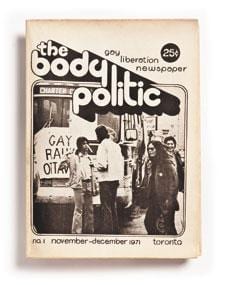

A photo of the We Demand protest was reproduced on the cover of the first issue of The Body Politic. Credit: Ryan Faubert

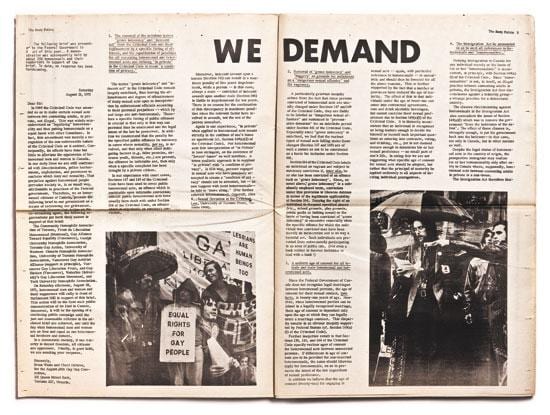

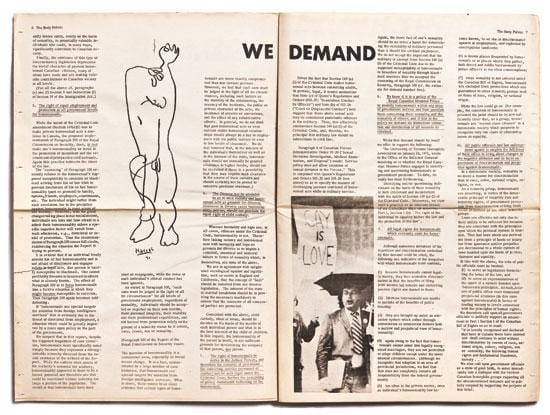

This is the We Demand brief, which was presented to Parliament in 1971. It is reproduced here from the first issue of The Body Politic. Credit: Ryan Faubert

At the bottom left of the first page, notice the names of two signatories: Brian Waite (interviewed on page 9) and Cheri DiNovo, now an Ontario MPP. Credit: Ryan Faubert

Forty years ago this summer, a group of about 200 gays and lesbians did something that had never been done before. They gathered on Parliament Hill to read a list of demands — the first time that Canadians had protested publicly for gay rights.

It rained. One car of protesters — en route from Toronto — was involved in an accident and missed the protests. At the time, few would have believed that the soggy event, which lasted less than an hour, would have such a lasting impact.

And yet, as we mark the 40th anniversary of the August 28, 1971, protest, it’s hard to underestimate the influence the movement had on three generations of gays, on the law and on Canadian society writ large.

Luckily, a photographer captured some of the protest. Bear in mind that cameras were less common in 1971 than they are now, and the technology meant that every picture that was snapped cost money — for film, for developing, and, often, for disposable flashes. That man was Jearld Moldenhauer, who went on to be a founder of the Body Politic.

In one photo, a young George Hislop stands under an umbrella, his round face beaming. In another, a woman with cropped hair brandishes a sign that says, “Lesbians are human beings too.”

In a third, a young man with a thick, dark beard and long hair stands on the steps of Parliament Hill, reading from a loose, crumpled page. He wears a wide belt, a polyether print button-down shirt and wire glasses, as was the fashion at the time.

At the time, Charlie Hill was a 25-year-old university student.

In an interview with Xtra from his Sandy Hill home, Hill, now 65, recalls the protest. Even though many hippies were involved, no one lit joints and there was no violence. Demonstrators marched in the pouring rain and danced around the Peace Tower. A second rally was held simultaneously in Vancouver, for those West Coasters who couldn’t make the trek to Ottawa.

Organizers chose Parliament Hill deliberately because they wanted to target federal, not provincial, lawmakers. It was also the second anniversary of the Criminal Code amendment that decriminalized same-sex relationships for people over the age of 21.

“All the demands were specific to federal law. That was the whole purpose of the demonstration. We wanted to publicize the demands we wanted for legal change. A lot of people, either gay or non-gay, thought there were no legal issues for gays. That was nonsense. There were still a lot of laws discriminating against gays. We did it in Ottawa because it was directed where federal laws were made,” says Hill.

Hill, looking every bit like a cast member of Jesus Christ Superstar, spoke on behalf of Toronto Gay Action.

George Hislop and Pat Murphy spoke on behalf of the Community Homophile Association of Toronto; Pierre Masson spoke for Montreal’s Front de Libération Homosexuel. American activist John Williams also addressed the crowd.

“I spoke for Toronto Gay Action, even though I wasn’t even a member yet. One of the people who wrote the speech, his car overturned on the way to Ottawa. David Newcomb and Herb Spiers wrote my speech,” Hill says.

Brian Waite, 67, also attended. A self-described “late bloomer” to gay liberation — he was 27 at the time of the protest — he, too, was there with Toronto Gay Action.

Waite clearly remembers the day of the protest: the cold rain, the bus from Toronto and the month it took to organize the event. But he says it was worth it because it helped him and his fellows let go of internalized self-loathing and let parliamentarians know they were no longer willing to be pushed around by the law.

“The word queer was very negative in its day. When we rolled into the bus, we said, ‘We’re here because we’re queer.’ We embraced that nasty word and we felt empowered,” says Waite.

“I came from a leftwing background. When I came flying out of the closet, everything became natural,” says Waite. “To be gay back then was to be radical. That’s why I hate conservative fags so much.”

After 40 minutes on Parliament Hill, people disbursed and went home.

The voices from the protest are beginning to slip away: Pat Murphy died in 2003, Hislop in 2005. Spiers passed away earlier this year.

“But I’m struck at how many legal issues and attitudes we were dealing with at that time. Especially with police harassment and oppression. Bureaucrats were using the law to discriminate against gays and lesbians,” Hill says.

Waite agrees but adds that it was legal interventions through the courts — not brave politicians — that eventually overturned the country’s most blatantly homophobic laws.

While many people were invited to attend We Demand, a large number declined because the fear of being publicly associated with or seen with a gay movement was too much to bear.

“A lot of people didn’t go, because they feared being caught on camera. But you don’t change something by accommodating yourself to oppression. People grew up with the fear of rejection: losing friends, family and your job. Those were all good reasons to adopt a mask, pretend to be something you’re not. We wanted to tell people that was no way to live,” says Hill.

What made We Demand so significant — other than its public nature — was that it was the first tangible result of a national network of organizations coalescing across the country.

“We Demand was a list of demands put together by a coalition of groups. These items basically formed the advocacy agenda for the next couple of decades,” says Tom Warner, author of Never Going Back: A History of Queer Activism in Canada.

For lesbians, getting involved with the burgeoning movement was tough, for two reasons. First, many were already heavily involved with the pressing needs of the feminist movement, which was pushing to legalize abortion and eliminate violence against women. And the attitudes of some gay men made it hard for dykes to feel a strong connection with the largely white, university-aged male activists who did much of the early organizing.

“Unfortunately, some of the men’s attitudes from the early gay groups weren’t helpful in giving any serious consideration to the items from the women’s movement, which had a lot of lesbians involved,” says Warner.

Still, women came out to We Demand, including Murphy, Marie Robertson and Sylvia Martin. Robertson and Martin, who both now live in Ottawa, decided not to contribute to this article, because their memories of the day are foggy.

Denis Leblanc, 60, was invited to the protest but was unable to attend because he was living and working in Moncton, New Brunswick.

“People now call it the We Demand protest. But we didn’t call it that at the time. We knew it as the first gay demonstration on Parliament Hill,” he says.

What Hill, Hislop, Murphy and the rest of the protesters could not have known was what would happen next.

Having clearly articulated a set of goals, gays and lesbians set out to achieve them. And they swiftly started to chalk up victories.

The issues, of course, turned out to be more complicated than simply removing bureaucratic barriers. Take immigration and refugee issues, for example: gay people won the right to immigrate openly six years after We Demand, but gay people still face barriers. Refugees are turned away for not appearing “gay enough,” and because refugee cases are adjudicated by a single person, bias and prejudice can still creep in. Meanwhile, immigration on the grounds of partner reunification retains dated definitions of what constitutes a relationship.

Even so, We Demand was the most visible early manifestation of a movement that succeeded beyond the wildest expectations of its early leaders.

The spinoff effects are hard to calculate precisely. Ed Jackson, 66, was not present at the We Demand protest, but he was circulating in Toronto’s gay scene at the time. “Practically everything itemized there has been specifically achieved. People were analyzing what they thought was possible. The thought of GSAs and equal marriage was beyond comprehension,” he says. In the months following We Demand, gay activists in Toronto began working on their next project.

After Guerrilla magazine, the reigning lefty publication in Toronto at the time, published a piece about gay liberation, some were unsatisfied.

“It was so heavily edited, and there was a concern we couldn’t get a proper representation even in a supportive newspaper,” says Jackson. “The Body Politic was clearly an outgrowth of We Demand. When people came back they said, ‘Now what?’ And then we said, ‘Let’s do a magazine.’”

For Waite, the lessons of We Demand percolated. He moved on to other projects, until a cold night in February, 1981.

“The next time I got heavily involved in gay liberation was during the bathhouse raids,” he says.

After Toronto police conducted a massive, coordinated arrest of bathhouse patrons, Waite and others were able to draw on some of the tactics used during We Demand, especially in the use of public protest, and in its swagger. In 1981, Toronto’s gays were again making demands, rather than politely asking for change.

And now, as We Demand–era gays and lesbians slide into retirement, Waite points out that they will again be pushed into activism. Retirement homes — notoriously conservative places, often run by religious groups — are simply not ready for queer people yet, he says.

“Should we allow some homophobic 80-year-old heap of shit to knock us around or push us back in the closet? What happens when nursing-home staff bathes a transgendered woman and finds a dick? No. We have to sensitize management,” Waite says.

A photo from the We Demand protest adorns The Body Politic’s first cover. Inside, the full text of the speech — a brief that was submitted to the House of Commons and was read aloud at the protest — sprawls over four pages.

The newspaper you’re reading now grew out of The Body Politic. Originally run by volunteer writers and editors, it is now a professional organization, using paid writers, with publications running in Ottawa, Toronto and Vancouver.

The Village committee is soliciting artists for a public art project about the We Demand protest. For more information, contact Glenn Crawford at glenn@jackofalltradesdesign.com.

Find the full text of the We Demand brief on the website of the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra