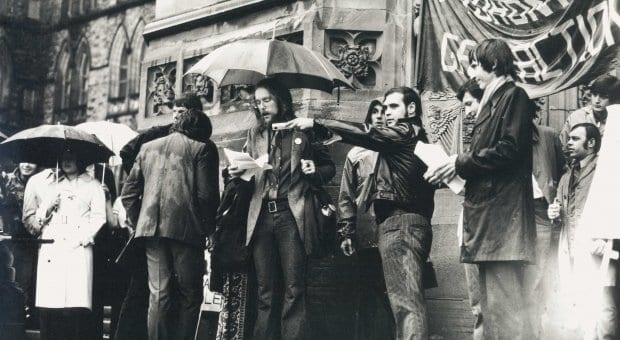

Charles Hill takes refuge under an umbrella while addressing demonstrators gathered Aug 28, 1971, on Parliament Hill. Credit: Xtra

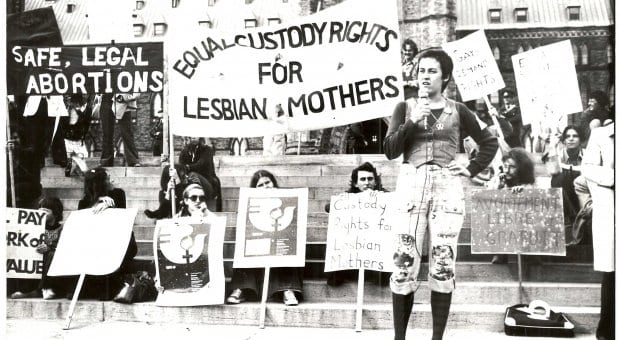

On Feb 19, 1977, lesbians and gays protested the CBC’s refusal to air public-service announcements for gay organizations. Credit: Xtra

Marie Robertson addresses an Oct 25, 1977, women’s rally on Parliament Hill. Credit: Xtra

In June 1975, Ottawa hosted the largest and most geographically diverse conference of gays and lesbians in Canada to date, with 200 delegates. Protesters confronted RCMP officers during a demonstration on Parliament Hill. Credit: Xtra

To celebrate Xtra’s 20 years of publishing to Ottawa’s gay and lesbian community, we’re digging through our archives to reprint a selection of noteworthy stories that highlight our community’s rich history. We begin the series with “Marching Forward,” which was published in June 1996 to mark the 25th anniversary of lesbian and gay activism in Ottawa.

Twenty-five years ago, a group of lesbian and gay Canadians decided to fight back.

Unlike the Stonewall riots, which galvanized the American struggle for lesbian and gay rights, there were no bottles thrown or windows shattered on Aug 28, 1971.

But in a smaller way, the first march on Parliament Hill symbolized the birth of the modern lesbian and gay movement in Canada and Ottawa. Until then, Ottawa had never been prominent in the struggle for lesbian and gay equality in Canada. Yet Ottawa certainly found its voice when nearly 100 young lesbians and gay men braved the pouring rain to announce their demands to Parliament. A precedent was established that would see Ottawa become the battlefield where politicians and judges would grant equal rights some day.

Much has been written about the struggle for lesbian and gay rights on Parliament Hill and in the Supreme Court, but less has been said about Ottawa’s local gay community, which many national activists called home and where a vital community was established in the shadow of Montreal and Toronto. Along with the warriors who fought the battle for gay rights on the national stage, there were dozens of women and men who created a proud community in our city. This is their story and all our victory.

Ottawa’s lesbian and gay community was long characterized by the political and historical conservatism of the Capital.

Author Gary Kinsman has just re-released his book The Regulation of Desire, which documents how the Canadian government regulated homosexuality. The latest version examines how early gay life in Canada has affected our communities today.

Kinsman says Ottawa’s lesbian and gay communities were heavily shaped by a series of national security campaigns conducted by the RCMP during the 1950s and 1960s.

In 1980, journalist John Sawatsky revealed a frightening period in Canada’s gay history, when he wrote about the infamous Fruit Machine, in his book Men in the Shadows. Carleton University psychology professor Robert Wake was commissioned by the federal government to build a machine that could detect homosexuals by measuring eye-pupil response to gay pornography. RCMP insiders jokingly dubbed it the Fruit Machine, and it never worked, partly because few heterosexuals volunteered to be control subjects, since they feared the machine might brand them as queer.

Canadian Press reporter Dan Beeby was among those who discovered that RCMP operatives snapped pictures, followed people and tried to force suspected homosexuals to list names of others.

“Any gay man or lesbian living in Ottawa, and particularly those who would have been in the military or the civil service, came under a lot of scrutiny,” Kinsman says. “The national security campaigns focused on lesbians and gay men as being a supposed national security risk, because of our alleged character weakness that made us vulnerable to blackmail and compromise by evil Soviet agents.”

RCMP agents were never too successful hunting for lesbians, but gay men provided them with years of amusement. Kinsman says RCMP agents even sat in the basement tavern of the Lord Elgin Hotel, one of Ottawa’s oldest gay hangouts, with newspapers in front of their faces, taking photographs of gay men through pre-cut holes in the paper. Hundreds lost their jobs and thousands had their names on lists and in files created by the Mounties. Stories of demotions, transfers and firings resonated in the minds of every lesbian and gay working in Ottawa.

RCMP investigations reached beyond the civil service. Research shows that non-government workers were followed, interrogated and suffered suspicious break-ins to their homes. Added to all the social fears of coming out, every queer man and woman had to face the real possibility of losing his or her job and facing a national security investigation.

The large networks of closeted men and women that existed in the Capital thrived at private dinner parties and weekend cottage gatherings.

Kinsman says many lesbian and gay civil servants would not even support community organizing, because they feared a visible gay presence might expose their own identities as queer people. These closeted men and women often left the repressiveness of Ottawa by escaping to friendlier places.

“For some people, one of their survival strategies in the ’60s was not to be gay or lesbian in Ottawa, but to be gay when they went on trips to Montreal or Toronto,” Kinsman says.

Today, many lesbian and gay Ottawans still escape on weekends to the larger and more developed gay villages of Montreal and Toronto. But Ottawa now boasts a community of its own, developed over the past 25 years.

A quarter century ago, Ottawa had few public spaces where lesbian and gay people could socialize. The lounges in the Lord Elgin Hotel served as Ottawa’s unofficial gay bars long before the Ottawa police officially permitted such establishments. Club Aquarius and The Coral Reef Club were among the first dedicated lesbian and gay bars.

At the time, Ontario’s liquor laws outlawed free-standing bars. Bars either had to be connected to a restaurant, which is why large hotels were popular sites, or they had to be run as private clubs.

The Coral Reef Club, jokingly nicknamed “The Oral Grief” by its detractors, was officially incorporated as a Caribbean club, though its lesbian and gay popularity quickly overshadowed any Jamaican connection. Originally a mixed men’s and women’s bar, The Coral Reef became a lesbian mainstay with its Friday night pubs.

“It’s been around so long that even 14-year-old girls in high school know if you’re a lesbian, you should go to The Coral Reef Club,” jokes activist and writer Heidi McDonell.

Hull was home to the Hotel Chez Henri, where prohibitions against same-sex dancing forced lesbian and gay couples to dance in groups.

Lesbian and gay life might have remained hidden behind closet doors today if it weren’t for the changes that swept across the American social landscape during the 1960s. The fight for black civil rights, women’s rights and finally lesbian and gay rights were ignited, and there was no turning back.

Not that Canada wasn’t progressive. Under a fashionable prime minister named Pierre Trudeau, the federal goverment decriminalized “homosexual acts” in 1969. But when it came to major history-changing events, Canada didn’t have a Stonewall, Kent State or Watts riot.

So it’s with considerable modesty that we say the modern era of gay Ottawa began during the second-last week of August 1971.

On Aug 21, the Gay Day committee of Toronto Gay Action (TGA) presented the federal government with a brief called We Demand, a list of 10 demands that included creating a uniform heterosexual and homosexual age of consent and allowing gays to serve in the military.

Seven days later, TGA members and supporters demonstrated in Ottawa. It was the first lesbian and gay march ever on Parliament Hill.

The rain kept pouring and the placards became so drenched that marchers had to drop their signs. A young graduate student named Charles Hill addressed the crowd that day and became forever immortalized in the photographs and film clips of the rally.

“It was a very joyful occasion; people were dancing,” Hill says. “It was the first time we had done something like that.”

The enthusiasm of the march called a small group of men in Ottawa to action. After all, it was pretty embarrassing that London, Guelph and Waterloo all had gay organizations, but the capital didn’t.

On Sept 14, 1971, seven men gathered at the home of Maurice Bélanger and Michael Black to form Ottawa’s first gay organization. On Oct 13, they adopted a name and began calling themselves Gays of Ottawa (GO), with Bélanger and Paul Wise as the two chairs of the group. The creation of GO would transform the way Ottawa’s lesbian and gay population lived, because it would establish a community. Finally there was a formal and accessible way to connect with others.

“Before then, you always had to know someone who was on the inside,” says Barry Deeprose, now president of Pink Triangle Services.

One of the first men to come out through Gays of Ottawa was David Garmaise, in 1972. Garmaise was a nice Jewish boy who grew up in a small town in Northern Quebec. He graduated McGill University and moved to Ottawa in 1968 for a job at the post office.

The conservative-looking Garmaise would frequently check out the gay pornography magazines at a dirty magazine shop on Bank Street. He never bought a magazine because he was too embarrassed to face the cashier. One day, mixed in among the covers of male flesh, he spotted a newspaper that would change his life.

It was a new publication from Toronto with a funny-sounding name, The Body Politic, Canada’s first national gay newspaper and the predecessor to the Xtra papers. In the middle of the newspaper was a listing of gay organizations across the country, including Gays of Ottawa, with meetings “every other week” at St George’s Anglican Church, on Metcalfe Street. Unfortunately, it never said which week the meetings were held.

The following Tuesday, Garmaise found the guts to show up at the church and staked out the entrance “for people who looked gay.”

“I saw some that looked effeminate … so I thought, ‘Hey, this must be the right Tuesday.’”

Garmaise entered the church and walked into a big meeting room, only to discover he was in an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting. Undeterred by his blunder, Garmaise found out the Gays of Ottawa meeting was down the hall. For the next eight years, he would join the ranks of Ottawa’s pioneering gay activists.

In August 1972, GO opened a centre on the sixth floor of Pestalozzi, on the corner of Chapel and Rideau streets. The building was a haven for social radicals of every colour, and GO members were delighted to find a landlord willing to rent space to homosexuals.

Ottawa’s early activists were mostly young people who were infused with the idealism of the hippie generation. Older gays and lesbians were annoyed by the “outlandish” youngsters who publicly proclaimed their sexual orientation and tried to organize formally.

GO started a speakers’ bureau and a telephone support line, aptly titled The Gayline, which now holds the distinction of being the second-oldest gay phone line in the world, after the one in New York City. One of the earliest GO creations was a community newsletter, which later evolved into Canada’s longest-running lesbian and gay publication, GO Info.

“It’s just a really incredible way of bringing together a community,” says Lloyd Plunkett, who spent years as GO Info’s production manager. “No community can really survive without a decent newspaper.”

Another early institution at GO were the community dances, which continued until recently.

“Dances were originally started as social situations, a way to stay out of bars, baths and bushes,” explains Jim Young, who served on the GO board during the mid-1980s and helped organize dances.

GO played an active role coordinating a growing national movement and hosted the first interprovincial conference of gay groups. Gay activists from Quebec City, Halifax, Toronto, Vancouver, Saskatoon and Montreal gathered May 19 to 20, 1973, and a federal election strategy was established.

In 1975, more than 200 delegates arrived in Ottawa for the third national gay conference, which at that time was the largest and most geographically diverse meeting of lesbians and gays in Canada. GO helped form an Ontario and National Gay Rights Coalition. The Ontario coalition still exists today as the Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights of Ontario. Ottawa’s early activists had the enviable task of simultaneously creating a local community and coordinating a national movement.

Based in Ottawa, GO members were frequently called on to wage the national battle for gay rights. On Oct 15, 1974, GO picketed the Immigration Department in protest of screening policies that discriminated against gays and lesbians who sought entry to Canada. The federal government ultimately changed its policy, after the immigration minister met with GO officials.

As the number of openly gay people increased in Ottawa, specialized programs and services sprung up. Ottawa’s first gay church opened on Sept 22, 1974, when the first Metropolitan Community Church service took place at the Club Private men’s bar.

While the earliest gay groups in Ottawa were run by men, an organized lesbian community was simultaneously growing within Ottawa’s already established feminist community.

Not every lesbian was satisfied in the feminist movement, which often closeted lesbians for fear that straight women would be scared off. Marie Robertson moved to town in 1975 and became one of the first female organizers in GO. Robertson was turned off by the prudish Ottawa Women’s Centre, which was popular with other lesbians at the time.

“There was a lot of political bullshit going on. If we were going to have a demonstration, they didn’t want to put the word ‘lesbian’ on a pamphlet.”

Robertson spent her early years at GO as one of the few lesbians willing to work with gay men. Her efforts as a tireless lobbyist, Gayline counsellor and educator won her the Lambda Foundation Award for Excellence in 1994.

Heidi McDonell came to Ottawa a few years later and joined the local feminist movement.

“You have to think of lesbian feminism,” explains McDonell, who later became a lesbian leader. “That was the biggest thing going as a political movement — which was separatist. And that’s why women were never involved with GO.”

Lesbians also faced different issues from gay men. Gay men had the privilege of being able to focus only on their sexual identities. Lesbians were busy demanding the most basic rights for their gender, such as equal pay. The invisibility of lesbianism made gay men the focus of most public attention surrounding homosexuality, and even in the mid-1970s, much of it was negative.

Around March 1975, gay men in Ottawa were getting nervous. In the preceding weeks, Ottawa police had begun holding news conferences to announce the names of men who had been arrested for using male prostitutes. The local news media faithfully published each suspect’s name and address, something they didn’t do for prostitution charges involving women.

The police further sensationalized matters by telling the media that they had uncovered a male prostitution “ring” and that many of the sex workers were juveniles, since the age of consent for gay sex was then 21.

GO president Charles Hill warned the editor of the Ottawa Citizen that a closeted man might kill himself if his name were published in the paper.

On St Patrick’s Day 1975, Ottawa’s newspapers published the names of four men charged with gross indecency, in connection with a so-called juvenile male prostitution ring. Hours later, the body of Warren Zufelt, a 34-year-old public servant, lay beside the 13-storey Chesterton Towers apartment building.

Activist and Gayline volunteer Denis LeBlanc recalls that Zufelt called the Gayline just days before he died and told the operator that he would kill himself if his name hit the newsstands.

Fifteen protesters from Gays of Ottawa picketed the offices of the Ottawa Journal and the Ottawa police. No more names were released to the media, and of the 16 men charged, none was ever sentenced to jail or given fines; they all received absolute discharges or suspended sentences. The events became known as the “vice-ring affair,” and the issues of outing and sensational coverage of homosexuality were first debated in the Capital’s newsrooms.

“It was a big turning point. The media and the police, even though they never really acknowledged it, realized they had made a huge mistake,” Plunkett says.

A month later, GO member Ron Dayman filed a complaint against the Ottawa Citizen with the Ontario Press Council, for biased reporting in the vice-ring affair. The entire affair laid a foundation for mistrust between Ottawa’s news media and the local gay community.

But for every loss, there was always a bittersweet victory. After presenting a formal request to be part of the 1975 Remembrance Day ceremony, LeBlanc and Robertson were given permission to lay a pink-triangle wreath during Canada’s official remembrance ceremonies. Their wreath commemorated the murder of thousands of gay men and lesbians in the Holocaust.

Another victory occurred in April 1976, when Ottawa city council voted to ban discrimination based on sexual orientation from its employment practices.

As damaging as the vice-ring affair was, local police continued organized assaults against the gay community. In May 1976, The Club Baths at 1069 Wellington St was raided by Ottawa police. Nearly every Ottawa activist was attending a lesbian and gay rights conference in Kingston that weekend. Hearing news of the raid, members of GO wrote a press release, drove back to Ottawa, and read their statement on the 11 o’clock news.

The organized community response to the raids, including assistance to arrested men, would form a model that Toronto’s gay community leaders used when its baths were forcefully raided by police in 1981.

Baths, washrooms and parks within a two-hour radius of Montreal were raided that summer as part of a clean-up operation for the 1976 Summer Olympic Games in Montreal.

During that summer, Marie Robertson rounded up her friends and along with Rose Stanton founded Lesbians of Ottawa Now (LOON), the city’s first lesbian organization.

As lesbian activism gained momentum in Ottawa, Robertson got a mysterious phone call one day from a high-ranking Secretary of State employee. The female caller refused to talk over the phone and insisted on a personal meeting. At a café, the mysterious woman claimed that the Canadian government was feeling threatened by the emergence of a lesbian movement and that her group was being watched.

In the bars, men and women continued to share stories of RCMP investigations and job dismissals. Even after such incidents ceased by the late 1970s, the rumours and legends persisted, but it didn’t matter because there was too much momentum to stop the movement.

Ottawa’s lesbian community continued to grow during the late 1970s. In the fall of 1977, cable viewers saw lesbian and gay community programs on Ottawa’s Skyline Cablevision and Hull’s Telecable Laurentien.

Male Homophiles Anonymous was established by a group of gay men in Ottawa who felt GO was too political. Barry Deeprose, who later joined the “radicals” at GO and became an AIDS activist, was a member of this society for closeted men and recalls the overly cautious nature of their secret Friday night meetings. The “secret society” was a stark contrast to the hundreds of lesbians and gays who were dancing and drinking each Friday night in gay bars in Ottawa and across the river in Hull.

The changes that occurred during the first decade of Ottawa’s organized lesbian and gay communities were unbelievable. But it all went up in flames on the night of Feb 16, 1979. A fire destroyed the GO Centre at 378 Elgin St, and all the paperwork from that first decade was burned away.

About 10 people were in the building that night, attending a Friday night drop-in. They quickly evacuated the building and watched the city’s gay community centre burn. GO eventually moved to a home at 175 Lisgar St, and finally to 318 Lisgar.

The GO Centre had served as the national coordinating office of the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Rights Coalition, and GO members worked hard after the fire to stage the 1979 Celebration conference, which drew the largest national assembly ever of Canadian lesbian and gay groups. But that conference was the last truly national meeting of lesbian and gay groups in Canada. Ottawa’s role as a national focus point for lesbian and gay activism began to dwindle after the 1970s. Victories at the provincial level convinced many activists to alter their strategies and spend less time trying to win a national battle and more time trying to score provincial gains.

With this political shift came new developments at GO. For years, LOON had rented space from GO for its social events, and now LOON members were migrating to Gays of Ottawa.

“Through the late ’70s and into the ’80s we had done enough work on our own, separate as lesbians, that we felt we could integrate back with the men,” Marie Robertson explains.

In the 1990 anthology Lesbians in Canada, activist Carmen Paquette writes about the history of lesbian separatism in Ottawa and how GO developed a reputation as a group where lesbians and their concerns were taken seriously.

The separation between Ottawa’s lesbian and gay communities was bridged during the 1980s, as Gays of Ottawa attracted more women to its dances and large numbers of women bought memberships with GO. Gays of Ottawa became a truly co-sexual organization, with women increasingly occupying important and powerful roles. Later, the loss of many gay men to AIDS and AIDS activism opened even more positions for women.

McDonell says Ottawa’s smaller size forced men and women to work together.

“Ottawa is actually kind of different than most places. A lot of places, gay men and lesbians work together a lot less in organizations. The only reason they worked together so much in Ottawa is because in the end they only had this one space. They sort of shared it.”

Robertson admits there were splits between men and women.

“We had some pretty dirty fights … [But] I always found the men at Gays of Ottawa willing to take that leap of faith to understand a particular [women’s] issue.”

Along with changes in the women’s community, a new era of openness had also convinced many men and women who were closeted throughout the 1970s to come out in the 1980s. People who had refused to sign cheques to GO and used assumed names in the bars were coming out to their families and co-workers. Civil servants and private sector employees who had previously concealed their lovers and their weekends were now living proud lives in workplaces across the region.

Ottawa’s media was also beginning a new era of openness. In June 1980, the Ottawa Citizen published a special series on Ottawa’s lesbian and gay community. Reporter Richard Labonté came out to readers in a personal essay, and two other reporters took readers into the world of bathhouses and cruising parks. Many lesbians were annoyed because the articles focused on gay male promiscuity and ignored the reality of their lives, while some gay men feared the stories would increase bashings.

As the invisibility of Ottawa’s lesbian and gay life faded away, so did the landmarks. In response, in the spring of 1981, the Lord Elgin Hotel decided to start closing the downstairs tavern at 3pm each day, effectively shutting down Ottawa’s oldest gay bar. Patrons never forgot “John the waiter” — a married straight man who had served drinks to Ottawa’s gay community since the 1950s.

There was a new sense of optimism, which led many to believe that gays and lesbians were truly liberated. But as difficult as the struggle for lesbian and gay rights had been in the previous decade, few activists could have ever imagined the tribulation that one microscopic virus would unleash in the years ahead.

Barry Deeprose, who had long abandoned Male Homophiles Anonymous, was working as a Gayline volunteer at the time. One night in July 1981, he discovered an unusual article posted on the Gayline notice board. It was a story from The New York Times about a rare cancer that had been discovered in gay men.

“I had the sense that something dreadful had gone wrong,” Deeprose says.

Slowly the trickle of information grew, but no one thought the plague would touch Ottawa. At first, local gay men tried rationalizing that it was an American problem, then when doctors in Montreal and Toronto began diagnosing cases, many Ottawa men said it was a big-city problem. It would be only a few months before local men began experiencing their first symptoms.

The full involvement of women in GO became a reality later in 1982, as GO elected a 27-year-old chemist named Linda Wilson as its first female president and passed a bylaw that mandated equal representation between men and women on the board. A proposal to change Gays of Ottawa’s name, to make it friendlier to women, was defeated mostly by women, who said the name GO had a credible reputation in the community.

Women leaders would hold more important positions as the ranks of Ottawa’s male leaders were depleted by volunteer burnout and AIDS. By the end of the decade, GO would become largely a women’s organization.

Outreach to francophones was another goal of GO. In other cities, ethnic differences were racially visible, but in Ottawa, language formed the major ethnocultural divide. From its early days, GO tried to release all its printed materials in both official languages, and for many years the group’s official title was Gays of Ottawa/Gais de l’Outaouais, a token gesture that acknowledged that many local gays and lesbians weren’t anglophones.

By 1982, the Gayline was flooded with desperate callers seeking information about AIDS. Unsure operators told callers to shower before sex and avoid sex with people who had skin lesions.

“People would be calling us to find out symptoms; people would be calling us with symptoms,” Deeprose says.

In August, GO held a public meeting with officials from Health and Welfare Canada’s Laboratory Centre for Disease Control. Seventy people showed up to hear what little information the scientists knew.

Meanwhile, the women’s community was growing. Ottawa’s first feminist bookstore opened in September 1982. Mayor Marion Dewar cut the pink ribbon at the Ottawa Women’s Bookstore. It was a time when the mayor of Ottawa was sincerely supportive of the lesbian and gay community.

When 1983 rolled around, major changes were in store for Ottawa’s lesbian and gay community. In order to gain charitable tax status, GO decided to split its social service efforts and create a new organization, Pink Triangle Services (PTS). That decision would ultimately weaken Gays of Ottawa, by taking away its core functions.

But the future survival of Ottawa’s lesbian and gay organizations was less important at a time when the survival of the city’s gay men was in question.

Another emergency community meeting on AIDS drew a packed house at the GO Centre. A Dr Jessamine, from the federal Centre for Disease Control, provided some of the first reliable information about AIDS.

“We had people standing in the hallways. They couldn’t even see the speaker,” says GO activist Lloyd Plunkett. “People were really scared and wanted to know what was happening.”

On Jan 7, 1984, Ottawa mourned the death of Peter Evans, our first recorded AIDS casualty. He died at the Ottawa General Hospital, which soon became the region’s AIDS treatment hospital.

Gay men were especially targeted during the early years of the AIDS epidemic.

Ottawa evangelist Bill Prankard fuelled the AIDS hysteria by launching a campaign to close the Club Baths, along with most of the city’s gay institutions, including the GO Centre.

More than 100 Carleton University students held a rally after the mural advertising Gay People at Carleton was defaced with swastikas and slogans such as “kill fags.”

But the hatred was not limited to gay men at the time. Ottawa city alderman Rhéal Robert created a controversy when he called GO Info “dirty and filthy” at a council meeting, on March 7, 1984. He was upset by a poem about female oral sex, written by Marie Robertson in the previous issue of GO Info. Robert didn’t want the city of Ottawa to advertise in the paper and asked the Ottawa police morality division to lay obscenity charges against GO Info.

CJOH-TV reporter Jim O’Connell sensationalized the issue in a report where he told viewers he couldn’t show a copy of GO Info on the air, then showed a close-up of a GO Info ad for Gaymates, a mail-in dating service. “We all know the kind of recreation that these people are really interested in,” chirped O’Connell, who was later promoted to CTV’s Washington bureau.

Other homophobic media figures included Dean Tower, who hosted a call-in show on CFRA radio and later on CHRO-TV. Tower verbally attacked gays and lesbians on the air and hung up when they called his radio show. Readers of the Ottawa Citizen would later be subjected to the homophobic opinions of columnist Claire Hoy.

One of the saddest chapters in Ottawa’s lesbian and gay history ended in 1984, when Solicitor General Robert Kaplan sent a letter to NDP MP Svend Robinson confirming that all the old RCMP files on suspected homosexuals in the civil service and elsewhere had been burned, pulped or electronically erased. Although the government no longer ruined the careers of gays and lesbians, the fear of coming out still remained after years of purges. Robinson himself remained closeted for another three years.

The fall of 1985 brought a municipal election in which activist Denis LeBlanc ran as an openly gay candidate. LeBlanc lost, but a then-closeted man named Mark Maloney won another seat and became a strong advocate for local gays and lesbians, along with fellow council member Diane Holmes.

Just as Gays of Ottawa had created offspring groups, so did PTS. The AIDS Committee of Ottawa (ACO) was founded on July 9, 1985, at a PTS board meeting, when Barry Deeprose proposed the creation of an AIDS committee. Board member Bob Read agreed to join the newly formed committee, which later split off and became its own entity. In the early years, Deeprose established a buddy program modelled after the innovative system developed by the New York Gay Men’s Health Crisis, and Read began the prevention and education effort. Other early AIDS organizers included Sally Eaton and Ron Bergeron.

Later that year, the first AIDS test became available, and many people who thought they were safe discovered that they had the AIDS virus.

After a long period of inaction on the federal front, new momentum began on Parliament Hill. In October 1985, the all-party parliamentary sub-committee for equal rights agreed that discrimination against lesbians and gays should be prohibited.

A group in Ottawa decided to get the ball rolling by staging a national letter-writing campaign, and after hundreds of letters poured in, the Equality Writes Ad Hoc Committee (EWAC) found a better name. Within a year, Equality for Gays And Lesbians Everywhere (EGALE) was formed by Heidi McDonell, Les McAfee and Caroll Holland to lobby Parliament for lesbian and gay rights.

At the provincial level, Ottawa Centre MPP Evelyn Gigantes scored a victory for all gays and lesbians across the province when she got the Ontario legislature to amend the Ontario Human Rights Code to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation. A decade later, she would face criticism from local activists when her party, then in power, allowed a free vote on lesbian and gay rights and lost the vote.

In May 1986, a gay student named Oscar at Gloucester High School came out to the student body in a letter to the school newspaper. Many students were outraged, and a petition was sent to the principal. The letter from Oscar was one of many courageous acts in which gay, lesbian and bisexual students were coming out in Ottawa.

In 1987, for the first time in history, lesbianism was specifically mentioned in the House of Commons during a speech by Toronto MP John Oostrom, who was upset that lesbian events were being funded by the government, as part of Ottawa’s International Women’s Week.

The previous year’s International Women’s Week had brought many lesbians together, and the momentum of that year’s workshops helped form Lesbian Amazons, a radical lesbian collective that helped spawn Ottawa’s first-ever International Lesbian Week.

During the late 1980s, lesbians became increasingly visible within the women’s movement. Groups such as REAL Women were part of an organized backlash that formed not so much to oppose the power that women were gaining, but to oppose the visibility that radical lesbians were gaining in the women’s movement. Many conservative women felt their image of womanhood was threatened by lesbians and pro-choice advocates.

On the AIDS front, new education programs were being created to teach “the new facts of life.” Young people got a new comic hero when ACO unveiled its Captain Condom brochures, designed to teach safer-sex practices through humour.

But there weren’t too many smiles from local politicians. Regional chair Andy Haydon told local AIDS activists on Oct 16, 1987, that he wouldn’t support funding for AIDS programs because it affected a specific group; he later advocated compulsory AIDS testing for all the region’s employees.

As time passed, governments eventually decided that AIDS services needed public funding. In November, the provincial government gave $232,000 to ACO, and Grant MacNeil was hired as an interim executive director, later to be replaced by David Hoe.

By 1988, the AIDS crisis had erupted in Ottawa. People were getting sick and dying. ACO hired five employees to manage its growing services, and Bruce House was established to assist people with AIDS find housing.

As local gay men wondered if their government really cared, after a slow response to AIDS, lesbians, too, felt the government didn’t care for them in 1989 when the government awarded a $21,212 grant to REAL Women, a group that criticized lesbians. Protesters from Lesbian and Gay Youth of Ottawa/Hull lined the front of a REAL Women conference in April, along with local feminists.

The summer of 1989 was an important period in the development of Ottawa’s lesbian and gay community. It was the summer when a lot of straight people in Ottawa learned what homophobia was all about. It also taught the lesbian and gay community that silence equalled death.

Male cruising and park sex had occurred around the grounds of Parliament Hill and Major’s Hill Park since the days of Confederation. As awareness of these settings crossed over to the heterosexual world, the danger to men in the parks increased. Every couple of years, the pages of Ottawa’s newspapers reported another man mysteriously murdered in the city’s parks. Years of police harassment in Ottawa’s gay bars and parks had left its mark on the community. Many gays and lesbians didn’t trust the police.

In the summer of 1989, the Ottawa Citizen reported an unusual number of stories about men who had “fallen” off the rocks near Major’s Hill Park. Like other gay men in town, gay activist David Pepper knew what was going on.

By summer’s end, three men were dead and another four suffered injuries resulting from falls. Local politicians were puzzled as to why so many men were frequenting the park late at night and why they kept plunging to their deaths. National Capital Commission officials responded by reinforcing the railings along the trails. Pepper responded by alerting his friends in the gay community.

But it took a bloody night of terror to wake up the police and local media to the reality of homophobic violence.

On Aug 22, 1989, the badly beaten body of a Château Laurier waiter named Alain Brosseau was found floating toward the Hull shore. During the previous 24-hour period, a gay couple in Orleans awoke at 4am and found a gang of young men who had just broken into their home. Alain Fortin was stabbed in the eye and hand. His throat was slashed and his back was sliced five times. His partner, Wilfred Gauthier, ended up with a perforated intestine and a three-inch cut to his throat, which permanently damaged his vocal cords. Both men survived to testify against the men who nearly killed them.

As the police investigated the attack on the couple in Orleans, a startling connection was made between the house beating and the murder of Alain Brosseau.

According to the testimony of the youngest assailant, a 16-year-old who became a crown witness, he and three friends went looking for a gay man to beat up for cash. The first gay man they attacked managed to escape onto Sussex Drive with a stab wound. Their next victim was Alain Brosseau, a waiter walking through the park on his way home to Hull. The young gang ended their night of terror with a cab ride to the address of a gay man they had mugged a week before — the home of Fortin and Gauthier.

On the Interprovincial Bridge, Brosseau was robbed, beaten and then thrown off the bridge to his death by Jeffrey Lalonde, 18, Thomas MacDougall, 18, Duane Martin, 17, and the 16-year-old, whose name was withheld. The victim’s family emphasized the irony that Brosseau was straight.

It was the final straw for local activists. For years, Ottawa police had not been protecting the gay community from homophobic violence. Pepper began organizing a campaign to improve the safety of Ottawa’s gay community. Meanwhile, a Carleton University student named Pierre Baulne was grabbing the headlines of local papers, trying to voice his plea for better police protection and facing ridicule from gay men who scoffed at his suggestion that gay people wear whistles. During the Brosseau murder trial, accused killer Thomas MacDougall said the gang was out “to roll a queer.”

Lalonde got a life sentence for throwing Brosseau off the bridge, plus 10 years for the Orleans assault; Martin got eight years; MacDougall got seven years; and the 16-year-old got a suspended sentence for helping the Crown convict his friends. Two other accomplices in the Orleans attack also received sentences for stabbing the men and breaking into the home.

But Ottawa police kept silent, and two years later, local politicians had forgotten the issue. But some in the media who covered the Brosseau murder didn’t forget. CBC radio host Jennifer Fry decided to do a follow-up piece on her show. David Pepper was among a panel of guests who lamented that nothing had been done.

Ottawa Councillor Mark Maloney was listening to the radio that day and was disturbed that police had not made an effort to curb hate crime in Ottawa. As one of several closeted gay politicians at the time, Maloney decided to take a stance and helped organize a meeting between local gay activists and the police advisory committee in July 1991.

The group continued meeting, and in 1993 the Ottawa police created a bias crime unit to investigate and educate the community about hate crime.

Two years later, Pepper was hired by Police Chief Brian Ford as his special assistant, based on the leadership and community organizing skills Pepper had showed in his four-year campaign to improve safety for gay men and women in Ottawa.

While that summer left a painful scar on the community, the tragedy of AIDS had left even deeper wounds. Thousands reflected on those losses by viewing the Names Project AIDS Memorial Quilt, which came to the Capital during the 1989 Pride Week.

In 1990, an HIV-positive ACO board member named Don Walker opened the People Living with AIDS Centre, which later became The Living Room, a drop-in for people affected by HIV and AIDS.

A francophone ACO board member named André Lemieux founded the Bureau Régional d’Action SIDA (BRAS) later that year, to provide AIDS services in the Outaouais.

As the organized lesbian and gay community ended its second decade, there were major changes in store for the city’s oldest gay organization. In June 1989, Gays of Ottawa changed its name to the Association of Lesbians and Gays of Ottawa (ALGO). There was also increasing tension between ALGO and its newspaper, GO Info.

Members of the paper were seeking editorial autonomy, while the ALGO board felt the paper should reflect the position of the association. A series of fights eventually ended with the resignation of many contributors.

At city hall the mood was cautious. In the spring of 1990, local activists asked the city to proclaim Lesbian and Gay Pride Day and council agreed, until they discovered it coincided with Father’s Day. Many local politicians said it was insulting to have the two events on the same day, and the proclamation was defeated. A year later, when Pride wasn’t on Father’s Day, Ottawa city council agreed to the proclamation.

By 1991, Ottawa had its very own chapter of Queer Nation, a controversial militant lesbian and gay group that advocated outing and public kiss-ins. Pepper’s, a restaurant on Elgin Street, was targeted for a kiss-in demonstration after an affectionate gay couple was scorned by the restaurant manager.

But the heyday of local activism was pretty well dead; Queer Nation quickly lost its momentum. Much of the enthusiasm that had driven the activists of earlier years had disappeared with the growth and increasing acceptance of gays and lesbian in town.

One of the early signs that ALGO had lost its purpose was the clash between the ALGO board and GO Info staff. In 1993, GO Info suspended publication, and in the skirmish, Toronto’s Pink Triangle Press entered the Ottawa market with its latest publication, Capital Xtra. The emergence of a competing paper was a heavy blow to GO Info, which began publishing again but as a smaller paper.

As the old guard of lesbian and gay activists became too burned out to lead their community, a new generation was ready for action. In 1993, an ambitious Kanata city councillor named Alex Munter became the darling of the local scene when he became the first local politician to come out. Munter was one of several prominent Ottawa figures who were outed that year in Frank magazine, the satirical gossip rag.

“I was completely out in my personal life, yet there was a level of ambiguity in my public life,” Munter explains.

In 1993, the Association of Lesbians and Gays of Ottawa added the word bisexual to its title but decided to keep the acronym ALGO; it was eventually changed to ALGBO.

The debate over adding the word bisexual included a lot of bitterness. Kerry Beckett, then president of the battered organization, said the poisoned mood that resulted from the bisexual debate led to the group’s ultimate demise.

By the fall of 1994, ALGBO was in financial trouble. A $12,000 budget deficit and the larger question of ALGBO’s purpose loomed over the heads of a continually shrinking board. Over the years, the original GO organization gave birth to PTS, ACO and the Abiwin Housing Co-op. By the 1990s, there was little for the mother organization to do. The board members themselves were unable to develop successful survival strategies. For years the women’s dances kept ALGBO going, but as heavy drinking declined, so did the profits.

In the spring of 1995, Ottawa city council was again debating Pride Day. This time, the controversy stemmed from the inclusion of the words “bisexual and transgendered” in the title of Ottawa’s Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Pride Day. Council finally agreed to call it simply Pride Day.

After years of impending doom, ALGBO finally gave up. In September 1995, Beckett and her board suspended the operations of the organization, after the group had accumulated a $16,000 debt. In November the board vowed to pay off all debts and keep a mailbox, leaving hope for a future revival.

Ottawa’s lesbian and gay communities had outgrown the existence of one small organization, and in many ways the death of ALGBO symbolized the growth and success of Ottawa’s lesbian and gay population.

One of the oldest institutions in the community died a death that went largely unnoticed by most of its citizens because there were more than 50 support and social venues for gays and lesbians in Ottawa.

“I don’t think anyone in 1971 would have predicted where we would be today in terms of power and influence,” says Barry Deeprose, who was saddened by the loss of ALGBO, while hopeful of the community’s future.

Activists like Heidi McDonell are amazed at how many people have come out in Ottawa over the last 25 years.

“There was this culture of closetedness that was always in Ottawa. So people in general weren’t as open. It used to be hard, even in 1982, to find people who would be willing to go on TV or radio,” McDonell says. “That’s the biggest difference — the willingness of just everyday gay people, normal people — who maybe aren’t political, just to be visible.”

There are many lessons that have been learned by our community in 25 years. The importance of visibility is a concept shared by all our community leaders.

As we celebrate the 25th anniversary of organized lesbian and gay communities in Ottawa, we pay tribute to our proud history. The names of men and women in this essay reveal only a fraction of the countless pioneers who built our community, some of whom have been lost in faded memories.

As John Duggan, one of the community’s earliest leaders, said when asked why so few records exist of those early years, “It didn’t occur to any of us at the time that any of this would be of importance.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra