Credit: John Webster

A letter from a top government official confirms that Ontario has halted discussions with a coalition fighting to reduce the use of criminal law in HIV-nondisclosure cases.

The letter, from Mark Leach, acting deputy attorney general, to the Ontario Working Group on Criminal Law and HIV Exposure (CLHE), says that the province will wait until the Supreme Court of Canada releases its decision in R v Mabior before resuming work with the group.

Leach is the highest ranked civil servant in the Ministry of the Attorney General. He declined to be interviewed for this article.

The Mabior case was argued before the Supreme Court in February. The decision is likely to be released later this year. But the case has been in front of the Supreme Court since at least December 2010 — well before the province began working with HIV activists on this file.

At the centre of Mabior — and of the work of the CHLE — is the legal obligation of HIV-positive people to disclose their HIV status before having sex. The Supreme Court is considering the impact of condom use and low viral loads, which greatly decrease the risk of transmission, on criminal prosecutions.

This is the latest in a string of erratic moves from the ministry. In 2011, the Province of Ontario won the right to intervene in Mabior before the Supreme Court, only to withdraw from the case before it was heard. Then, it submitted a brief to the Ontario Court of Appeal asking that court to greatly expand the use of the criminal law in nondisclosure cases, even though the Ontario court will be bound by the decision of the Supreme Court of Canada when it’s released.

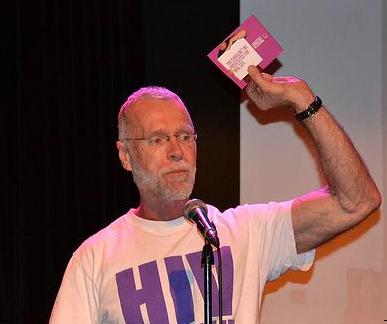

Eric Mykhalovskiy works with CLHE and is a sociology professor at York University who studies HIV-nondisclosure cases. “Ontario, there’s no question, leads other provinces by far in HIV-nondisclosure prosecutions,” he says. “The Ministry of the Attorney General has taken a particularly aggressive stance.”

Before its latest about-face, Ontario had agreed to develop prosecutorial guidelines, which would limit how and when crown attorneys could prosecute such cases. In the UK, for instance, guidelines limit prosecutions to cases of actual transmission where there was intent to transmit HIV or recklessness about transmission.

Leach’s letter says that CHLE was informed that the process would be halted in December 2011, two months before Mabior was heard at the Supreme Court. However, letters to the province dated June 1, 2012, and June 22, 2012, show the CHLE was still trying to work with the attorney general’s office as late as this summer.

Tim McCaskell, a long-time HIV activist who is also involved with CHLE, says the decision to stop working with the group will delay progress on many issues that don’t have anything to do with the case before the Supreme Court. That list includes guidelines on how to qualify expert witnesses, training crown attorneys about the realities of HIV transmission, and how police handle pretrial publicity.

“And if not — if they’re really serious about waiting for Mabior — there should be a moratorium on prosecutions until we get a decision,” McCaskell says.

Mykhalovskiy calls on the attorney general’s office to find common ground on some of the less contentious aspects of the CLHE’s work.

“When you have an impasse, it would be helpful to come to an agreement on smaller issues, and then try to build on that experience.”

Data collected by Mykhalovskiy shows that prosecutions in Ontario have been consistently high since 2004. He says that liaising with the government is just one part of the HIV community’s multiprong strategy. Another prong is to make sure defence lawyers are equipped to defend HIV-positive clients.

“We need a broader definition of what criminal law reform is,” he says.

A further strategy, Mykhalovskiy says, is to “stop the supply of complainants.”

“I’m worried that there is a changing standard where younger gay men find out they’ve been exposed to HIV and they think that they should go and press charges,” he says. “That’s the last thing that gay men should want to do, especially if there’s been no transmission.”

If the HIV community can find out what’s at the root of complaints, and then find alternatives that meet the same needs, some cases can be diverted from the criminal courts, he says.

“There are a number of cases of people complaining to the police and then regretting it. And once you complain, you can’t undo it. Police can press ahead with charges.”

A short written statement from Marya Winter, a spokesperson for the ministry, confirmed that prosecutorial guidelines will not be developed until after the Supreme Court’s decision is released. Winter declined to comment further.

“It would be premature to address prosecutorial guidelines ahead of this ruling,” she wrote. “As these matters remain before the court we will not be commenting further.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra