Credit: John Webster

The Supreme Court of Canada is preparing to hear a case that could reshape the contours of our sexual responsibility in the eyes of the law.

The hearing, slated for Feb 8, will consider Manitoba and Quebec cases where people did not disclose their HIV-positive statuses to sexual partners. It will be the first time in a decade that the court has tinkered with the rules, first set out in 1998’s Cuerrier decision, which require partners to disclose anything that would constitute a “significant risk of serious bodily harm.”

It’s hard to overestimate the effects of the 1998 decision. Since then, Canada has seen more than 130 people charged for not telling sexual partners they are HIV-positive. Similar charges are now being laid against people with other sexually transmitted infections, including hepatitis and herpes.

HIV advocates say that public health — rather than the criminal law — is the best place to deal with nondisclosure. And even in cases where the law should intervene, it is out of all proportion for a poz person to face charges of aggravated sexual assault, says Cécile Kazatchkine of the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network. It’s a popular charge among prosecutors, and it carries a maximum sentence of life in prison.

On the one hand, the law of disclosure is becoming more harsh. At the same time, treatment options have vastly improved, making infection more of a chronic and manageable disease and less of a death sentence.

And that’s causing some people to change their minds. Isabel Grant, a law professor at the University of British Columbia, says her first reaction in the 1990s was, “of course that should be criminal.” But she thought past that reaction, and she urges others to do the same.

“Are we doing anyone any good by prosecuting these cases?” she asks. “I would like people to ask themselves, Why are we singling out HIV?”

At a practical level, mandating disclosure poses problems. For many, talking about HIV is no simple thing. For some people, it’s next to impossible, emotionally and psychologically. And the stakes are high. People who talk about being poz run the risk of losing control of how that information is circulated.

“Some people lose jobs, some people lose loved ones, some people lose the support of their families for disclosing,” says Grant. “People risk violence if they disclose.”

Tim McCaskell, a spokesperson for AIDS Action Now, agrees.

“If I disclose to someone in a small or tight-knit community, they’re not a lawyer or a doctor. They’re under no obligation not to tell anyone,” he says. “Often, the more vulnerable a person is, the more complicated that thought process becomes.”

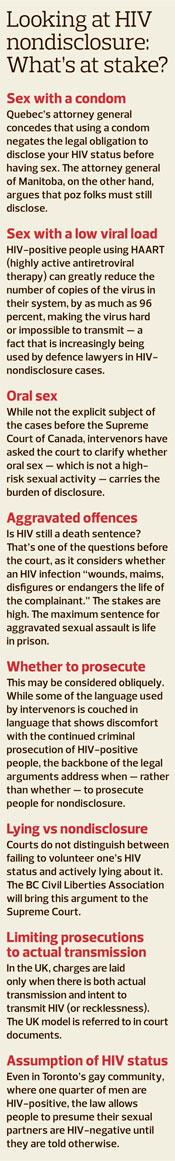

That’s why if a poz partner uses a condom, Grant says, there should not be a duty to disclose. That way, poz folks can protect their partners, even if they can’t or don’t disclose their HIV status. The Supreme Court has never definitively ruled on whether condom use protects poz people from prosecution.

Other factors are perhaps trickier. A person on a drug regimen plan like HAART (highly active antiretroviral therapy) can greatly reduce the number of copies of the virus in their system, by as much as 96 percent, making the virus hard or impossible to transmit — a fact that is increasingly being used by the defence in HIV-nondisclosure cases.

In the past, Grant publicly expressed concern about the workability of viral load defences in criminal prosecutions. She has since changed her mind on this, too.

“I still think viral load is problematic,” she says. “But I think that if you’re going to maintain the significant risk test, it doesn’t mean anything if you don’t take into consideration low viral load.”

The two cases before the Supreme Court each touch on viral load and condom use. The court will hear appeals in both cases together in a tightly compressed format in a single day. The Manitoba case, Mabior, deals with multiple complainants, during a period in which the accused had a low viral load and sometimes used condoms. In the Quebec case, known as DC (the accused’s initials), a woman is charged with failing to disclose her HIV status to her partner before the first time they had sex. She disclosed afterward, and the relationship continued for several years. No partner in either case became HIV-positive as a result.

But when it comes to the complexities of sex and relationships, condoms and viral load are just the tip of the iceberg. Do people have the same burden in all sexual situations? Is there a difference between lying and failing to volunteer information?

The BC Civil Liberties Association, an intervenor in the case, argues that when it comes to nondisclosure — rather than lying — not all sexual situations are the same.

“You don’t have a right to have unprotected sex,” says the BCCLA’s Micheal Vonn. “Cuerrier created an entitlement to be uninformed. That’s predicated on a whole raft of assumptions. Like, that everyone knows their status, which, of course, they don’t.”

But, she adds, “The onus shifts subtly in circumstances where people are presumed to be monogamous” and aren’t using condoms.

At the moment, there’s no hard and fast rule for when an HIV-positive person is under a duty to disclose. Poz folks have been prosecuted for sex with condoms and sex with low viral loads. In other cases, those factors have been a defence.

Everyone agrees that the law needs to be clarified. The danger is that the court may do so by removing the defences rather than affirming them, says Kazatchkine. That would impose a duty to disclose in all circumstances, even when giving a blowjob, a scenario which poses virtually no risk to a HIV-negative partner.

The best possible outcome would be for the court to follow the science wherever it goes, rather than relying on gut reactions to HIV, says McCaskell.

“The best possible outcome? Not to overturn Cuerrier, but instead to establish factors in a scientific assessment,” he says. “I think they would want to leave it up to an expert witness.”

Everyone has a stake in this decision. Poz people stand to lose the most from an adverse decision, but every sexually active Canadian will be affected. Not just because the case has the potential to change our legal obligations to each other, but because it could hamstring sexual health workers and scare some away from getting tested for HIV in the first place.

“A bad decision of the Supreme Court,” says McCaskell, “will be very bad for the health of Canada.”

In Toronto:

Day of Action Against the Criminalization of HIV

Calls to action, a march to Old City Hall & street theatre

Hosted by AIDS Action Now

Mon, Feb 6, 5:30pm

Church of the Holy Trinity, 483 Bay St

In Ottawa:

Criminal Sex? Women, HIV & the Injustice of the Law

Film screening & discussion

With guests Alison Duke, Dr Mark Tyndall

Hosted by the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network and Canadian AIDS Society

Mon, Feb 6, 6:30pm

Location TBA

Below is a video interview between Xtra’s Matt Mills and Richard MacKay who has been researching Gaetan Dugas, the so-called “Patient Zero”.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra