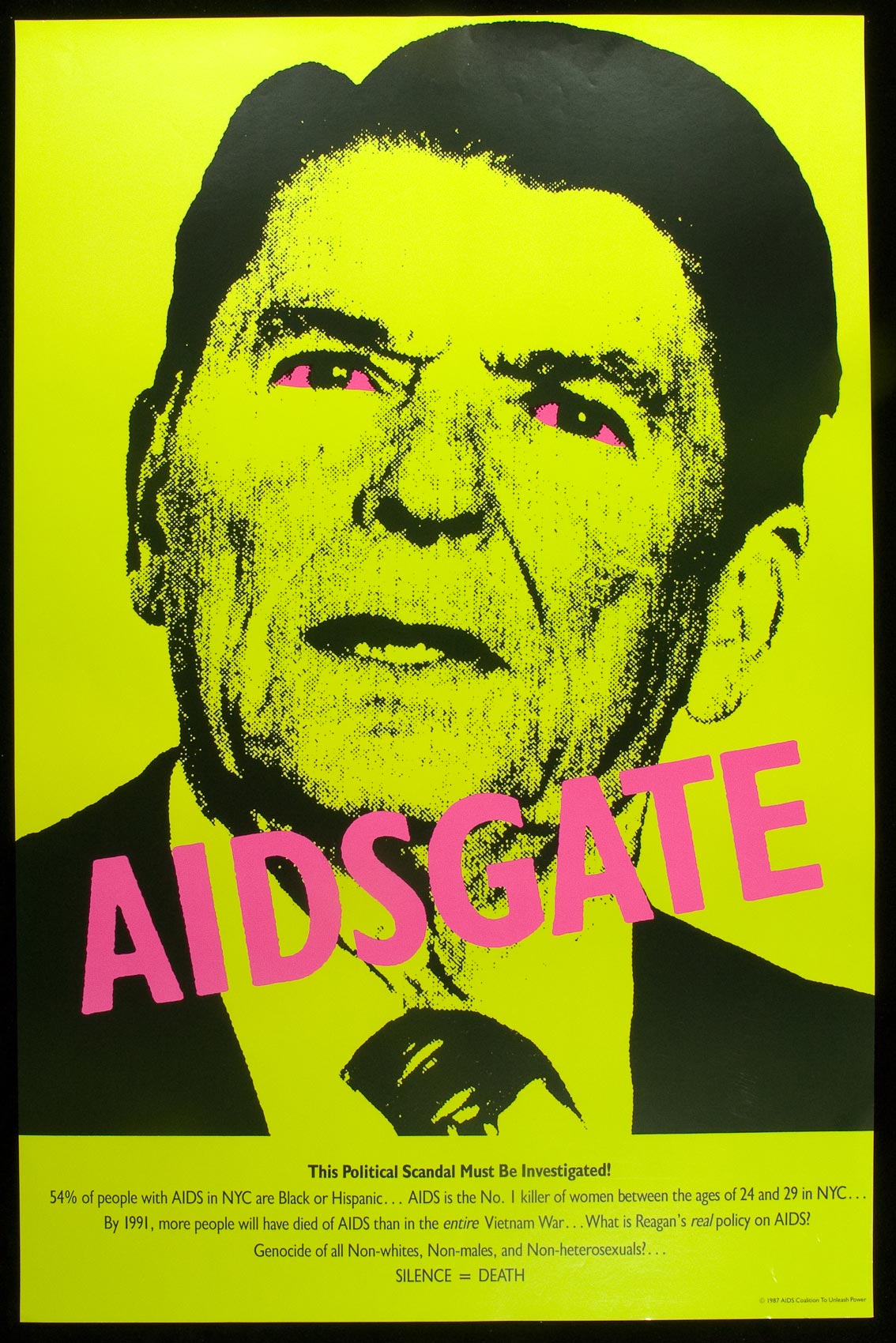

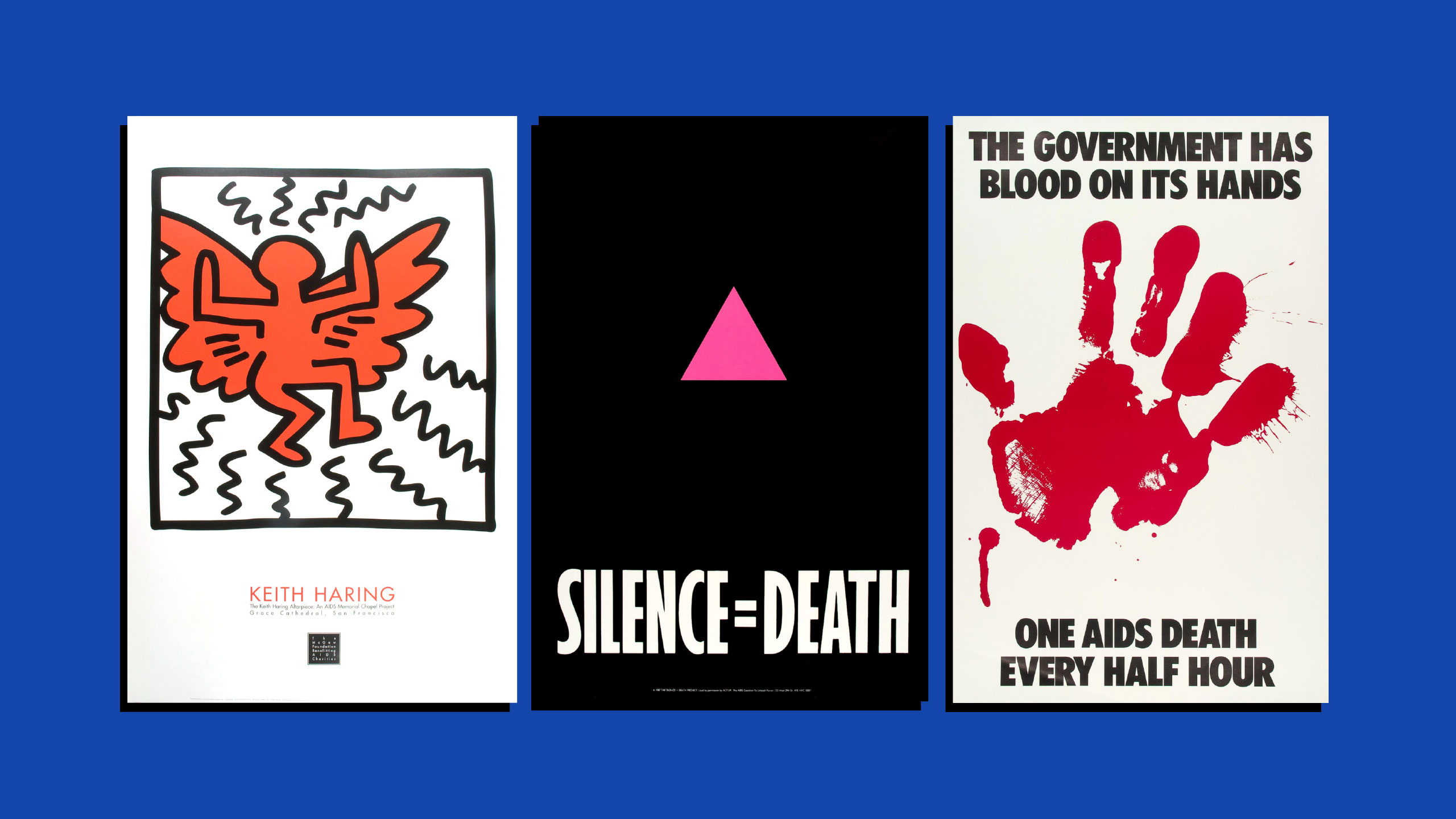

The proliferation of graphic works arising in response to the AIDS crisis marked the visual landscape with a new four-letter word that would come to define a generation “united in anger,” fortified through their resistance to the very extremes of stigma, and in a love deep enough to give care to those at the very limits of life. Replacing Robert Indiana’s iconic artwork LOVE, artists Felix Partz, Jorge Zontal, and AA Bronson, who from 1969 to 1994 comprised the Canadian collective General Idea, demanded a widespread—indeed viral—regard for AIDS in a political climate haunted by a deadly, infuriating silence. The U.S. saw AIDS made infinitely reproducible in bold text filling the volumetric void left by the refusal on the part of the Reagan administration to speak its name.

Then came AIDSGATE. Published in 1987, a scowling Reagan appears in halftone, leering from an acid yellow page, the whites of his eyes burning pink. The striking neologism is stamped across his neck in the same hot pink used for the inverted pink triangle the year before when the proclamation “Silence = Death” was made by a newly formed collective of the same name. The Silence = Death Collective went on to create the “AIDSGATE” poster, which, distributed by then-yearling ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), effectively branded Reagan’s violently negligent presidency. Appearing the year in which Reagan made his first major speech on AIDS, the work remains an iconic touchstone for understanding the impact of the U.S. government’s silence and subsequent outright refusal to take action at the time of the crisis. Coming five years after the acronym AIDS was first acknowledged and published in the press, Reagan’s first-ever speech on AIDS came with the announcement that the government would not support AIDS education efforts. In the wake of this announcement, ACT UP’s poster asks, “What is Reagan’s real policy on AIDS? Genocide of all Non-whites, Non-males, and Non-heterosexuals?”

—Johnny Forever Nawracaj is a non-binary, Polish born multidisciplinary artist who holds an MFA from Roski School of Art and Design at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles as well as an MA in art history from Concordia University in Montreal

The image, “Final Moments” (1990), was taken by Therese Frare the spring that David Kirby died of complications related to AIDS. Months after, the picture was published in LIFE magazine, iconically retitled “The Face of AIDS.” Two years later, it was used for what became an infamous Benetton clothing ad, even more powerfully titled “La Pieta.” The photograph provides an important and familiar narrative—a frail young man, dying needlessly before his time. And in that, the picture also contains details and absences that speak to stories and dynamics of the ongoing AIDS crisis largely untold, teetering on the precipice of being lost. The hand on David’s wrist belongs to his caregiver, Peta, who, the day the photo was taken, invited Therese, a photography student at the time doing a project on AIDS, to follow as Peta did rounds at the hospice. Therese stayed in the hallway as Peta went in to check on David, a friend, who was near his final days. Therese had met David once before, and he had given her his permission to be photographed. As Peta visited with David, David’s mother invited Therese into the room, asking her to take photos of what could be their last moments all together. On Therese’s contact sheets from that day, Peta’s whole body can be seen: tall, with long hair pulled back, wearing a black leather jacket. In Peta we meet a caregiver from the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation living with HIV, who, as Therese recalls, “rode the line between genders.” After David died, the Kirbys made a commitment to care for Peta as death approached, and Therese continued to photograph. Let Peta’s wrist—and spirit—encourage viewers to look beyond the poster frame, searching for the stories untold, and the context needed to better understand the history and ongoingness of HIV/AIDS.

—Theodore (Ted) Kerr is a New York-based writer and a founding member of the collective What Would an HIV Doula Do?

All images courtesy of RIT Press.

To mark World AIDS Day on Dec. 1, the University of Rochester is hosting an in-person event at the Memorial Art Gallery featuring a digital display from the AIDS poster collection and a concert (livestreamed beginning at 6:30 p.m. ET).

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra