On September 14, 2000, the Toronto Police raided the queer bathhouse known as the Pussy Palace during one of their biggest events, which led to years of activism by the Toronto Women’s Bathhouse Committee and attendees.

The Pussy Palace was a queer, lesbian, bisexual and trans event that would unite queer women, including queer trans women, and others who were not cis men for a night of exploration, play and sex. It was organized by the Toronto Women’s Bathhouse Committee, a group that was committed to creating bathhouse parties for queer women, trans people and other non-cis men. The event took place in Club Toronto, a gay men’s bathhouse, that is now Oasis Aqualounge on Mutual Street. After two undercover female cops infiltrated the space, five plainclothes male police officers then entered and searched the club. No charges were laid, but in the weeks following, two volunteers were charged with Liquor Licence Act violations; these charges were later dismissed. This led to the committee launching a class-action lawsuit against the Toronto Police that they won in 2005.

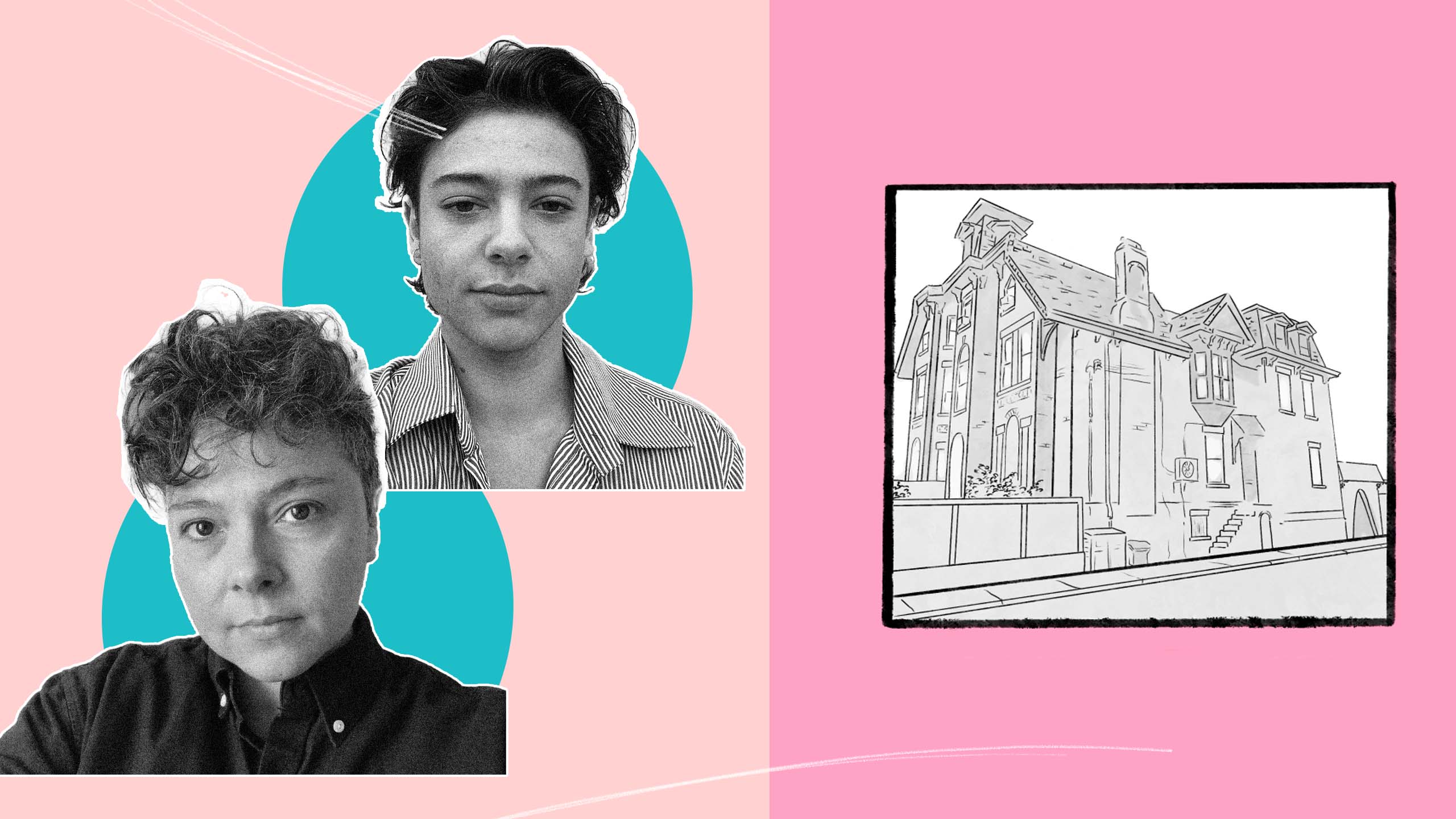

However, oral historians Alisha Stranges and Elio Colavito—who have been working on the Pussy Palace Oral History Project in collaboration with the University of Toronto Mississauga’s LGBTQ Oral History Digital Collaboratory and The ArQuives: Canada’s LGBTQ2+ Archives—have found that the raid is just one piece of the Pussy Palace story. Putting together the archive has become far more than just recording the details of the raid—it’s a way to document 10 years of queer lesbian and trans bathhouse gatherings.

The historians were deeply drawn to learning about the nuances of such a radical moment in sexual culture and queer history that largely only comes up in the context of the raid, if at all. There were very few spaces that existed how the Pussy Palace did, and provided the environment that people were looking for. Still today, it’s a rare find.

“There was so much joy and pleasure, freedom and, you know, politics, nuanced politics, in relation to the space that was more interesting,” Stranges says.

The project is funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, and spearheaded by Elspeth Brown, Elspeth Brown, professor of History at the University of Toronto, Mississauga, and director of the LGBTQ Oral History Digital Collaboratory. Up until now, the Pussy Palace raid was not well archived, certainly not to the level of the 1980s raids on Toronto’s male bathhouses. Brown wanted this project to fill that gap. Colavito says that oral history is “one of the only ways that we can often appropriately document the queer and trans past,” which made this project especially interesting to them. They started by putting out calls to find narrators, people who had been present that night and other nights, as well, to tell their stories.

“It was really slow at first. We started in February, I think, of 2021. It was like one [narrator] every two weeks,” Stranges says. “But then there just came a point where I think we hit one narrator who just knew so many people and was really interested in the project and just emailed all of her friends and was just like, ‘You have to do this.’ So we started to get tons of people.”

After that, the two were able to really dig in on creating a multitude of ways to explore the world of the Pussy Palace. Colavito worked on an Instagram series that illustratedAn Average Night, which went over how people learned of the event, how they got there, what the space was like and what interactions looked like inside. Together, Stranges and Colavito combed through more than 45 hours of interviews to produce video shorts that explore care in the Palace both in terms of aftercare after sexual exploration, and the mutual support that arose after the raid, sensory portraits of the space and the history of the event, not just the raid.

“As we’ve gone on in oral history, but certainly through queer and trans oral history, we’ve gotten to be a bit more creative about what we’re looking for, and how we’re archiving,” Colavito says. “Especially in terms of trying to archive in this particular circumstance, sense memories or how to talk about feeling.”

Stranges and Colavito have different focuses in their research: women and gender studies and history, respectively. Both have a collaborative specialization in sexual diversity studies. They started with an initial interview guide put together by Brown, and quickly found they would need to use different methods to get to the core of a narrator’s experiences. Stranges’s expertise brought a new approach to the concept of collecting oral histories by leading the narrators through a meditation on their time at the Palace.

“We would kind of get them to pause a little bit, breathe a little bit more deeply (and) imagine one or another location inside the Palace that came to mind,” Stranges says. “The first one would be the best one, and then to tell us, ‘What do you see? What do you hear? What do you smell? What’s the predominant colour that’s coming through?’ Some really rich content came out of that.”

These details became invaluable to Stranges and Colavito. Queer and trans histories are unique, especially in the context of an event that was designed by and for queer and trans lesbians and bisexuals. The oral historians wanted to use these guided techniques to delve deeper into the stories of the Palace, and not just focus on minute details that we are used to seeing in history books.

“Our larger goal wasn’t necessarily to figure out exactly what room the cops were in at what time or who was fucking who on the stairwell at, you know, 10:45 p.m.,” Colavito says. “We were more interested in that embodied feeling and what lingers over time in the mind. Oftentimes, they’re not the kinds of details that the typical historian would be searching for.”

Colavito says the team was able to find little moments, even in unrecorded conversations, where narrators would remember something that hadn’t come to mind in years, such as one narrator recalling the smell of Crisco permeating the space. This narrator noted that Crisco is a popular lube amongst gay men, who had control of the physical space the majority of the time when the Pussy Palace wasn’t running. While many narrators mentioned the smell of chlorine coming from the pool, this Crisco detail stood out to Colavito as a moment of interest when thinking about what it could mean for non-men to take up space in Club Toronto.

“We got really rich conversations about what it meant to present as butch, what it meant to present as femme, what those dynamics looked like in the ’90s and early 2000s, what they looked like in the kink space,” Colavito says. “The importance of a slip dress and combat boots, or leather and lace. We got more rich conversations about real relationships and dynamics between real people.”

An interview with narrator Nancy Irwin, an activist, writer, proud leather dyke and play party organizer who has been involved with the Toronto dyke kink and leather scene for over 20 years, stands out for Stranges.

“When it came to the raid itself, Colavito and Stranges were able to see trends among the narrators where this experience radicalized them in many ways, creating their own political awakenings as police abolitionists.”

“Early in the interviewing process, when we started changing the way we were asking about fashion. We asked her what she wore, and she said, ‘That’s not the important question. The important question is what’s in the toy bag,’” Stranges recounts. This comment from Irwin made the oral historians re-evaluate their interview questions again specifically to include it after realizing that toy bags would have been an important accessory at the Palace.

This led to the creation of a video short featuring Irwin discussing the importance of the toy bags, and what people brought along to the Pussy Palace. Kink was very present at these events and the toy bags, the researchers discovered, played a key role in how people navigated the space.

When it came to the raid itself, Colavito and Stranges were able to see trends among the narrators where this experience radicalized them in many ways, creating their own political awakenings as police abolitionists. After the raid, many of the narrators, who were already a part of the Toronto Women’s Bathhouse Committee and some who joined post raid, participated in the 52 division protests.

“[There was a theme of] anti-queer policing outside of the context of the Palace, and putting it in a broader historical narrative about the unfortunate relationship between police and queer people,” Colavito says. “Looking at it through the lens of the 2020s, a lot of narrators were able to even look beyond and locate that in conversation about the problems of policing more broadly.”

This anti-police sentiment has continued: in 2016, the Toronto Women’s Bathhouse Committee rejected the apology issued by the Toronto Police for the Pussy Palace raid. In 2020, the committee officially disbanded and donated the remaining funds they had to the Trans Pride Toronto organization in order to help the most marginalized members of the community.

In many ways, this experience has come full circle for narrators as Myron Demkiw, one of the officers who participated in the raid, was appointed chief of police for the Toronto police on September 15 of this year.

“The cops were really very destructive. And they spent plenty of time harassing women—like ones who stayed behind closed doors. And they were looking at us in a way that men on the street often do—leering, lecherous men. And now one of them is the chief? Go figure,” Irwin commented by email. “Our community has Pride because of police harassment. We don’t need them taking over our Pride parade. Let’s not forget they are the sole reason we have it! We were fighting back against police brutality.”

The pain of this appointment hit hard; the announcement came as Stranges and Colavito released the latest video short that specifically looks at the raid itself. The historians sent the video to narrators and received praise for the work, as well as deep anger and frustration to hear of the appointment.

“The most shocking bit was the quote from board chair Jim Hart, who called Demkiw a ‘dedicated public servant’ who is ‘committed to building and enhancing trust with the diverse communities we serve,’” Stranges noted. “Left me wondering what evidence Hart has to back up this statement, and what evidence he must ignore in order to make it.”

Stranges and Colavito worked several angles to try and collect the oral histories from officers who raided the Palace, wanting to see if this part of the history could also be captured. However, they had no luck in this venture.

“In extending an opportunity to build and enhance trust, the research team was met with radio silence. As oral historians hoping to document as many perspectives as possible, it was disappointing not to collect narratives from the officers involved,” Colavito and Stranges said in a written statement on the appointment. “As queer and trans Torontonians and staunch abolitionists, it’s unsurprising that our invitation to ‘build a bridge’ was refused.”

The work that Colavito and Stranges have done isn’t quite over yet, either. They have one final offering planned that would allow people to interact with the Pussy Palace and the raid through an immersive digital exhibit that they hope will be finalized by the end of the year. With this exhibit, people will be able to click through a representation of the space and hear a narrator talk about their experiences in the physical location.

“Part of the design of the digital exhibit is that you’ll be able to go and visit the Palace. There’s nothing about the raid there. If you want to learn about anti-queer police hostility in relation to the raid, you have to go to an entirely different section, or you can choose just to not go and visit it,” Stranges said noting that since queer histories are often focused on violence, they wanted to give people the option to see what the Palace was without the raid.

“The raid serves as an entry point to thinking about this history in the queer women’s community. But beyond the threshold of the Palace, there’s a lot more than just the police busting a good party. There’s a lot more to it than that,” Colavito says. “If we could do the project differently over again, it wouldn’t be a project about the raid, it would be a project about the space in which a raid is one of the focus points.”

The years of the Palace can be remembered, interacted with and heard through the digital exhibition and the other interactive creations Stranges and Colavito have worked on.

Correction: October 7, 2022 11:18 amThis story has been corrected to address errors, including misspellings of names and an inaccurate job title, and to provide more clarity about several aspects of the project.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra