Administrators in an Iowa school district made headlines last fall after revealing that they’d employed ChatGPT to identify and remove books from their school libraries. Their actions were a result of a new state law “prohibiting instruction related to gender identity and sexual orientation in school districts, charter schools and innovation zone schools in kindergarten through grade six.” In December, a U.S. federal judge ruled that the law, in all of its ambiguity, could not be enforced. But questions surrounding not only the law, but the artificial intelligence-aided censorship that resulted from it, continue to proliferate.

In an interview with Wired, the Iowan school administrator in question noted that she turned to ChatGPT in large part out of frustration. When it comes to complying with the law and banning books, she said, “I don’t want to do it.” ChatGPT seems to have offered her, like many of us, a shortcut, a means to plow through tasks that are otherwise too mundane, time-consuming or confusing. But what are the costs of these shortcuts?

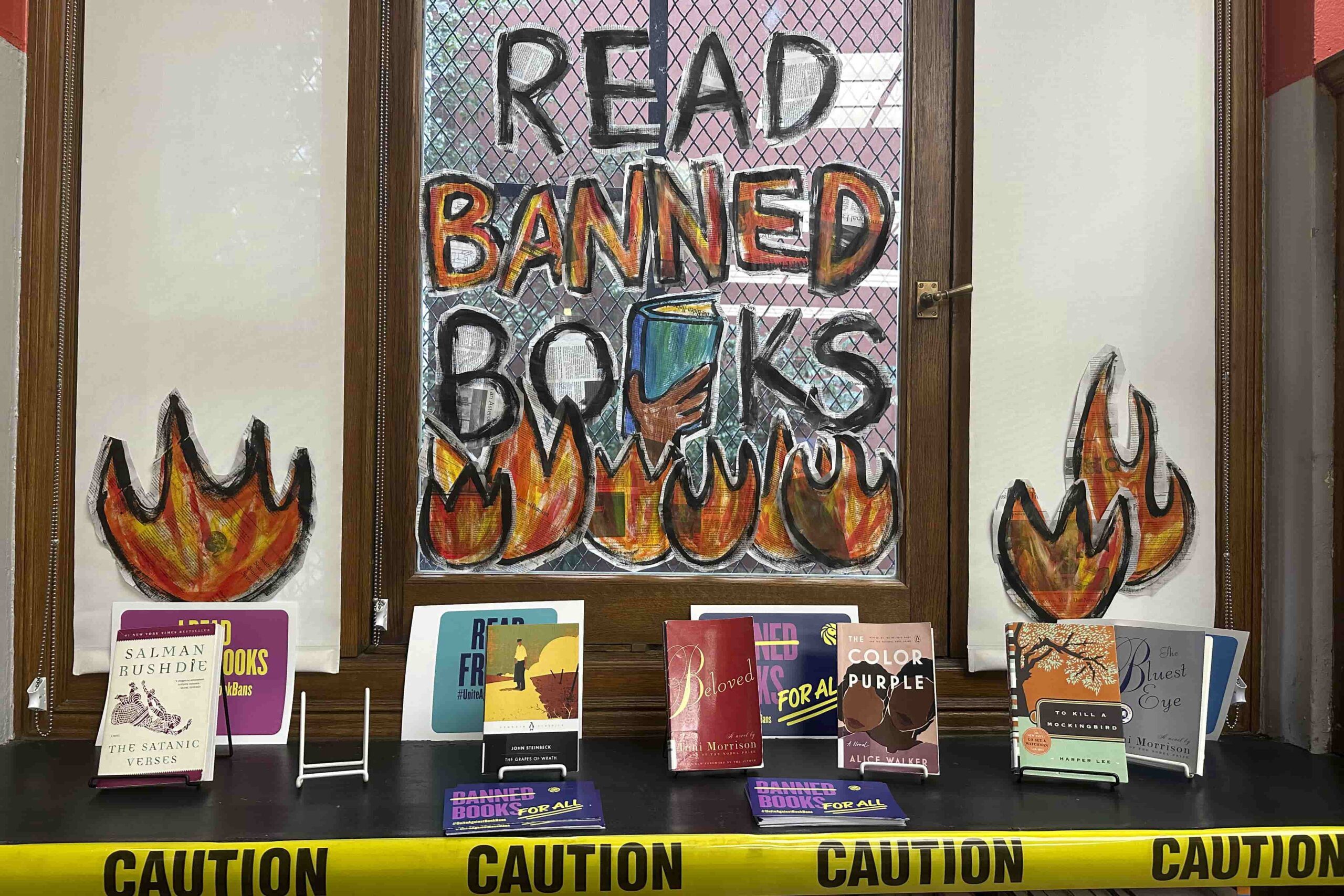

Ongoing book challenges, predominantly directed at books about and by queer folks and people of colour, have become a staple of our modern lives, but their conflation with AI presents a new cause for concern. While few instances have garnered the same amount of attention and open discussion as that of the Iowa school district, many of the recent and bizarre censorship cases lead one to ponder just how prevalent tools like ChatGPT have become in the act of removing books from our libraries. Earlier this year, for instance, a Florida school district pulled 1,600 texts from their schools, including five different dictionaries, as well as a number of encyclopedias and even The Guinness Book of World Records. One almost hopes that this was a result of poorly automated efforts.

But not really.

Modes of automated censorship have a long history of disproportionately affecting queer and gender nonconforming people, a history that digital media scholar Alexander Monea has expertly traced out in his book The Digital Closet. As he observes, “Nearly every major internet platform today engages in systematic overblocking of sexual expression, which by default reinforces heteronormativity.” The case studies that Monea draws on are seemingly endless. In 2017, YouTube filtered a range of LGBTQ2S+ vloggers into a new “restricted mode” after marking their content as “inappropriate.” Social media influencer Tyler Oakley, for instance, tweeted out that he was confused over why a video he’d uploaded—“8 Black LGBTQ+ Trailblazers Who Inspire Me”—was censored by these new guidelines. Similarly, back in 2011, Facebook censored a photo of a gay kiss, drawing even more attention to this issue of overblocking queer content.

What this last instance shows is another concern that Monea emphasizes in his work. More recent cases of automated censorship have a tendency to obscure the all-too human decision-makers operating behind the scenes. Over-filtering algorithms don’t begin in a vacuum; they always come from somewhere—that is to say, from someone. Monea refers to the actual people who often filter through internet content as “human algorithms,” but the human labour at work in more traditional forms of decision-making serves as a reminder that all forms of censorship—whether automated or not—are embedded with human biases and perspectives that may be at odds with those on the other end of censorship.

But the moral code behind ChatGPT and other large language models remains opaque. As users, we often lack the ability to crack open these tools and to understand the contexts of their generated responses. Then again, understanding context is one of the things that these tools tend to struggle with as well. It’s a shortcoming of our digital mediums more broadly. In the case of the Iowa administrators, they mention cross-referencing the books that ChatGPT suggested banning with another online platform: BookLooks.org. This site, designed to provide brief summaries of a book’s “objectionable content” is similarly opaque and lacking in context. The creators of the site regard themselves simply as “concerned parents,” but their tendency to flag elements like “alternate gender ideologies” seems to me a greater cause for concern.

The creators’ objections to various books also lack any useful context. Sure, the site offers a word count of terms that its creators have found questionable, but they haven’t provided any information about why these terms were used or how they fit into the larger narrative of the book. More importantly, they haven’t even attempted to address why the book might be important enough to merit sitting with or sifting through “objectionable content” to begin with. According to the site, George M. Johnson’s frequently challenged All Boys Aren’t Blue raises concerns over language and profanity, using the word “shit” 11 times, for example. But while the site gives me this keyword count, nowhere does it reference why this term was used or in what context. Words have different connotations depending on the audience, the speaker and the broader rhetorical situation.

And despite the site’s many “concerns” that BookLooks.org raises, it never acknowledges what Johnson’s work actually is—a sweeping memoir that manages to be beautiful, painful and resiliently joyful all at the same time. The site never mentions this, nor that the author’s reflections as a young, queer Black man affords readers an engaging and complex narrative of the kind that is often underrepresented by our contemporary media offerings, which (it so happens) is a concern that I care about.

BookLooks.org is by no means an authority I wish to follow. But ChatGPT, in its latest iterations, could already be drawing on the site as part of its data intake. Using AI tools for something like understanding a book’s content, then, adds additional levels of noise and abstraction that might save time in the short term, but they’ll also compress and leave out all sorts of nuance, detail and meaning. And when it comes to the richness of literature and concerns around representation, I’m generally not looking for compression.

Monea highlights this same idea in his work. Real life is complicated. Noting this, he writes, “Critical thought requires us to learn how to navigate these grey areas, and the development of this capacity takes many years of practice, online or off. Overbroad filters stunt this development, blocking access to everything from legitimate nonsexual speech to hard-core pornography and all the grey areas in between.”

It’s the complex reality of these grey areas that we risk compressing, flattening and losing when we rely too greatly on AI. And, without overstating the issue, it’s our own ability to think for ourselves that we risk losing when we depend too much on any algorithm, whether human or AI.

Over 30 years ago, Sasha Alyson, the founder of the queer publishing house Alyson Books, looked out at a similarly hostile landscape, populated by frequent challenges aimed at books exploring queer identities. Addressing those who were doing their utmost to censor these works, Alyson penned a 1992 op-ed in the New York Times. In it, he expressed his frustration with these challenges, writing, “What kind of moral system is threatened by competing ideas and real-life facts?” His question, still pertinent today, is complicated by another: what kind of moral system results from automation—a string of ones and zeroes?

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra