Brian Chittock Credit: Audrey McKinnon

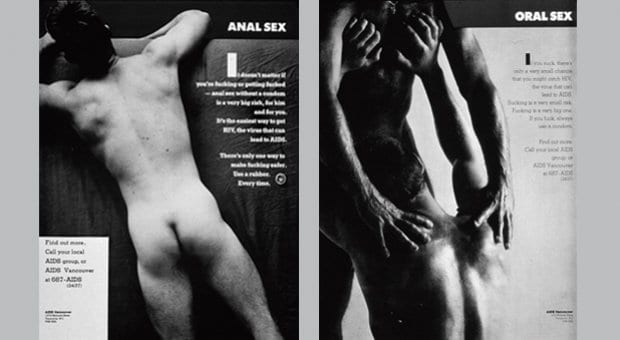

Early AIDS Vancouver posters from the 1980s. Credit: Courtesy of AIDS Vancouver

“We kind of lost our way,” says AIDS Vancouver executive director Brian Chittock.

AIDS Vancouver’s focus has become a bit vague since half a dozen gay men founded it in 1981, he explains. “We didn’t know what direction we were supposed to go into and how to really accommodate everyone.”

While Chittock says AIDS Vancouver’s main clientele is still gay men, the organization now serves all HIV-positive people who call or walk through the door at 1107 Seymour St.

“The group that we’ve ended up serving the most of is the people who have suffered from HIV in the most difficult way, who are the poorest of the poor, who may be homeless, who may be using drugs or not,” Chittock says. “It doesn’t really matter; it’s just kind of that group that nobody seems to want to do anything with. And we’re the last ones that are serving that group of people.”

It may be a demographic desperately in need of assistance, but it’s a far cry from the organization’s original mandate.

“It started in my living room, my partner’s living room,” says Gordon Price, one of AIDS Vancouver’s six founders. “And it was at that meeting we decided, at the minimum, what we should do is hold a public meeting at the West End Community Centre.”

Price, who five years later would became a city councillor, remembers it was one friend in particular, Ron Alexander, who galvanized the group into action.

“Ron was really pissed. I mean, why aren’t we paying attention to what’s going on out there?” Price says. “I had no choice but to agree with him.”

Price had been subscribing to the New York Native, a biweekly gay magazine. The magazine was the first to report on what was then rumoured to be a “gay cancer.”

Medical writer Lawrence D Mass wrote the article titled “Disease Rumors Largely Unfounded,” published on May 18, 1981. He wrote: “Last week there were rumors that an exotic new disease had hit the gay community in New York. Here are the facts: … The organism is not exotic; in fact, it’s ubiquitous. But most of us have a natural or easily acquired immunity.”

“My recollection is there was really no name for it, because sometimes it was referenced as the indicator diseases, like pneumonia,” Price says.

At the time, there were six cases of the mysterious disease in Vancouver. While that number seems tiny compared to today’s infection rates, Price and his cohorts knew they had cause for concern.

“I think we actually had a kind of chart. It was very sketchy; it was basically just a line going up. But it was almost dead on in terms of infection rates,” Price says.

“It was damned scary. We’d even get into some rather apocalyptic scenarios, particularly around quarantine. I mean, you couldn’t rule that out.”

Price feared the “ill-informed hysteria” that could come out of the nameless disease. “Our job was really to try and get the word out about what we did know and what action or prevention you could take.”

“We didn’t want to give a blanket condemnation — ‘Don’t have sex’ isn’t going to apply. So we had to give, as much as we could, advice on what was known and what action, what degree of risk you could take,” Price recalls.

In those early days, the mysterious disease was thought to affect four groups. Those groups were described as the “the four ‘H’s,” which stood for Haitians, hemophiliacs, heroin users and homosexuals. Price says AIDS Vancouver focused on the homosexual “H” because, unlike Haitians, the demographic was relevant to Vancouver and, unlike hemophiliacs, it had no existing support group. And, of course, homosexuals were familiar to the founders of AIDS Vancouver.

So the six founding members got to work, trying to spread what little knowledge was available within the gay community. Two years later, they registered their organization as a non-profit society to apply for government funding.

The first thing they did was commission a brochure. Price’s enthusiasm is still palpable as he recalls its production. “It was hot! We used sex to give people advice on sex.”

When the health minister once pulled out a brochure and asked, “Are you responsible for this?” Price shrugged it off. “It wasn’t meant for, well, someone like him,” he says.

Chittock misses those in-your-face brochures.

“We’ve become politically correct,” he laments. “You know, when we had that kind of in-your-face prevention going on and it was public, we saw reductions in the number of new infections.”

He remembers one poster from the early 1980s that showed a man giving oral sex to another man, explaining the different risks of oral sex compared to anal sex. Another poster shows a naked man, face down, and says, “It doesn’t matter if you’re fucking or getting fucked — anal sex without a condom is a very big risk, for him and for you.”

The shift away from such direct messaging extends beyond AIDS Vancouver, Chittock says.

“The movement has become more polite, politically correct. It’s changed over the years because of the change in the direction HIV has taken.”

But polite prevention programs that target everyone generally don’t work, Chittock warns.

Even getting polite prevention messages to certain cultural groups can be challenging, he notes, pointing, for example, to Chinese men who have sex with men. “That’s a taboo topic within the Chinese community. They don’t want to talk about sex, they don’t want to talk about HIV, they don’t want to talk about sexual transmission. All those key areas are what we need to help break down in a lot of those ethnic communities,” he says.

“If we have people focused on going into those specific communities and training people around HIV prevention in their own languages as well, we’ll see some breakthroughs. We know that,” he states. “We just haven’t been able to get the money to do it.”

The provincial government — one of AIDS Vancouver’s two main funders through the Vancouver Coastal Health Authority — recently cut funding to the organization’s last prevention-worker position, leaving it ill-equipped and under-resourced to do much, if any, prevention work on its own.

The little prevention work it still does is now geared toward educators and community organizers to teach them about issues related to HIV/AIDS in a workshop that says very little about gay needs.

No surprise that, as AIDS Vancouver broadened its focus away from its original core constituency, other gay groups emerged to take its place.

Man2Man began as a subgroup of AIDS Vancouver before branching out on its own.

“A program like Man2Man was in the bar on a regular basis,” says Phillip Banks, who worked with AIDS Vancouver from 1995 until 2003. “There were guys out there handing out condoms on a regular basis. They were in the bathhouses; they were going to house parties. They were going wherever they could go to reach gay guys.”

Banks joined AIDS Vancouver as its connection to the gay community was beginning to weaken. He attributes this in part to gay men’s condom fatigue — a decade worth of rubbers with reminders.

At the same time, he says, some people within the organization believed the gay community was abandoning them. “It was a relationship issue. But you don’t see that when you’re in it,” Banks says.

“More and more, even HIV-positive gay guys were seeing that the gay-friendly space in the building was becoming a bit less gay-friendly because the organizations in there were appealing to a broader demographic now,” he says.

Besides HIV, the affected groups often had little in common. The gay clientele did not get along with the intravenous drug users, for example, Chittock says.

“The two did not want to be together. Which is not that unusual because it’s happened over and over again in the history of HIV with different groups. It happened the same way with the blood transfusion group. They didn’t want to be with the gay people either. Nor did they want to be with the IDU people,” Chittock says.

In 2002, Man2Man became Gayway and, steered by Banks, it broke off from AIDS Vancouver.

“The organization, I think they just realized gay men needed more and they couldn’t do it,” Banks says.

Gayway (now called the Health Initiative for Men) was conceived to focus on gay men’s health holistically, addressing HIV even as it nurtured general wellness, both physical and emotional.

As AIDS Vancouver celebrates 30 years this July as a registered non-profit society, Chittock would like to diversify its funding base to broaden its programming.

“Where we’re trying to go is to broaden our funding base so that we’re not reliant on one major funder, which we are currently and have been for a long time,” he says, referring to government funding, both provincial and federal.

“If we broaden that base a little bit more, we can end up doing more innovative kinds of programming and service delivery.”

In the meantime, Chittock says AIDS Vancouver still plays an important role in the gay community.

“We’re still a major first stop point of entry for anyone that’s diagnosed with HIV,” he says. “So, if they’re gay, definitely, they’re welcome to walk in our doors and we’ll initiate the service-delivery component within the whole health system, not just within AIDS Vancouver.”

AIDS Vancouver

30th anniversary celebration

Tues, July 30, 6:30pm

The Commodore Ballroom

868 Granville St

Entrance by donation

RSVP required at

3030.aidsvancouver.org

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra