Credit: Destination Halifax/J Kimber

When Alan Beck started to sell maps 40 years ago, Canada was the obvious getaway for a gay New Yorker. That’s why he likes it here. And that’s why he flew across the continent to launch his company’s new interactive gay travel website, surrounded by the most enterprising minds of Vancouver’s gay tourist industry.

Beck could have launched Gayosphere from his FunMaps offices in New Jersey, but he chose Vancouver instead.

“I have a soft spot in my heart for Canada,” he says, gesturing with a champagne flute. He has been in the business for 30 years and still thinks of Canada as a more open and welcoming country — a natural gay tourist destination.

But times have changed. In the past five years, Canada has seen far fewer gay travellers visiting from the United States. In 2008, Community Marketing Inc, a San Francisco gay travel research firm, reported that 27 percent of its self-selected pool of gay travellers had visited Canada in the past year. Since then, that number has dropped by half, even though overall tourism has slipped by only 10 percent.

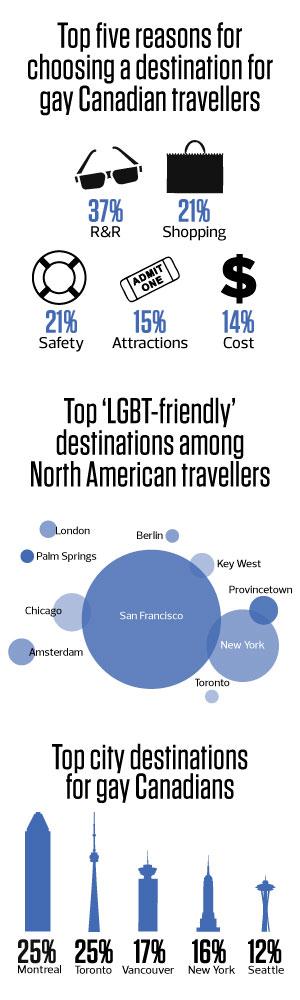

Vancouver has fared even worse. From 2006 to 2008, Community Marketing’s research showed Vancouver to be the most popular gay destination in Canada for American travellers, leading Toronto and Montreal by a small margin. In the last two years, Vancouver has fallen to third place.

And there are other small warning signs. Among both American and Canadian travellers, Vancouver lags behind Montreal and Toronto as a city with a “gay-friendly reputation” — a vital measure of strength in the gay tourism industry.

Gay and straight tourism are both, of course, suffering from a strong Canadian dollar and a weak American economy. But while the general market is slowly rebounding, the gay market is not. If Vancouver is going to retain its place as the gay destination that Beck remembers, it will have to fight for it.

To understand how the Canadian gay tourism market has changed, you will have to go back to 2006. The Olympics in Vancouver were still several years away. The Canadian dollar was worth 90 cents US and hadn’t reached parity in three decades. Canada was still flushed with the passage of the Civil Marriage Act, establishing gay marriage in federal law. Meanwhile, same-sex marriage was only a dream in Mexico, Argentina and Washington State. And most importantly, the recession had not yet stripped the world’s travellers of their disposable incomes.

Then, in 2007, the Canadian Tourism Commission decided to shift strategies for promoting Canada. Under the new system, they target what they call “psychographic” profiles — groups of travellers who are motivated by a particular objective, such as culture, adventure or luxury. Programs targeting specific demographics, including gay people, were phased out.

Quinn Newcomb, strategy management director for the commission, says that the new system is better at targeting the specific desires of groups — such as skiers or seniors — who were once lumped together. Gay travellers, however, are a slightly different bunch. Community Marketing and Travel Gay Canada research has shown that gay travellers don’t just care about the destination; they care whether the destination cares about them. Gay advertising matters because it signals a welcoming culture.

While Canada was shifting focus away from gay travellers, many other countries were getting on board. The legalization of same-sex unions was followed by strong gay tourism efforts in Nepal, Sweden, Brazil, Argentina and Mexico. Even before same-sex unions were legal in Argentina, the Argentine government had set up a national gay chamber of commerce and hosted a gay tourism conference.

With international competition heating up and the Canadian government stepping away from gay tourism promotion, cities and provinces were left to pick up the slack. Some have fared better than others.

In 2009, Vancouver Tourism — funded largely by hotel room surcharges — found its budget depleted by the recession. Facing the Olympics the following year, they cut their niche marketing budget, including gay marketing, entirely. Their marketing communications budget swooped downward, climbing back to 2007 levels only this year. While Tourism Vancouver’s gay promotion budget has returned, it stands at only $70,000. That’s one seventh of Montreal’s budget and only slightly higher than Halifax’s, a city about one sixth the size of greater Vancouver.

“It is a big portion of our consumer direct budget, but it’s also a lean budget,” says Candice Gibson, Tourism Vancouver’s manager in charge of gay marketing. “So much depends on what kind of budget that I have to work with every year. We would love to be in Washington, DC; we would love to be in several cities in Florida and the Northwest. That’s an objective. It will take us some time to get there.”

Rick Hurlbut, a travel agent and 20-year veteran of the gay tourism industry, says that the brief history of gay travel is littered with destinations — from Amsterdam to San Francisco — that thought they were safe, only to see guests go elsewhere. And while Vancouver is recovering, other cities are charging ahead.

With a weighty $500,000 budget for gay tourism advertising, Tourism Montreal not only buys ad space, but also actively funds the local gay community to create friendly events and attractions.

“It’s important that we work closely with our local community, because they are the ones who create the community which people are going to see when they’re here,” says Tanya Churchmuch, who manages gay promotions for Tourism Montreal. “We can’t have a really insular gay community and then tell the world to come and visit. They’re going to be disappointed.”

Halifax has also made a name for itself, energetically advertising to gay cruise ships and conferences. Destination Halifax, the local tourism agency, boasts a 2010 Summit International award for LGBT marketing on an annual budget of $65,000.

Lynne Ledwidge, who manages gay tourism promotion for Destination Halifax, says that she succeeded by acting quickly and paying organizations like Travel Gay Canada and Community Marketing for vital consumer intelligence. “We actually did something about it quickly and properly,” she says. “We’re a small city without a large advertising budget, but if we build relationships with people who are influencers, that’s the magic for us.”

Spending in Toronto is more difficult to track, since Tourism Toronto does not have a dedicated gay and lesbian budget. But a broad marketing campaign, an impeccable international gay reputation, video promotions for its annual Pride parade, and an aggressive and successful lobby for WorldPride 2014 all show a city dedicated to the gay market.

“It’s an organizational priority. It’s not just one person’s responsibility,” says Andrew Weir, vice-president of communications at Tourism Toronto. He says that marketing to gay travellers is a priority because a gay market is a sign of a thriving tourist industry. “Cities that are perceived as hot gay travel destinations are perceived as sophisticated, fun, cosmopolitan travel destinations. To be viewed as a desirable destination for gay travellers is absolutely a positive association for Toronto and something we will shout from the rooftops at any opportunity we get.”

So what does Vancouver have to do to burnish its reputation and bring back gay tourists?

Aside from simply sinking more money into advertising, Vancouver may also have to take a cue from Montreal and help to foster more gay cultural events. Angus Praught, who runs Gayvan.com Travel Marketing, says that Vancouver needs a big gay event in addition to Pride, like Mardi Gras in Rio de Janeiro or the Folsom Fair in San Francisco.

Hurlbut agrees. “Honestly, the thing that we need to be doing isn’t messaging; it’s creating,” he says. “Our tourism bureau, our city, our province, they become an incubator for new ideas. Yes, we’ve got a Pride parade; yes, we’ve got WinterPride, but if we had something new, we could sell it.” The trouble, he says, is the financial risk in funding any large new event.

On the other hand, as gay people feel more comfortable travelling to more destinations, gay travel advertising may also have to focus less on traditional gay activities like partying and more on conventional tourist activities with a gay-friendly touch. That’s how Halifax has succeeded despite its small gay community.

“A gay traveller isn’t looking for everything gay,” Churchmuch says. “All they are looking for is being able to have a good time and feel like they will be welcomed for who they are.”

Whichever course Vancouver takes, Hurlbut thinks that the only way to retain gay travellers is to keep an eye on the rapidly changing gay market.

“As the nature of gay rights and the gay community continue to evolve, so will every other aspect, including travel and tourism,” he says. “We used to be happy to go to Fire Island and nowhere else because there were so few choices. Now we have so much choice that all the traditional gay destinations are having to think about how to hold on to their traditional client base.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra