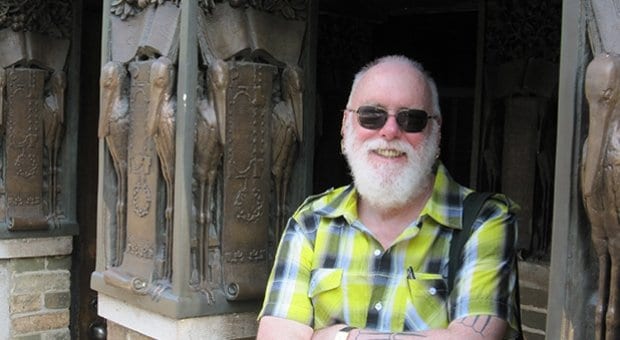

Charlie Hill was part of We Demand, the first gay protest on Parliament Hill. Credit: Brian Foss

Denis LeBlanc was just 18 years old in 1969, the year then-prime minister Pierre Trudeau finally succeeded, at least on paper, in removing the state from the bedrooms of the nation with the passing of Bill C-150. Leblanc was living in Moncton in a strict Catholic family at the time; it would be another three years before he reached the age of 21. Until then, as he puts it, he was jailbait. Meanwhile in Toronto, Charlie Hill was 24 and working toward a master’s degree in art history. Hill had come out of the closet in the mid-1960s and had been arrested for dancing with another man during a 1966 bar raid in Montreal. At the same time in Quebec, Carmen-Louise Lépine was going through high school. Also being raised religiously, she was not yet aware of her sexuality in those days and would go on to marry a man at the age of 19.

Bill C-150 had a profound effect on the lives of all three of these people, allowing each of them to live very differently than if homosexuality had remained illegal in Canada. But it has been an uphill battle, nonetheless. One of the biggest hurdles to overcome was the stigma. When Hill came out to his parents in 1965, their reaction was to take him to a psychiatrist. “He asked me, Did I want to change? I said no. So that was the end of that,” he says, chuckling. “My mother felt guilty; she went off to a psychiatrist, who told her it was parental: maternal control over a boy — the usual nonsense. So she had to unlearn as much garbage as I did.”

“I think what was really important about decriminalization was that it gave us freedom. We didn’t have to be afraid of getting arrested for being who we are,” Denis LeBlanc says. “I mean, it sounds so basic, doesn’t it?” Emboldened by the new law, LeBlanc dedicated much of his life to activist work — he was involved with Gays of Ottawa (GO), the city’s first organized gay movement, as well as EGALE and the Aids Committee of Ottawa. As part of GO LeBlanc’s focus was on breaking isolation and bringing people together. “We had these wonderful monthly dances that were bigger than any of the clubs, and that went on for 10, 15, 20 years, I think, in Ottawa. It funded the movement.”

He recalls going out with glue buckets and plastering construction boards with dance posters, hitting neighbourhoods where he knew other LGBT people lived in an effort to make Ottawa’s gays more visible to each other. “It was also getting the word gay out,” he says. “We were wanting the people of this city, at least, to know what the word gay meant.”

Across the bridge in Quebec, Lépine was gradually becoming aware of her sexuality; despite her Catholic upbringing and early marriage, she found herself being drawn to the few lesbians she did encounter. As a student, she took a part-time job within the government, where she struck up a friendship with a lesbian co-worker. “I liked her — she was funny, she was not outrageous, but she was outgoing and she was different,” Lépine says. She eventually accompanied her new friend to the Coral Reef, then Ottawa’s best-known lesbian watering hole. This began a journey of self-discovery that culminated in her leaving her husband in 1976 at the age of 23.

There was still a culture of fear surrounding homosexuality at the time, and public behaviour was still banned. “Back in the ’70s . . . it wasn’t acceptable,” Lépine recalls. The Coral Reef was situated across the street from the Ottawa police station and was subject to frequent raids, but even this wasn’t enough to keep people from congregating. Lépine says she remains very grateful to the owner for giving her and other LGBT people a place to come together.

Bar raids were also a part of Charlie Hill’s experience. “I certainly thought it was stupid,” he says, recalling his 1966 arrest. Hill and the young man he was dancing with were both acquitted but nevertheless had to go through the court system. He remembers the mother of another young man who had been arrested saying that her son planned to plead guilty because he lacked the funds for a lawyer. “That was interesting in terms of how justice is meted out. If you don’t have money, you don’t have a lawyer, at least in those days.”

The experience was ultimately a galvanizing one for Hill; tired of being pushed to the margins of society, he got involved with activist organizations, including the University of Toronto Homophile Association and GO, and was a part of the first gay protest on Parliament Hill, in 1971. “It was pouring rain is what I remember. We all got soaked,” he says. “I think it was important historically . . . I think just the example of it being done on the Hill for the first time was extremely important.”

These days, life is somewhat quieter for Hill, Lépine and LeBlanc. Hill is curator of Canadian art at the National Gallery of Canada, an organization he says has always been very supportive of him. Lépine works for the federal government and is involved with LOG (the Lesbian Outdoor Group), a group that brings lesbians together to socialize while enjoying outdoor activities in the Gatineau Hills. LeBlanc, who was diagnosed as HIV-positive in 1988, is kept largely housebound by emphysema. Despite his health challenges, he remains a committed activist, using the internet to mobilize aid for the international LGBT community in places like Uganda and Cameroon. All of them are optimistic about the future of the LGBT community in Canada; as LeBlanc stresses, the real need is for activists to focus outward in the hope that C-150’s legacy can be felt around the world.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra