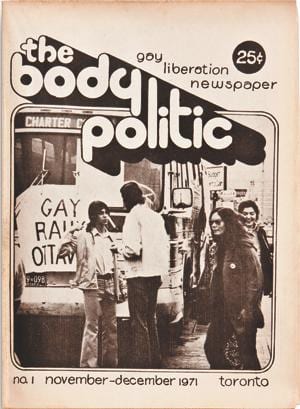

A photo of the We Demand protest was reproduced on the cover of the first issue of The Body Politic. Credit: Ryan Faubert; Cover photo by Jearld Moldenhauer

Credit: Ryan Faubert; Cover photo by Jearld Moldenhauer

They were making history, even if they didn’t know it at the time.

Forty years ago, a group of politically minded gay men and women from Toronto travelled to Parliament Hill in Ottawa to present a list of demands to the Canadian federal government.

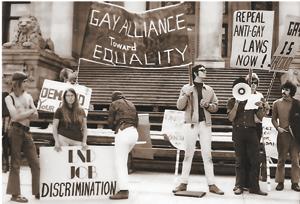

In Vancouver, a smaller group of 20 held a parallel demonstration in Robson Square, reading from the same demand list on the steps of the then-courthouse.

Their 10-point list asked for an end to state-legislated discrimination against gays.

According to many, it was the first time Canadians had protested publicly for gay rights.

“It was the weekend; there was no one in the building. An RCMP officer was our sole audience. An American war protester got hold of our microphone and started haranguing us, the world at large and the United States Congress,” George Hislop told Xtra in 2001, recalling the Ottawa protest. “It didn’t last very long, but it made the six o’clock news, and that was the point… We were proposing social revolution.”

The pouring rain in Ottawa didn’t deter the protesters, who had set the date to coincide with the second anniversary of the decriminalization of gay sex.

How many attended the Ottawa demonstration is up for debate. The number fluctuates from 100 to 200, depending on who you ask.

“In those days people would exaggerate the numbers on our sides and the cops or the opposition would underplay them, but I say there was only about 100 of us. We knew it would be small, but we felt it was important,” says Brian Waite.

At the time, the 27-year-old Waite was a member of Toronto Gay Action, which started out as a part of the Community Homophile Association of Toronto (CHAT) but eventually splintered off.

“There was a vote. Anyone who was at these meetings could vote, and we were voted out. Many of the gays then were still conservative,” Waite explains. “They didn’t have any legal rights, so they tended to be more conservative.

“Us more politically activist-oriented types, we wanted to get into public demonstrations, which was a bit of a brave step; people could lose their jobs, be beaten up and so on,” he says. “The vast majority of the leadership and activists of the gay movement in the early ’70s were already radicals.”

They came from all sides of the left, he says: the anti-war movement, the women’s liberation movement, Americans fighting for free speech in Berkeley and black civil rights in the US, the Communist Party and leftwing New Democrats.

“Essentially, once we came out, nothing could be more natural than for us to start organizing for our own liberation,” Waite says.

Many of the men and women who were at that first public protest, and continued to play parts in the gay movement, have since died, taking their memories of that day with them. Herb Spiers, who coauthored the list of demands, passed away in March. George Hislop, who cofounded CHAT in 1971, died in October 2005.

Others who were there say they don’t remember that particular event and that it wasn’t something that stuck out to them at the time.

Roedy Green was 23 and an active member of the Gay Alliance Toward Equality (GATE), a Vancouver gay liberation group.

“It was just one of hundreds of things that we did. I don’t remember it particularly as being one of the biggies,” says Green. “This is something that the people who were not there, I think, have created.”

Author Stan Persky was involved with GATE, but the Vancouver August demonstration doesn’t stick out for him, either. “I have a very vague memory of it, but I don’t remember if I was at the demonstration or not,” he says.

Though Green doesn’t recall the specific day, he does remember some of the contemporary protests at Robson Square.

“You’d take out your megaphones and banners and try to attract a small crowd,” he says.

“There was no internet. If you were really lucky you’d attract some newspaper reporters who would come, and you would hand out mimeographed sheets about whatever it was you were saying.”

“We weren’t a very big group [GATE], only about 20 people at most. We were considered really crazy people, and people were quite angry with us, because we were going to get everybody killed,” he continues.

“From the point of view of the average gay person, the closet was the safest place. If people didn’t know you existed they couldn’t very well come out and kill you.”

Before Green met his first gay person in 1969, he thought he was the only one. “It just gives you an idea of how completely hidden everything was.”

Ed Jackson was part of CHAT but missed Ottawa’s August demonstration by a few weeks. He had been travelling abroad in Europe and returned to Toronto in September 1971.

“I came quickly after it, but I was not in attendance,” says Jackson, who was 26 at the time.

Jackson doesn’t recall people recognizing the significance of the event at the time. He says they were too busy pushing for action. Their message didn’t get as much media attention as they’d hoped, so they pushed to create their own publication: The Body Politic (Xtra’s parent publication).

“This [was] totally in the midst of a time where there was the black civil rights movement, there was the feminism, there was the whole idea that the world can change.

“A lot of the people I’ve talked to became veterans of demonstrations, and all the demonstrations flew one into the other,” says Jackson. “They just wanted to be treated equally. They wanted to reduce the kind of stigma and discrimination and police harassment that they were experiencing.”

This August, Brian Waite, Ed Jackson and Roedy Green will be on a round-table panel at the We Demand conference in Vancouver (see sidebar), discussing their experiences in the early days of the modern gay liberation movement.

Jackson remembers realizing the significance of August 28, 1971, a decade later, when he was writing a historical piece looking back at the original protest.

“At that time, I don’t think any of the demands had been achieved, in 1981, but they soon started one by one,” he muses.

Looking at them now, he recognizes that not all of the demands were realized, but he attributes that to the vague nature of some of the requests for systemic change.

“More or less, though, the main demands have all been met,” he says.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra