Four decades ago, a cataclysmic shift took hold of Toronto’s splintered LGBTQ2S+ community. In a deliberate attempt to eradicate one of the city’s sole bastions of queerness, two hundred cops stormed several of the city’s gay bathhouses, bashing in walls and mass arresting the people inside. The raids were part of what police called Operation Soap.

Many of the police were in plain clothes, but the thundering of boots indicated to many unsuspecting men inside the bathhouses that something was awry. Some men clung to each other in fear as police hurled homophobic insults and violent threats their way. Many men were half-naked, barred by police from retrieving their clothes and forced to endure the cold February air before being thrown into the backs of police trucks. When the bathouses were raided, some men were having sex while others were simply resting. Police battered down doors and placed men in handcuffs indiscriminately, humiliating and degrading everyone in their wake—many of whom were still firmly in the closet and trying to survive in the oppressively homophobic social climate of 1981.

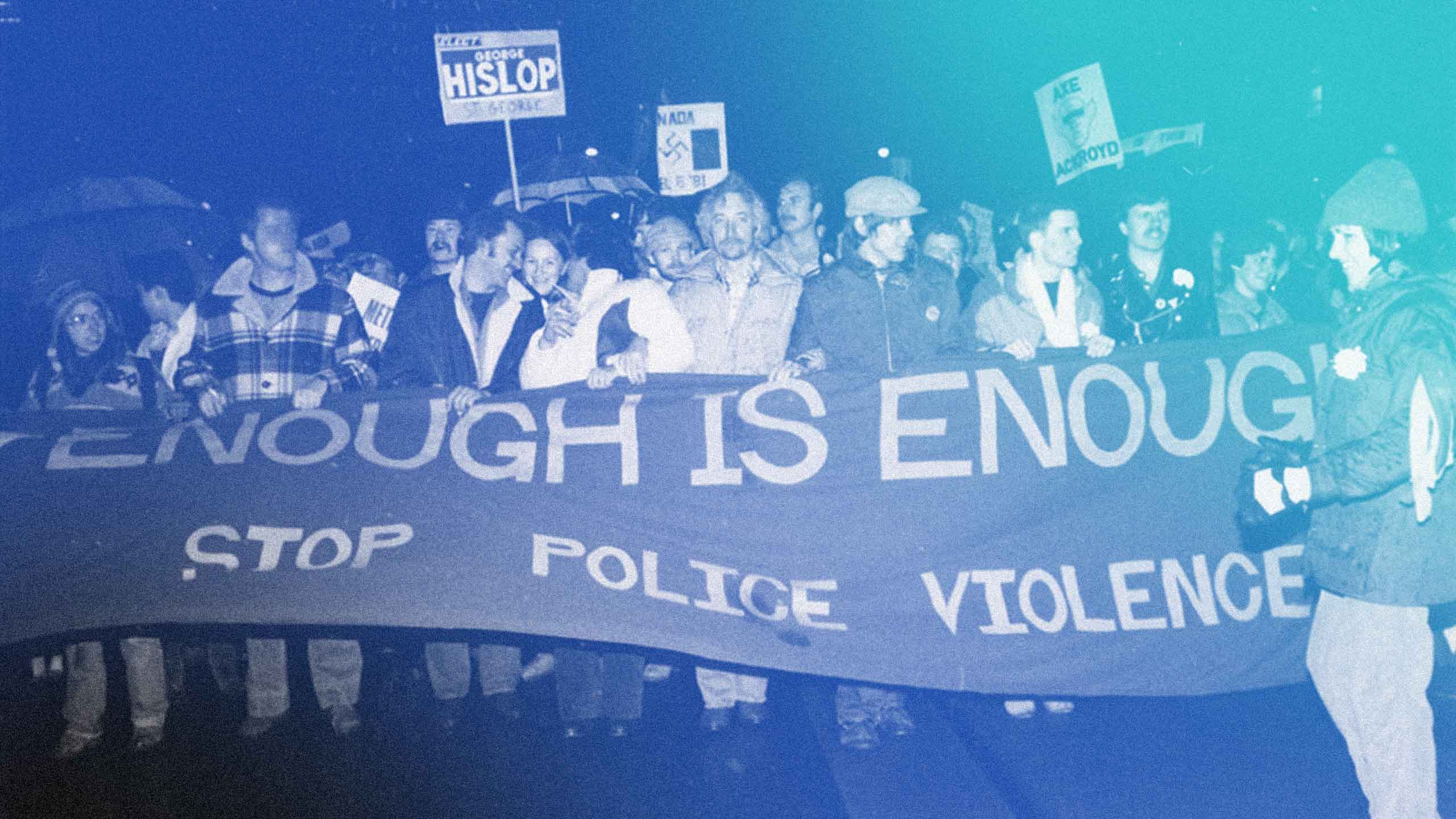

What followed was the emergence of the modern gay rights movement in Canada. Queer folks took to the streets in the days that followed the raids, overwhelming police and declaring with unrelenting force that enough was enough.

But the Toronto bathhouse raids were hardly the first of their kind, and they were far from the last. Queer folks have always resisted oppression, while those in positions of power—including police and government—have often positioned themselves as our most adamant and forceful oppressors. Broken and beaten down, Toronto’s LGBTQ2S+ community rose out of the raids determined to fight for emancipation.

As the 40th anniversary of the raids approaches, here’s everything you need to know about the context and aftermath of what has been called “Canada’s Stonewall.”

What was the state of queer rights in Canada before the 1981 raids?

In 1969, the Canadian government “decriminalized” homosexuality. The state, to paraphrase Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, was found to have no place in the bedrooms of the nation. Over the years, the Government of Canada has been quite self-congratulatory over this move, commissioning a special coin in 2019 to celebrate 50 years of gay rights (the coin depicted two overlapping faces with the word “equality” scrawled in English and French).

But for Tom Hooper, the idea that queer people achieved equality in 1969 is preposterous. Hooper is a historian whose research has often centred around Canadian bathhouse raids—including the raids of 1981. He has meticulously documented the persistent efforts on the part of both police forces and governments to silence, arrest, beat and humiliate queer people. He says the decriminalization of homosexuality is directly linked to the many co-ordinated raids across the country that followed 1969.

“In 1969, no laws were repealed,” Hooper explains. “Because of how narrow that change actually was in 1969, it almost pointed police to the baths. It told them to look for places where we were outside the ‘bedrooms of the nation.’”

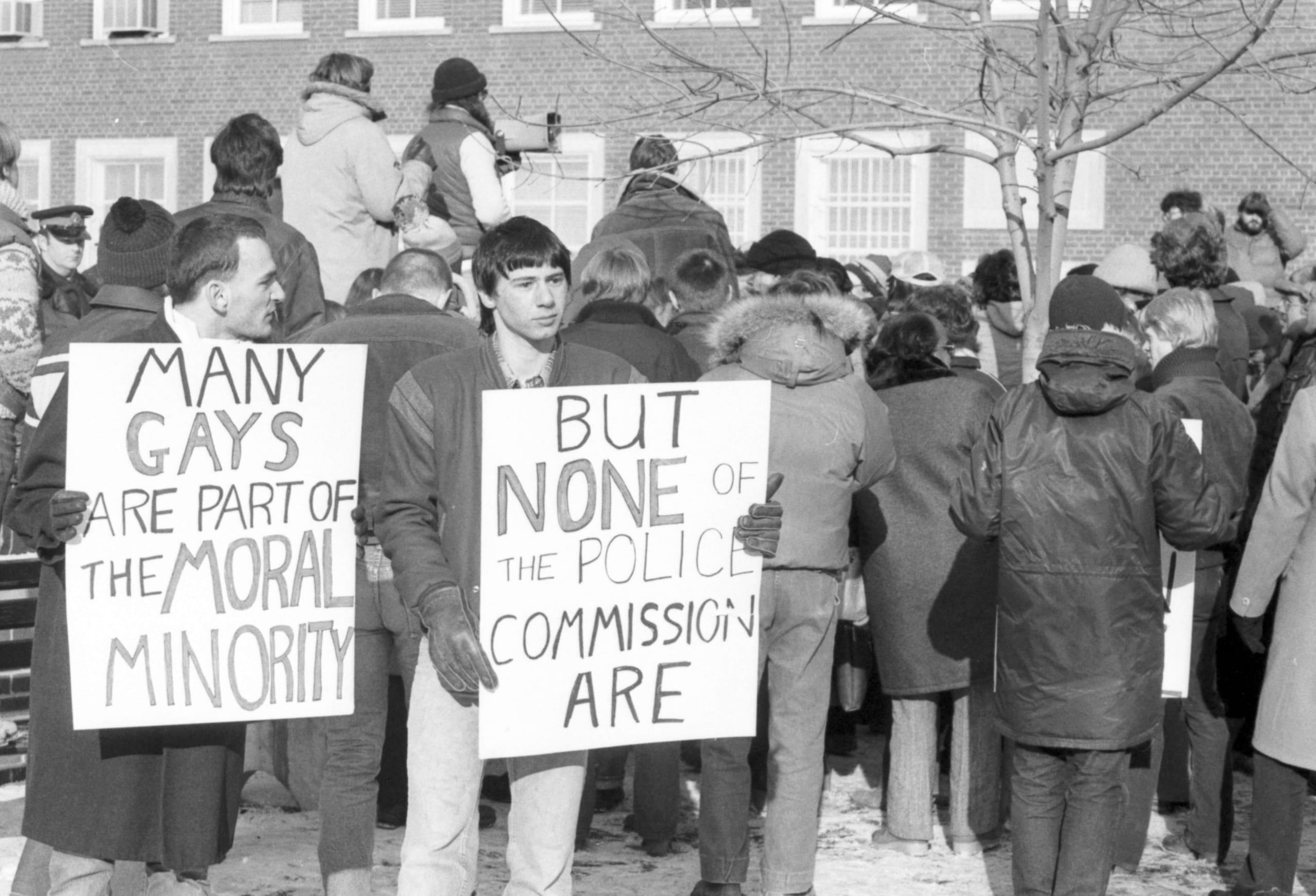

An overflow crowd waits outside Metropolitan Toronto Police Headquarters on Jarvis Street while their supporters argue for a public inquiry, Feb. 12, 1981. Credit: Barrie Davis/The Globe and Mail

Hooper has tracked bathhouse raids as far back as 1968, when 35 people were arrested at The International in Toronto. Since then, according to Hooper’s research, more than 1,400 arrests have occurred at bathhouse raids between ’68 and 2004, when two people were arrested at the Warehouse Spa and Bath in Hamilton, Ontario for “indecent acts.” These raids have occurred in multiple Canadian cities, although Operation Soap yielded the most arrests in one night.

The 1970s—the decade that followed the so-called decriminalization—was a tumultuous period for queer folks in Canada. Although their private sexual interactions were technically legal for the first time, LGBTQ2S+ people frequently faced police harassment and could be charged with any number of offences, including buggery (often referring to anal sex) and gross indecency (often focused on oral sex). Homophobia ran rampant, and neither the Ontario Human Rights Code nor the Canadian Human Rights Act included sexual orientation or gender identity as protected grounds—meaning that it was legal to discriminate against queer and trans folks merely for being queer or trans. Coming out was a dangerous thing, and bathhouses represented a place where queer folks—typically cisgender queer men—could have sex without fear of being reprimanded or outed.

“Although their private sexual interactions were technically legal for the first time, LGBTQ2S+ people frequently faced police harassment.”

But the LGBTQ2S+ community was resilient. Some began to organize in an effort to effect legal change against systems that sought to oppress them. Glad Day Bookshop—Canada’s first LGBTQ2S+ bookstore, now the oldest surviving queer bookstore in North America—opened in 1970. A year later, the Body Politic, a radical gay newspaper and a predecessor of Xtra, was founded. Activists also sought to reform the Criminal Code and the Ontario Human Rights Code, but the lack of safeguards for queer people to gather and be themselves made it difficult to co-ordinate and fight.

Meanwhile, institutional powers remained relentless in their efforts to snip activism off at its roots. Bathhouse raids were common. Censorship of LGBTQ2S+ content also abounded: The Body Politic was raided in 1978, and Glad Day was raided in 1982. After 28 were arrested at Toronto bathhouse The Barracks (also in 1978), a few gay activists, including former politician-turned-bathhouse owner Peter Maloney and bathhouse owner George Hislop, decided to take action.

A man demonstrates after the raids in 1981. Credit: Courtesy Nancy Nicol/The Arquives

They co-ordinated a fund for the legal costs of those arrested at The Barracks and held a press conference condemning all the raids, including those at The Barracks and the Body Politic, and demanding an end to anti-gay police activity. That small group of activists eventually evolved into the Right to Privacy Committee (RTPC), a landmark organization that led much of the charge in the late ’70s and early ’80s to secure equal rights for gay and lesbian folks.

Some in power began to publicly support the gay community: In the late ’70s, Toronto mayor John Sewell went so far as to publicly endorse Hislop for a city council bid. In response, fundamentalist Christian and right-wing groups launched a media campaign against both Sewell and Hislop, painting them as immoral and sinful. In the city’s 1980 election, both Hislop and Sewell lost, leading some to blame their association with the gay community for their failures.

What happened the night of the bathhouse raids of 1981?

Tim McCaskell was not in the Gay Village when police stormed the baths. McCaskell, a storied gay activist who was an integral part of the Canadian gay rights movement in the 1970s and ’80s, was a reporter for the Body Politic at the time. On the night of Feb. 5, 1981, McCaskell’s editor called him, abruptly woke him up and told him to get to the Village, pronto. “They’re raiding all the baths,” he said.

McCaskell darted to the Village and began interviewing the men who avoided arrest. He saw bathhouse customers being loaded up into police vans by cops. Police were everywhere—arresting men, loitering and occupying the space where queer folks were supposed to be safe. “They looked like a pride of lions that had just killed an antelope,” McCaskell tells Xtra. “They were standing around, very pleased with themselves, and didn’t pay any attention to the people outside because they already had their prey inside.”

What McCaskell did not know at the time is that he bore witness to history: The execution of Toronto Police’s Operation Soap.

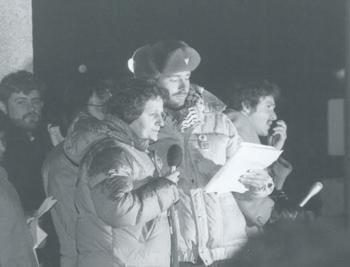

Tim McCaskell, pictured with Pat Murphy, at the Feb. 20, 1981, bathhouse riot. Credit: Courtesy Harold Gillis

Staff Inspector Donald Banks, who was in charge of the Morality and Intelligence Unit of the Toronto Police Service, rounded up 200 officers to invade the baths and arrest anyone doing anything that could be considered an offence, including masturbation, oral sex, anal sex, prostitution or group sex. The officers gathered at 7 p.m., and by midnight they had raided four Toronto bathhouses—The Barracks, Club Baths, Richmond Street Health Emporium and Romans. In total, 306 were arrested.

At the time, it was the largest mass arrest in Canada since the War Measures Act was invoked during the October Crisis of 1970. Additionally, the police caused enormous damage against the bathhouses themselves; it’s estimated that $35,000 of property damage was dealt to the buildings by police.

What happened after the raids?

Operation Soap caused the gay community’s fury against the police and the city to reach a boiling point. Activists like McCaskell began to call for a protest against the police’s actions on the following day, Feb. 6. The Body Politic passed out a pamphlet associating Operation Soap with the defeat of Mayor Sewell by Art Eggleton. By midnight, a crowd of several thousand gathered to listen to speeches and march to Queen’s Park. They overwhelmed the organizers, who had anticipated a crowd of just a few dozen. Police showed up once the crowd swelled, but they could do little to control it. The protesters peacefully walked to the provincial legislature, launching now-iconic chants like “Fuck you 52!” (a reference to the 52nd division of the Toronto Police, which organized Operation Soap) and “No more shit!”

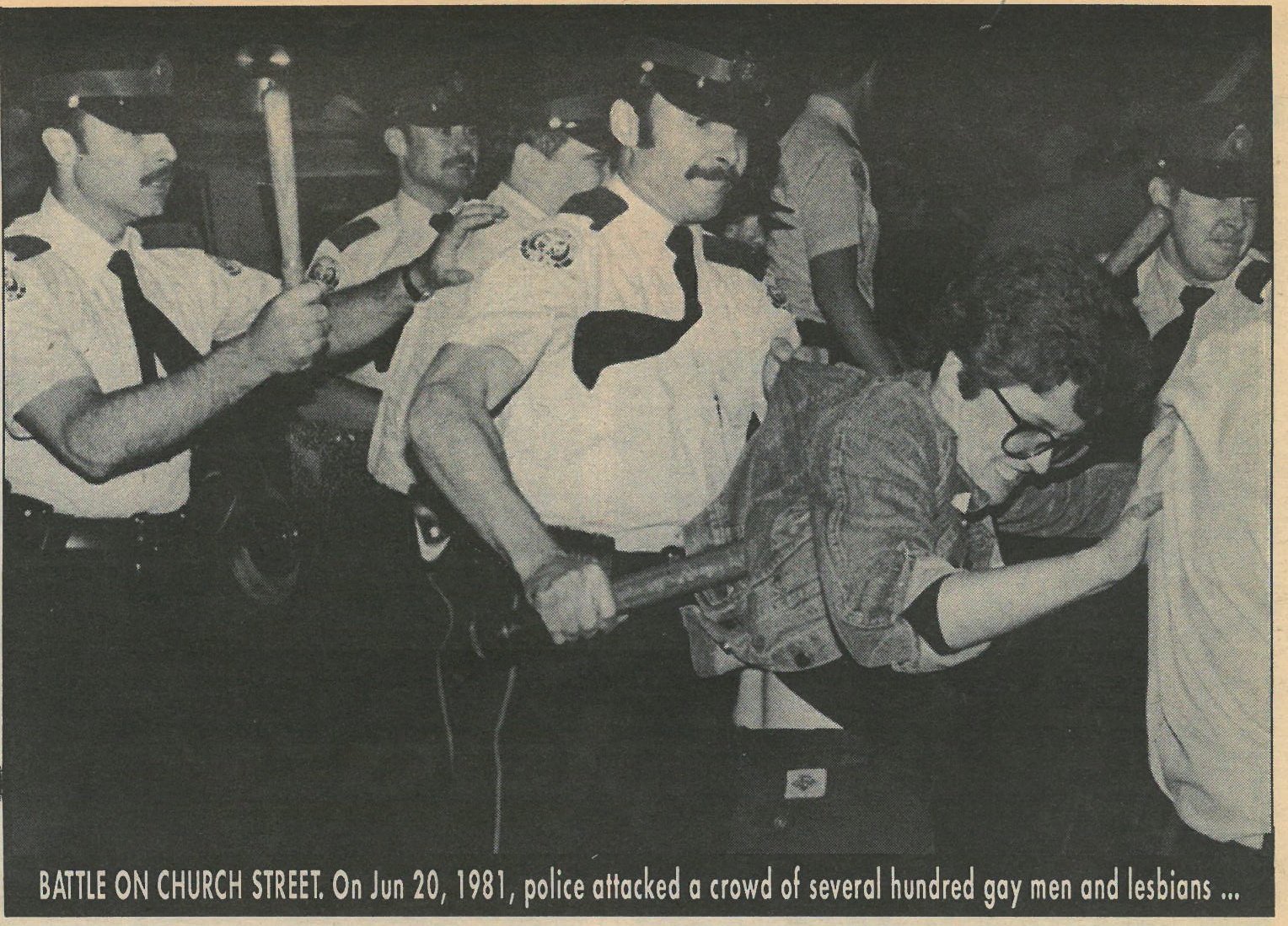

People protest in the streets of Toronto after the bathhouse raids on June 20, 1981. Credit: Courtesy Gerald Hannon

For McCaskell, the demonstration marked a turning point for the gay community in Toronto. They were finally unified against a common enemy: The police. “The demonstration—that’s where I think the lights went on for so many people,” he says. “They suddenly realized, ‘Shit, we’re powerful! We can do something about this!’”

What effects did the protests have on LGBTQ2S+ rights?

The RTPC saw the demonstration as an opportunity to enact some real change. The committee made a focused effort to use the system against itself. They harnessed the momentum generated on Feb. 6 and zeroed in on specific goals—namely, the elimination of sodomy offences like buggery and gross indecency from the Criminal Code of Canada. They funded the defences of many of those arrested during Operation Soap and helped get a number of them acquitted.

Brent Hawkes, a Toronto gay activist and clergyman, began a hunger strike shortly after the raids. Hawkes demanded that the police begin an inquiry into its homophobic practices. City council members Pat Sheppard and David White asked for the same. In July 1981, Mayor Eggleton, after significant prodding from community members and city council, asked civil rights leader Daniel Hill to lead an inquiry into the city’s relationship with the queer community, who passed it off to Arnold Bruner, a law student and journalist. Bruner’s report eventually concluded that there was, in fact, a gay community, that the bathhouses were integral social and sexual spaces and that there should be a “police/gay dialogue committee” to act as a liaison between the two groups.

“Bruner’s report concluded that there was, in fact, a gay community, and that the bathhouses were integral social and sexual spaces.”

Perhaps the most enduring, tangible and immediate consequence of the demonstrations is the official birth of Pride Toronto. Following the protests, Lesbian and Gay Pride Day was legally incorporated, and the first official Pride took place on June 28, 1981, in Grange Park. It was advertised as a reprieve from the political tension the queer community had gone through that year, and as “an afternoon of fun and frolic.”

The efforts of gay activists succeeded in many ways by the end of the 1980s. In 1987, buggery and gross indecency were combined into “anal intercourse” in the Criminal Code, which was legal for those above age 18. In 1986, sexual orientation was added as a protected ground in the Ontario Human Rights Code. (Gender identity and gender expression were added in 2012.)

What still needs to be addressed in the decades after the raids?

The efforts of activists like the RTPC are not without critics. Their activism was intentionally limited in its scope, often excluding other members of the community, like lesbians and trans folks. Queer women in particular continued to be targeted long after Operation Soap; in 2000, the women’s bathhouse Pussy Palace was raided and shut down by police.

In 2016, the Toronto Police issued an apology to the LGBTQ2S+ community for the bathhouse raids. Then-police Chief Mark Saunders expressed regret on behalf of the Toronto Police Services for the actions taken during that night in 1981. But many community members felt the apology was empty, given the ongoing strife between police and LGBTQ2S+ people.

Tim McCaskell, who was at the forefront of much of the activism surrounding the raids, agrees that many of the problems that spurred Operation Soap still exist. He points to the occupation of Toronto Pride in 2016 by Black Lives Matter, who demanded uniformed police be excluded from the parade, as an example of the progress that still needs to be made.

Black Lives Matter Toronto at Toronto Pride on June 25, 2017. Credit: Nick Lachance/Xtra

“For Black Lives Matter, having police in the parade is an affront. For white gay men, this is a sign of progress, because these guys that used to beat us up now want to be in our parade,” McCaskell says. “If queer people start to become a target again, will we be able to produce the same kind of community unity that it took to stop that movement in its tracks back in 1981? I don’t know the answer to that question.”

He also says a full retrospective understanding of the bath raids can provide a template for how queer people approach their relationship to police. Importantly, the community unity that brought about change in the 1980s was only made possible through an intersectional approach to what unity meant. At the time, police were brutalizing white gay men in comparable ways to how they are known to disproportionately target Black folks, Indigenous folks and other people of colour.

“What we did, specifically focused on the question of the police, was to say, ‘We need to try to produce some sort of unity between these communities, knowing that we don’t all agree with everything. But listen, we all need to be on the same page in terms of community accountability of the police,’” he says.

Now that the police no longer specifically target white gay men, that sense of unity has dissipated, says McCaskell. But in the past year, the world has been reckoning with the ways our police forces are instruments of oppression for racialized people—just like they terrorized and oppressed white queer folks 40 years ago. Some within the queer community have forgotten that the rights we celebrate today only came about through a partnership with non-white queer folks. For McCaskell, reconciling that forgotten sense of community through a recollection of our shared history is the only path forward.

“I think that it’s important to talk about the bath raids because you need to talk about the conditions that allowed us to produce the kind of unity we needed to fight back,” he says. “We’ve lost them now, but reproducing them needs to be a really important component of queer politics.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra