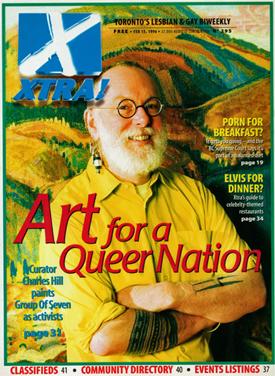

From the archives. Charlie Hill, from the cover of Xtra, February 1996. Credit: Paul Galipeau

Charlie Hill, 65, is known for two things: he is a pioneer in the Canadian gay liberation movement and he is a prominent curator at the National Gallery of Canada.

He set out on both paths at roughly the same time.

Hill was born in Ottawa in 1945. He grew up in Rockcliffe Park in an Anglican family and attended high school at Lisgar Collegiate Institute. His parents divorced when he was a child.

When he was 17, Hill told his parents he was gay.

It was the early 1960s. His father refused to accept his son’s sexuality. His mother blamed herself and sent him to a psychiatrist. The doctor offered no help, saying Hill was gay because he had a dominant mother and a submissive father.

“[The psychiatrist] laid this Freudian trip on me that being gay had something to do with my mother. I told him the only thing I was concerned about was being arrested in Montreal gay bar raids,” Hill says.

And indeed, in 1966, Hill and dozens of others were arrested in a gay club in Montreal. Because he was dancing with a male friend, he was charged with committing an indecent act in a public place.

“The police raided the club and arrested everyone. I got a discharge, but it is typical of the harassment conducted against gays in those days,” Hill says.

Becoming an activist did not happen overnight. When Hill was in his early 20s, the gay liberation movement was like the Wild West. Canadian gay organizations were in their infancy. In 1969, Hill joined the University of Toronto’s Homophile Association while doing his master’s degree in art history. Years before gay-straight alliances, he spoke about being gay in high school auditoriums. For the first time, students heard about homosexuality from a gay person.

“We looked to the black rights movement and women’s movement as our model and learned from them. We challenged the thinking that made laws against gays and tried to oppress us,” says Hill.

In 1971, Hill was part of the first large-scale gay rights protest in Canada: We Demand, on Parliament Hill. At the time, he was working in Ottawa as a summer student at the National Gallery library. In retrospect, he never thought the protest would be so widely discussed today.

“If you were gay back then, you were told, ‘You’re wrong or dirty.’ A lot of gay people felt this way at the time. It was easy to incorporate self-loathing. We wanted to tell people they needed to throw that garbage out.”

In 1972, Hill contemplated the direction of his life. He decided that if he was going to pursue gay activism, he would need some knowledge of sociology, psychology, journalism and politics. But being 27, he decided to pursue art history. And the National Gallery offered him a dream job, as assistant curator specializing in historic Canadian art. In 1972, he became Gays of Ottawa’s second president, a position he held until 1975. In 1980, the museum promoted him to full curator.

“The job was good. And to the credit of the institution, they hired me knowing I’d been active in gay liberation,” Hill says.

After the 1980s, Hill left gay politics and focused on his career. He was already known for his 1975 exhibition and catalogue Canadian Painting in the ’30s. In 2001, Governor General Adrienne Clarkson made him a member of the Order of Canada for his contribution to Canadian art and gay liberation. Hill lives with his partner of 16 years, Brian Foss.

How has sexual expression in art changed since you became a curator?

It’s much more overt. It’s more complex. That’s the sort of subject that comes and goes in art. Certain things become an interest in art, then people say, ‘It’s all been said.’ It goes away for a while. Then all of a sudden people say, ‘Nobody’s talking about this anymore. And it hasn’t all been said,’ and then we try to look at it in a new way. And then it comes up to the surface again.

When you say sexual expression is much more overt…

Years ago, you would’ve been jailed if you did certain things or published certain images. The type of sexual imagery we show today would’ve not been permitted back then. The work would have been seized. And if you’d shown it in your gallery you would’ve been charged. Dorothy Cameron in Toronto did a nude art show [in 1965] and police raided it. That was, again, gay liberation being part of a larger part of sexual revolution. Straight people also had to break down the walls of, and barriers of, Puritan oppression of any discussion of sexuality or sexuality in art. So gay liberation wasn’t just an isolated phenomenon. Everyone was working together. The walls were being attacked from different points of views from different groups of people.

In the US, the National Portrait Gallery censored David Wojnarowicz’s A Fire in My Belly. What is your take?

I think it was very stupid of them to censor this. The whole thing is very minor. It became a religious issue more than a gay issue, because of the statue of Christ. Christians came from a whole gamut of beliefs. The whole issue was about the artist’s comment on society, the oppression of the church and the values implied by varying ideas about Christ. It was a serious work of art, and it happened to be in the context of a gay show at a federal museum.

So you get this political pressure from the right threatening a federal museum in Washington, which would’ve possibly risked losing its funding. So that’s how they got at them. That’s what it was really about. The fact that the director succumbed to it — I think that was his big mistake. I don’t know why he gave in to the pressure and withdrew the video.

Did you know the director?

I didn’t know the artist or the director. I know one of the other artists [AA Bronson], who is part of General Idea. He wanted to withdraw his piece loaned by the National Gallery of Canada to the National Portrait Gallery of Washington. And that kicked up a big fuss. The issue there is two-fold. It became a confrontation about the right an artist has to control his or her artwork in where it is and isn’t shown. That is mixed up with the copyright issue — the control an artist has over his or her work. The National Gallery of Canada’s director said, We signed a contractual agreement with the National Portrait Gallery in Washington to loan this work. So our director wouldn’t pull it. Should he have pulled it? As a gay person who supports the artist, I would’ve hoped the gallery would’ve pulled it. But as a curator, I’m not going to comment.

Do you think we’ll see censorship like that within our own homegrown artwork?

I don’t see that type of censorship at this moment. The government has been fairly consistent in saying museums are independent and they cannot comment on what museums do. If, down the road, they cut the budget by 10 percent and next year you do something they don’t like… We’ll see what happens. But with other departments, every year they reduce the budgets to reduce taxes and the civil service. Of course, they’ve come in on a platform to reduce taxes and the civil service.

Even with cutbacks, will we still be able to see gay expression in the arts?

I think so. I don’t think the gallery would censor itself. I hope to God we don’t. In terms of last year’s Pop Life show, there was a whole room dealing with sexuality.

And the current gallery director is gay. I don’t see him censoring himself on those issues. And as I say, I don’t think we’ve seen direct pressure or censorship from the Conservative government. It’s a general indifference to the arts, which can be equally damaging because bit by bit your funding goes. It’s not just the gallery. It’s all the art institutions across the country who are dependent on some sort of federal government funding.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra